Thread:

If you had 55 minutes to tell the 200-yr story of your state’s Supreme Court, would you devote 8% of it to profiling a judge who ruled that the renter of a slave must have the power to shoot her in the back as she runs from a brutal beating?

If you had 55 minutes to tell the 200-yr story of your state’s Supreme Court, would you devote 8% of it to profiling a judge who ruled that the renter of a slave must have the power to shoot her in the back as she runs from a brutal beating?

To be more precise: would you use that time to argue that the judge was “one of the ten most influential common-law judges in American history,” an “important figure” who was “one of the truly great judges of his time, state and federal?”

That’s what @publicmedianc (UNC TV) did in broadcasting “N.C. Supreme Court at 200–Stability and Change–1819-2019” a few days ago. This thread will be long, but it will leave you wondering what on earth they were thinking-why they decided to rehabilitate this judge& #39;s reputation.

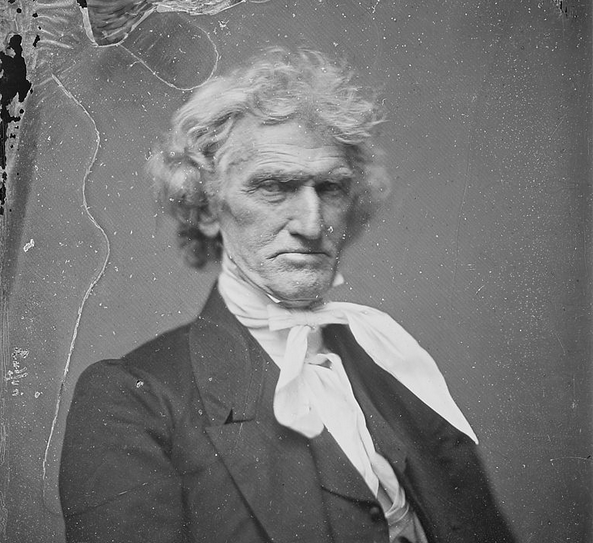

The judge in question was Thomas Ruffin (1787-1870). He was on the NC Supreme Court from 1829 to 1852 and 1858-1859. He served as Chief Justice from 1833 to 1852. He was a brilliant and prolific jurist. No doubt about that.

He’s still kind of a big deal. His nearly life-sized portrait dominates the courtroom of the NC Supreme Court. A life-size statue of him stands outside the NC Court of Appeals. And there’s a dormitory named for him at @UNC.

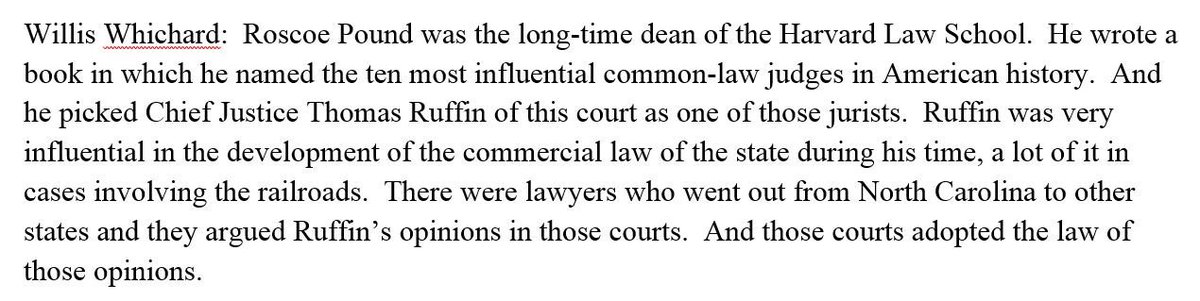

Here’s what the documentary says about him. The first to speak onscreen is Willis Whichard, who served on the NC Supreme Court from 1986 to 1998.

