Periodic reminder:

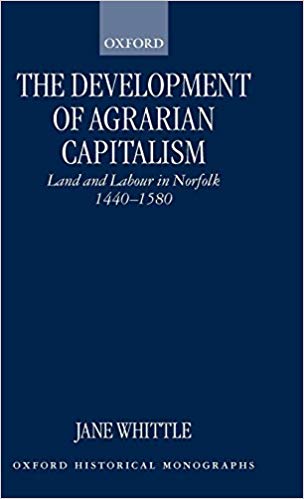

The so-called "Tudor enclosures" of 1450-1550 are considered largely a myth by specialists in English agrarian history.

The so-called "Tudor enclosures" of 1450-1550 are considered largely a myth by specialists in English agrarian history.

Second periodic reminder:

Enclosures ≠ evictions.

Enclosures ≠ evictions.

This. 1000 times this. https://twitter.com/warde_paul/status/1194902089144635392">https://twitter.com/warde_pau...

And this. https://twitter.com/antonhowes/status/1194944021212344320">https://twitter.com/antonhowe...

Most economic historians defer to Allen, who argued that enclosures (in the strict sense of closing off scattered strips of land & often consolidating them into one big plot) were not an important cause of productivity growth in English agriculture, relative to 1500 or to Europe

One of the big dissenters & critics of the Allen view is the agricultural historian Mark Overton, who finds a bigger role for enclosures -- specifically the Parliamentary Enclosures starting in the 18th c -- in making English agric much more productive than before or than Europe

But in terms of the debate over the rise of & #39;agrarian capitalism& #39; in England -- where did all the landless peasants come from who would later become wage labourers? -- then the difference between Allen and Overton is immaterial. They both undermine the Brennerian-Marxist view

IF Allen is right, then commercial agriculture in England emerged & #39;from below& #39;, from & #39;peasant differentiation& #39; by which more successful peasants became became & #39;yeomen& #39;. And England& #39;s agricultural revolution actually started in the 17th century, on both open and closed farms

But IF Overton is right, then most of England& #39;s productivity growth in the period 1500-1850 occurred starting in the 18th century. But then how is it that England saw such a rapid change in occupational structures after 1500? From CAMPOP

(a) There is VERY LITTLE evidence of mass (legal or extralegal) eviction in Eng agriculture -- peasants driven off their land of popular stereotype, as though they were Cherokees in the Trail of Tears. (b) but IF Overton is right that agricultural productivity growth came late...

then the implication of Overton& #39;s view is: this pattern of very precocious structural transformation out of agriculture in England was driven primarily by population growth that occurred after 1500. Simply put: there was not enough land for the extra population.

Note: Jack Goldstone has an argument in the book below that the pattern of landlessness seen in England after 1500 could be entirely explained by population growth; & this arg was made before it was known how EARLY England had achieved such a low share of agricultural employment

So the point is, the Marxist view that landlord action drove peasants off the land through a variety of means legal or extralegal, is not consistent with either Allen or Overton.

Wool & sheep of the Tudor period& #39;s "depopulating enclosures" still have a role in this sense: after the Black Death, which killed app. half the English population, there was left a lot of idle land. Landlords turned much of it into sheep pasture for wool. https://twitter.com/Borners1/status/1194959451310026753">https://twitter.com/Borners1/...

So the conversion of formerly arable land into sheep pasture, motivated by the absence of labour after the Black Death, reduced the available supply of land after England& #39;s population recovery, so & #39;increased& #39; landlessness. But it was not primarily peasants driven off the land!

People keep asking about new crops & other technical determinants of agricultural productivity. But the & #39;agrarian capitalism& #39; debate regarding England is about the & #39;deeper& #39; social causes of the technical productivity advance, esp. whether it was driven by landlords or peasants

This entire thread was motivated by @brankomilan& #39;s blog post in which he observes "In England [peasants] had to be literally chased from land through enclosures [to create landlessness]; but this observation is an aside & NOT important to his overall point https://glineq.blogspot.com/2019/11/the-plight-of-late-industrializers-what.html">https://glineq.blogspot.com/2019/11/t...

Basically he asks how can late industrialisers get the labour necessary for industry, if peasants own the land & don’t want to leave. IMO it’s a good post but the overall point is valid ONLY if peasants are also politically powerful & they use the state to protect agriculture

France, as Branko mentions, was an example where small farmers dominated agriculture AND they were politically powerful. This is similar to Branko& #39;s counterfactual about a democratic Russia without the revolution in which peasants controlled the state through an SR-like party.

But there are too many examples of compatibility of smallholder agriculture & industrialisation -- the US North, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea! but there are many others. Lenin talked about the typology of & #39;Prussian& #39; versus & #39;American& #39; roads to agrarian capitalism:

Yes the most famous the most controversial perhaps the most & #39;classical& #39; kind of enclosure was Parliamentary Enclosures occurring after 1750 & enclosed ~25% of English ag land. BUT in terms of the agrarian capitalism debate, these are VERY LATE developments https://twitter.com/ErikThomson7/status/1194997442409881601">https://twitter.com/ErikThoms...

By 1700 more than half of the English labour force was outside agriculture; this understates the % of wage labour, because many already worked for wages in agriculture. Parliamentary enclosures therefore have no role in explaining the pre-1700 pattern. I post this chart 3rd time

Parliamentary enclosures post-1750 were what E P Thompson made famous as a "plain enough case of class robbery". Much more is known about these than all previous kinds of things which have been called & #39;enclosure& #39;.

Parliamentary enclosures caused many people to lose access to common wood/wastes which were an important source of income for those people. Some smallholders or small tenants were pressured by competition to sell off their land/leases to landlords or large capitalist tenants.

Many (including Allen) have rightly argued parliamentary enclosures caused suffering & made agricultural modernisation more traumatic than necessary.

But evidence for the creation of a substantial landless class from Parliamentary enclosures is LACKING.

But evidence for the creation of a substantial landless class from Parliamentary enclosures is LACKING.

Previous thread on & #39;enclosures& #39; with a more intellectual-history bent (why does the "enclosure myth" persist?) + potted history of enclosure debate + terminology (so many different things are often called & #39;enclosure& #39;) + influence of Polanyi, Chayanov, etc. https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1014879924564430849.html">https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/10...

LAST point. As noted earlier, Allen argues commercial agriculture emerged with the "yeomen& #39;s revolution" in the 17th c. via peasant differentiation. Whittle supports that view for an earlier period; Dimmock gives a full-throttle defence of Brenner& #39;s top-down landlord action

... @EsbenBoegh & @abenanav have complained that I misrepresent Brenner. For the record: I& #39;m addressing all kinds of “enclosure stereotypes”. I& #39;ve never said Brenner reasons as though English peasants were driven from their land like Cherokees, but that is one popular stereotype

Brenner& #39;s reasoning is that lords gained complete control over land; & gradually converted customary long-term tenure to short-term market rent; in this process, only the most commercially successful tenants kept their lands; & many peasants lost theirs: a legal form of eviction

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter