For people interested in open science, Paul David& #39;s paper is, I think, the best piece ever written about how science came to be as open as it is: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2209188>">https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/pape...

Odd, actually. This - open disclosure and spread of scientific knowledge - is one of the most extraordinary and important institutional innovations in human history. It& #39;s like... democracy, or law, or [etc] in impact. But much, much less remarked upon.

May as well add: Mary Boas Hall& #39;s biography of Henry Oldenburg is a wonderful, more personal account that is wrapped up with the origins of open science. https://amazon.com/Henry-Oldenburg-Shaping-Royal-Society-ebook/dp/B0029ZA4OQ/ref=sr_1_fkmr1_1?keywords=mary+boas+hall+oldenburg&qid=1574283531&sr=8-1-fkmr1">https://amazon.com/Henry-Old... (Yeah, that price. I read a library version - then shelled out for my own copy.)

And Elinor Ostrom& #39;s "Governing the Commons" - my most-frequently bought book, I believe - is a wonderful book about setting up functioning commons. Not directly open science, but very relevant: https://www.amazon.com/Governing-Commons-Evolution-Institutions-Collective/dp/1107569788/ref=dp_ob_title_bk">https://www.amazon.com/Governing...

One of my most beloved WhatsApp chat groups has St. Elinor as its icon  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">

The fact scientists _rush to disclose_ much of what they know is absolutely astonishing, when you think about it. We take it for granted, but it& #39;s a very carefully constructed state of affairs that required a lot of work: https://twitter.com/michael_nielsen/status/1197247897038774272">https://twitter.com/michael_n...

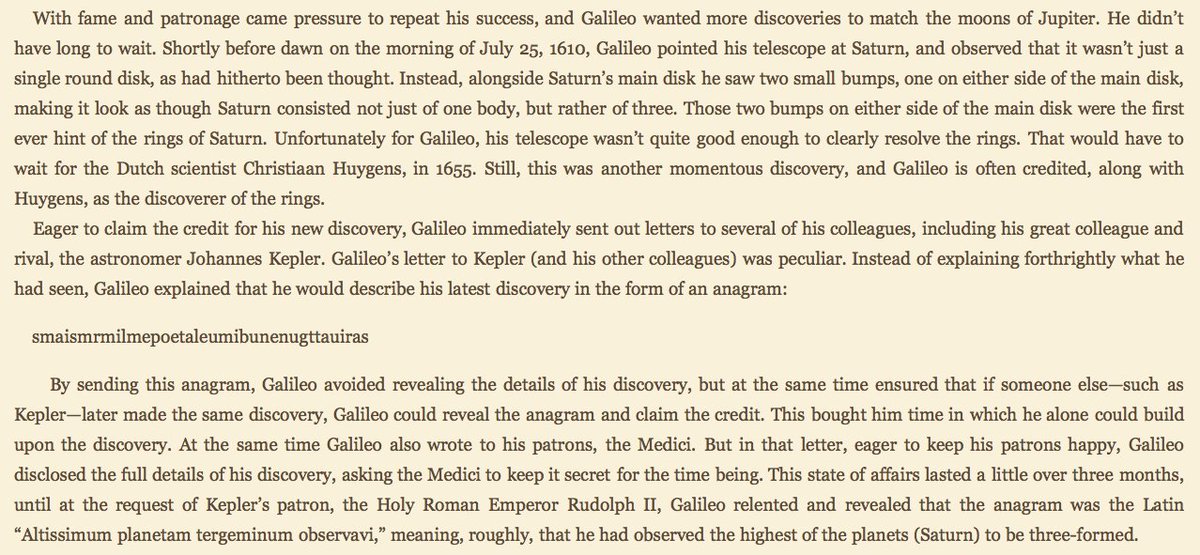

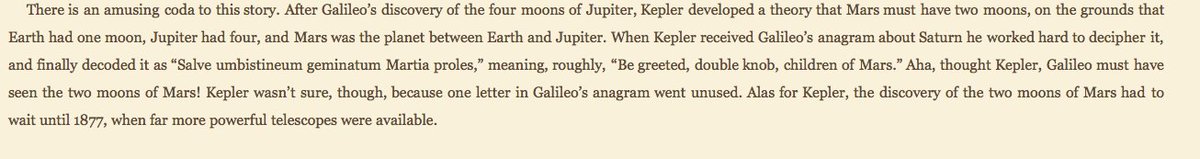

Prior to journals, scientists like Galileo would publish discoveries as... anagrams! So they could reveal nothing, but if someone else later made the discovery, they& #39;d claim priority.

And you thought closed-access journals were bad .

And you thought closed-access journals were bad .

In fact, Galileo may have done this because he& #39;d had a book experience with stolen work when younger - no priority system!

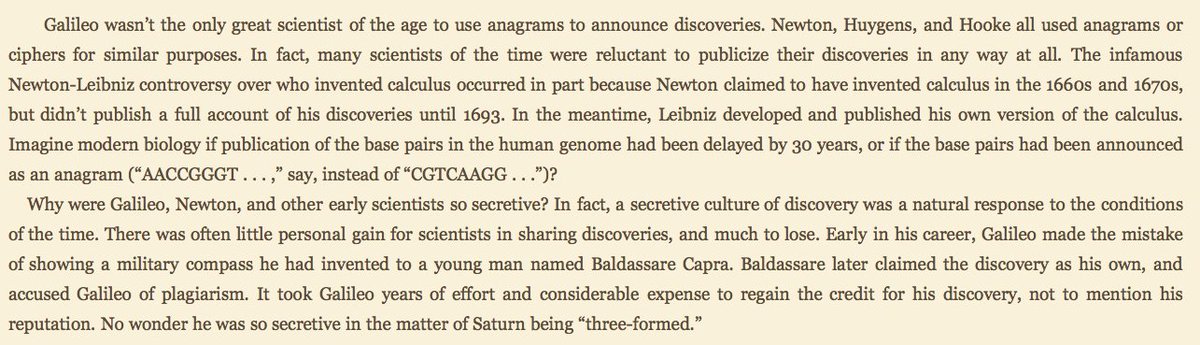

The early journal editors had a terrible time getting anyone to publish. Why on earth would you reveal what you know? Mary Boas Hall, biographer of the first journal editor, Henry Oldenburg, has a bunch of stories about the stuff he got up to to do this.

I don& #39;t have the details in screenshottable form. But, IIRC (it& #39;s been ten years!), she makes a case that part of the reason for the Newton-Leibniz row was because Oldenburg was provoking each to disclose more and more about calculus, playing them off each other.

He was very skilled at managing such interactions, playing traffic cop at the intersection. But he died partway through such an interaction, and this caused a breakdown in communications. (I& #39;m pretty sure I have some details wrong here, and can& #39;t easily check, but the gist right)

The people enabling open scientific data, open code, etc, today are in much the same spot as Oldenburg. It& #39;s challenging, a bit fraught, & requires much ingenuity. And will be looked on very kindly by history!

Postscript: Back around 2008 I saw a piece by Robert Boyle (IIRC) that introduced the term "open science". I thought "oh, cute, I should look at that in detail". Didn& #39;t follow up immediately and later... I couldn& #39;t find it! I& #39;ve been looking ever since. Anyone have leads?

The obvious suspicion: I& #39;m misremembering who it was, or the type of source it was. My memory is it was something short-ish by Boyle. But maybe it was someone else?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="One of my most beloved WhatsApp chat groups has St. Elinor as its icon https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="One of my most beloved WhatsApp chat groups has St. Elinor as its icon https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😃" title="Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund" aria-label="Emoji: Lächelndes Gesicht mit geöffnetem Mund">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>