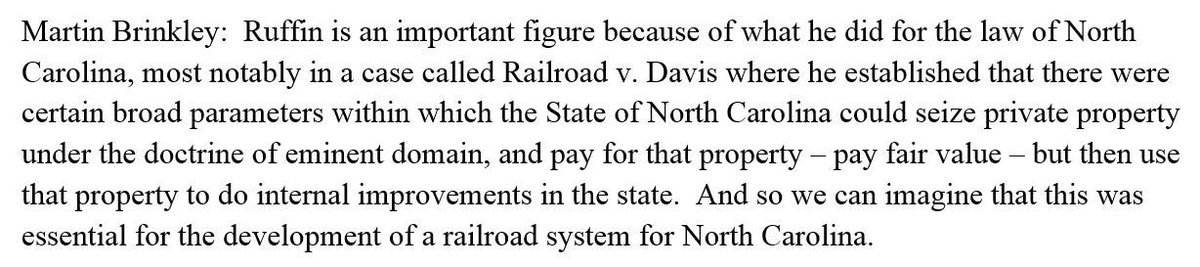

Then comes the dean of my law school, who speaks (quite accurately) about Ruffin’s judicial contributions to the economic development of the state.

The narrator then interjects that though Ruffin “reflected the beliefs of the society around him” on slavery, today we recognize his legal skills and contributions to the law. (Preview: he *didn& #39;t* reflect the beliefs of the society around him--stay tuned)

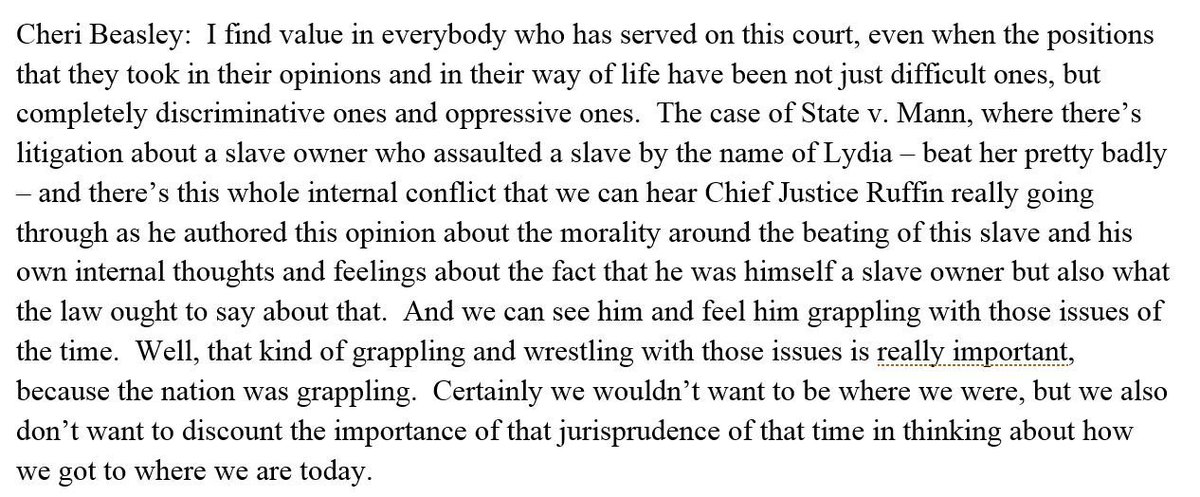

Then comes current Chief Justice Cheri Beasley, who alludes to the facts of State v Mann, Ruffin’s opinion holding that in order for slavery to work, even temporary owners of slaves must have absolute dominion over their bodies. (She doesn& #39;t actually state the holding, though.)

(She says that Mann, the defendant in the case, gave the slave Lydia a beating, but he actually shot and wounded her.)

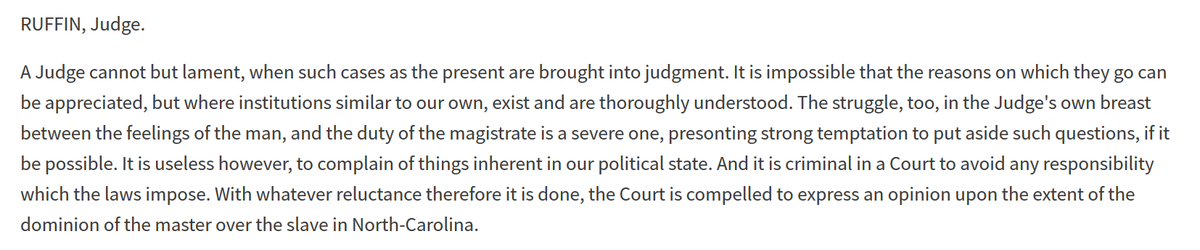

Ruffin wrote how lamentable it was that the law compelled him to rule for Mann rather than Lydia. Chief Justice Beasley credits these “lamentations,” saying his “internal conflict” mirrored the conflicts over slavery in American society.

Finally we hear from James Exum, a retired Chief Justice. He defends the portrait of Ruffin that dominates the courtroom. Our past is past; why feel bad about it? We should instead feel good about our relentless progress we’ve made.

The trouble is that all of this is wrong–contradicted by clear evidence that the tears Ruffin shed in the Mann case were of the crocodile variety. Thomas Ruffin wasn’t “a man of his time” when it came to slavery. He was a man at its ugly fringe.

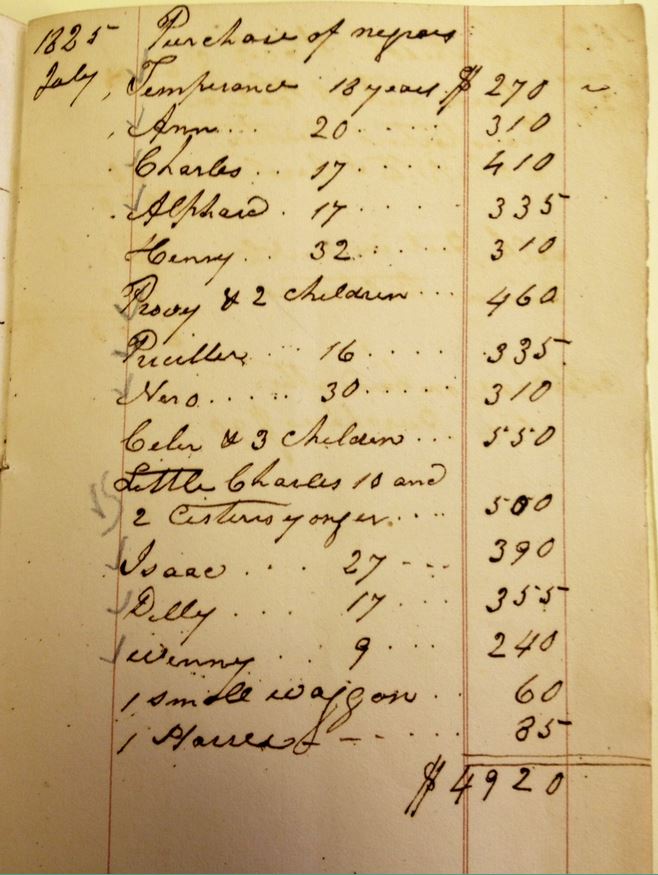

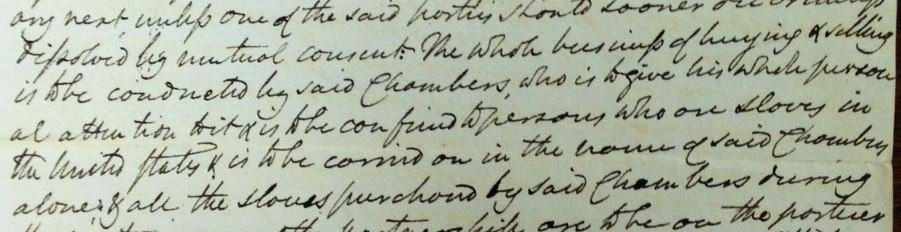

First: Thomas Ruffin was not just a slaveowner. He was a slave *trader*. For years (including while a judge) he ran a trading business with a partner named Chambers. They bought people cheap up north and sold them for a profit down south.

By the time Ruffin entered the industry, slave trading was no longer something honorable people did. And he knew it; that’s surely why the partnership agreement said Chambers would not use Ruffin’s name.

He also knew it was a bad business because peers told him so directly. In 1822 he invited a man to invest in his slave-trading business but the man declined, a main reason being “the trafic itself, against which the feelings of my mind in some measure revolt.”

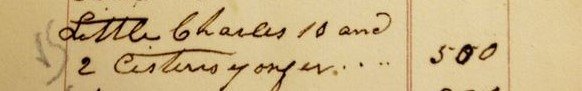

Second, Ruffin routinely sold children away from parents and husbands away from wives (or vice versa). Look at this ledger from the trading business. “Little Charles,” 10 years old, “and 2 cisters younger” were sold for $500. No parent.

(Chambers later sold Little Charles and his sisters in Alabama for $850, earning himself and Ruffin a profit of $350.)

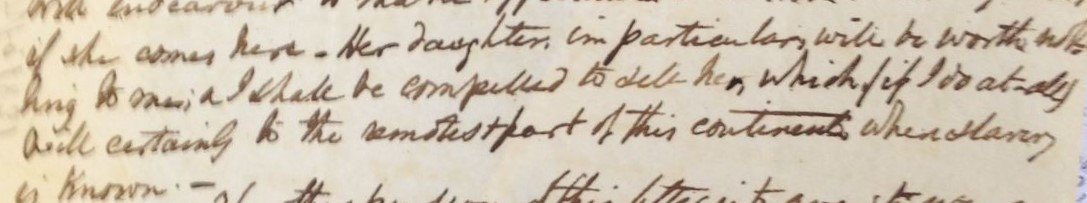

Ruffin also did this to the slaves on his own plantation, people he’d known for a long time. In 1852 a neighbor offered him $150 for a slave named Noah who, with his wife, had been with Ruffin for years.

Ruffin had his daughter to ask Noah how he felt about being sold; she reported back that Noah was “anxious … to spend the remnant of his pilgrimage here on earth in the society of his beloved better half.” Ruffin sold him anyway.

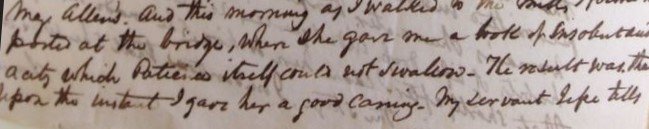

And third, Ruffin was himself a slave batterer. He once owned a slave named Bridget and her daughter. He saw Bridget as a troublemaker and sold her (but not her daughter) to a colleague. He let it be known that he did not want her around.

One day she showed up anyway, to visit her daughter. Ruffin came upon her in the morning by a bridge on his property. She gave him a look he did not like. So he gave her “a good caning.”

State v Mann established that it was lawful for an owner to beat his own slave. But under no scenario was it lawful for a person to beat someone else’s.

Ruffin also told Bridget’s owner that if she returned to his plantation, she would “ruin his slaves,” and he’d have to sell Bridget’s daughter “to the remotest part of the country where slavery is known.”

So Thomas Ruffin was not merely a “man of his time.” In truth, “his time” included a range of views on slavery, and a range of ways white people conducted themselves. Ruffin was decidedly a moral laggard in his generation.

And what of the Mann opinion itself? Ruffin said the law left him no choice but to approve of Mann’s shooting Lydia. But Sally Greene documents in exquisite detail false this is. The outcome of Mann was not compelled; it was his choice. http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4363&context=nclr">https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewc...

The documentary relates none of this, even though it’s all readily available, as, for example, in this article of mine. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4b74/6a39f03661c79224d214679d05c59830ade3.pdf">https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4b74/6a39...

20 or 30 years ago the documentary might have been forgiven for omitting all of this. When Ruffin& #39;s grandson published his grandfather& #39;s "collected papers," he (surprise!) omitted every single document that cast Ruffin in a bad light. So, much of this was not known.

But the historical record has now been complete for over a decade.

Thomas Ruffin no more reflected "the beliefs of the society around him" on slavery than Dick Cheney reflects the beliefs of our own society on torture, or Stephen Miller on immigration.

So we are left with a puzzle. Why would @ncpublicmedia ignore the historical record and throw its weight behind rehabilitating Thomas Ruffin? What were they thinking? @agordonreed @GoSallyGreene @arielagross @marydudziak @ncnaacp @NCCourts

Thomas Ruffin has had well over a century of veneration. It& #39;s (past) time to face the whole truth. Perhaps this thread can help. @Move_Silent_Sam @UNCSouth @ASLHtweets @legalhistory @SlaveryMuseum @NCRMuseum @ProfJeffries @DainaRameyBerry @DrKeffrelynB https://www.newsobserver.com/article220326985.html">https://www.newsobserver.com/article22...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter