1. “Stretching back to 1968”…?

(a) The Equal pay act was updated because the EEC defended our right to equal pay.

(b) That right was bestowed on us by the EEC before the Equal Pay Act ever came into force.

(c) It goes back a long way before 1968.

(Thread)

(a) The Equal pay act was updated because the EEC defended our right to equal pay.

(b) That right was bestowed on us by the EEC before the Equal Pay Act ever came into force.

(c) It goes back a long way before 1968.

(Thread)

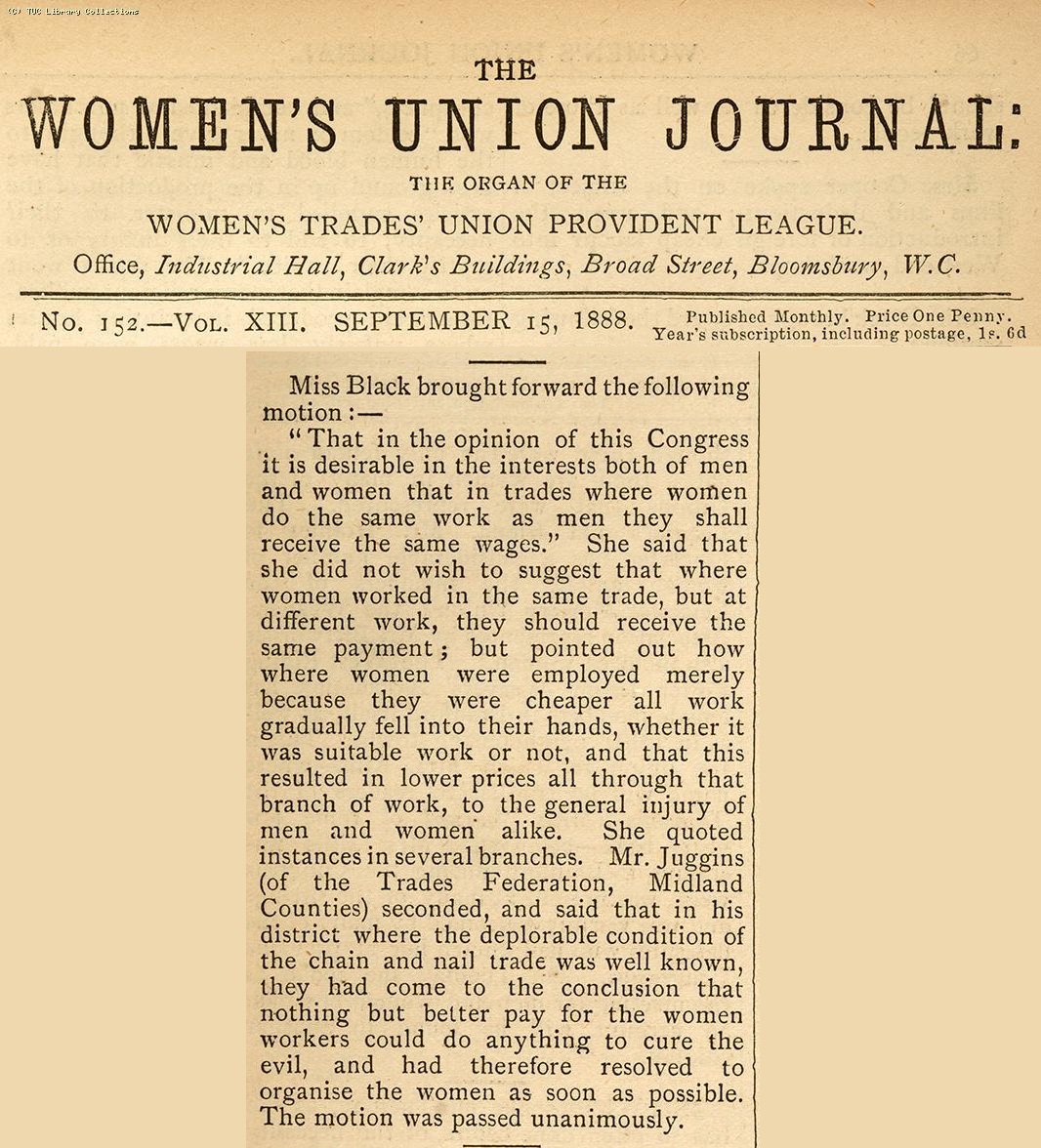

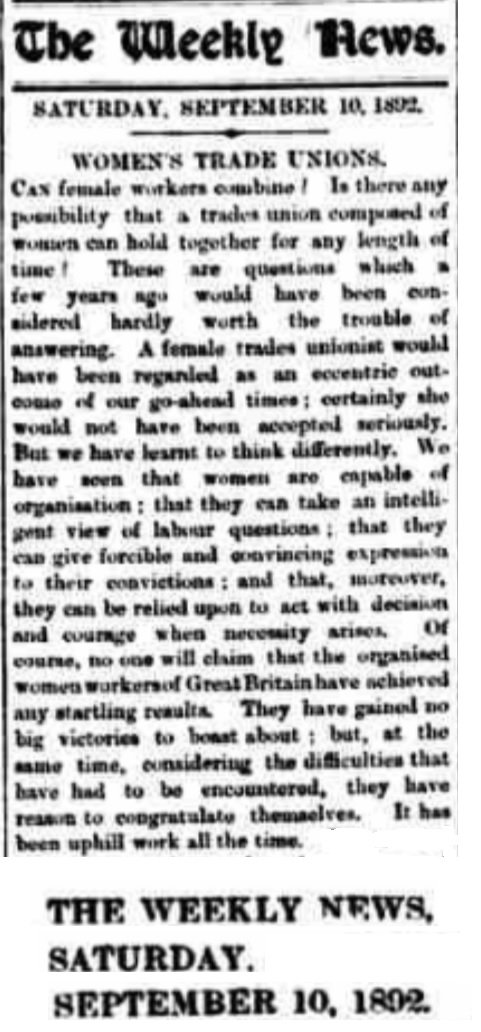

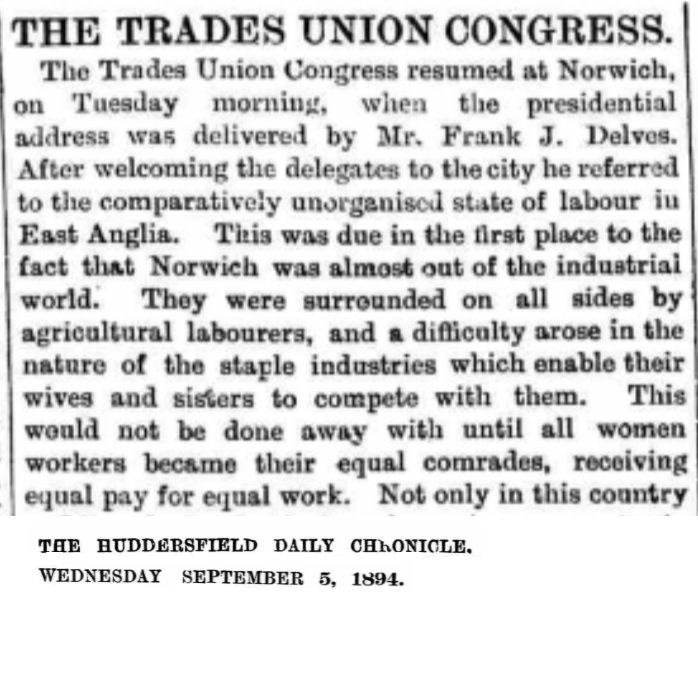

2. It was 1888 when Clementina Black moved the first TUC equal pay resolution, however, the female workforce was small, the unions were male dominated.

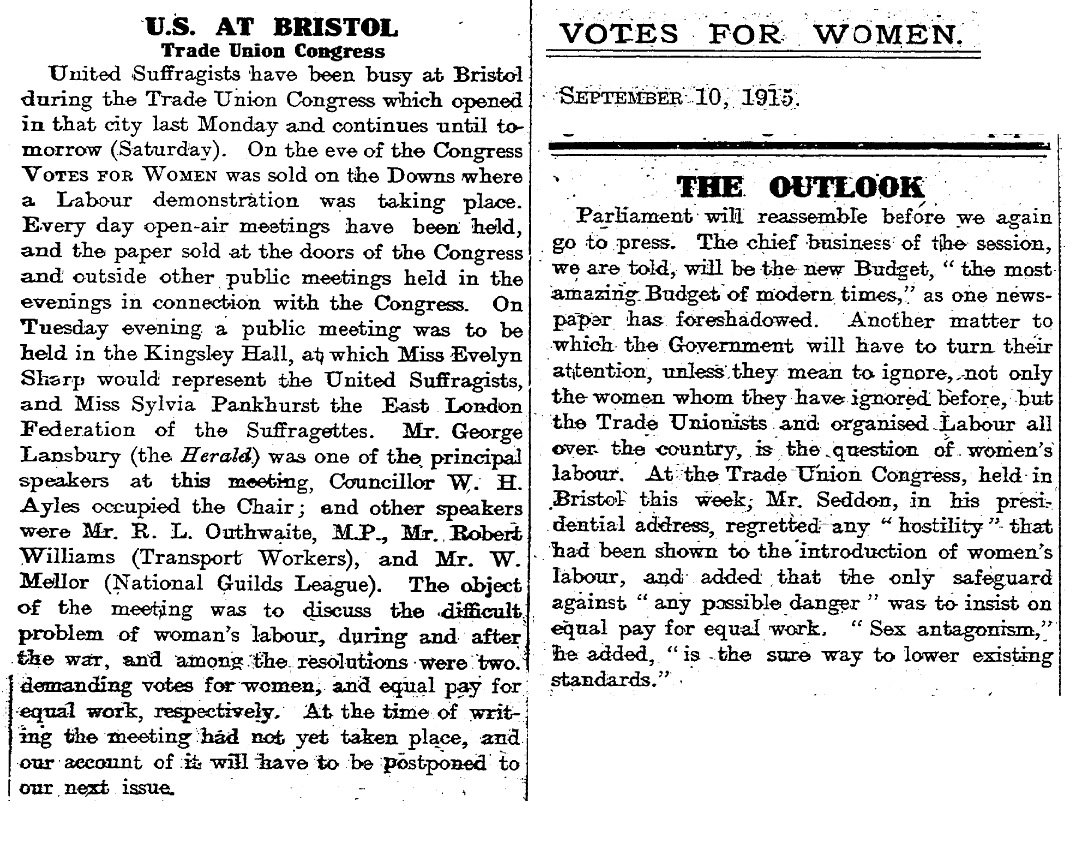

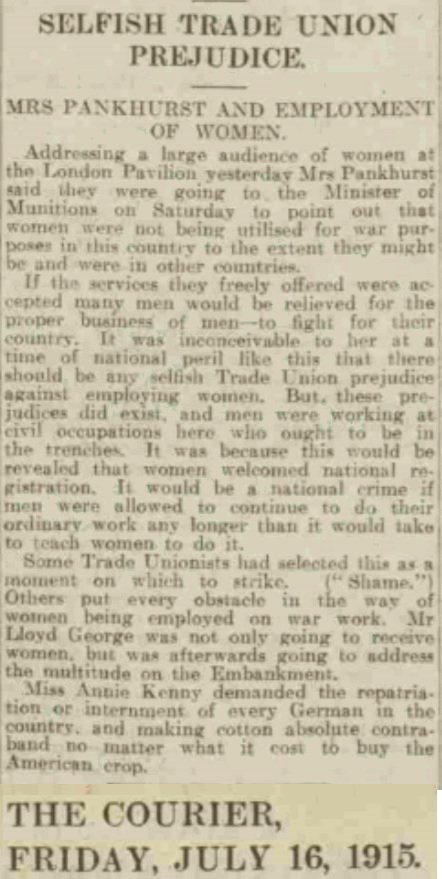

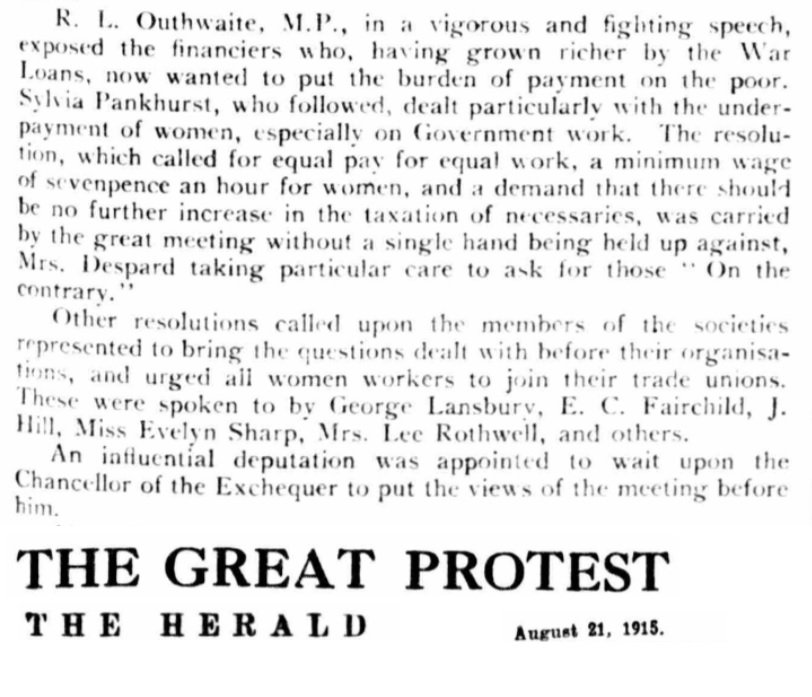

3. The outbreak of the First World War changed this. The suffragist movement encouraged women into the workforce to help the war effort and began to engage with the male unions, although not always constructively...

4. While the war is generally accepted as being a major stepping stone in securing votes for women, it also helped advance the equal pay cause. It wasn& #39;t long before someone proposed a clause in parliament to promote equal pay for teachers.

(Although it lost 93 to 25)

(Although it lost 93 to 25)

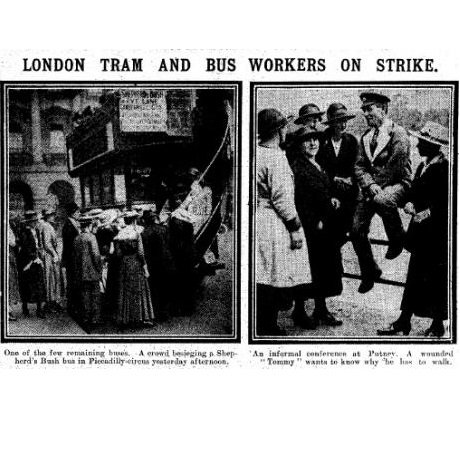

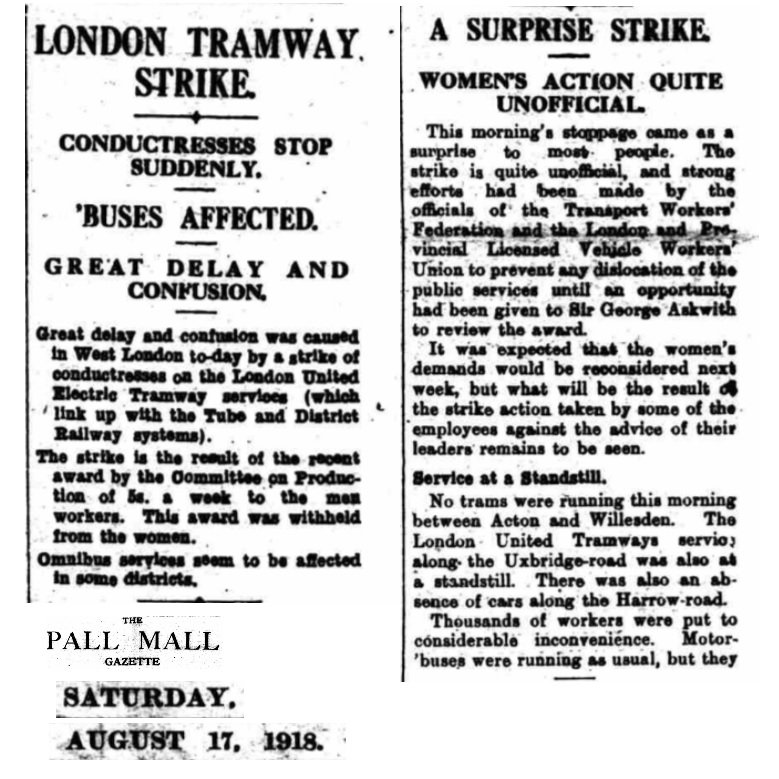

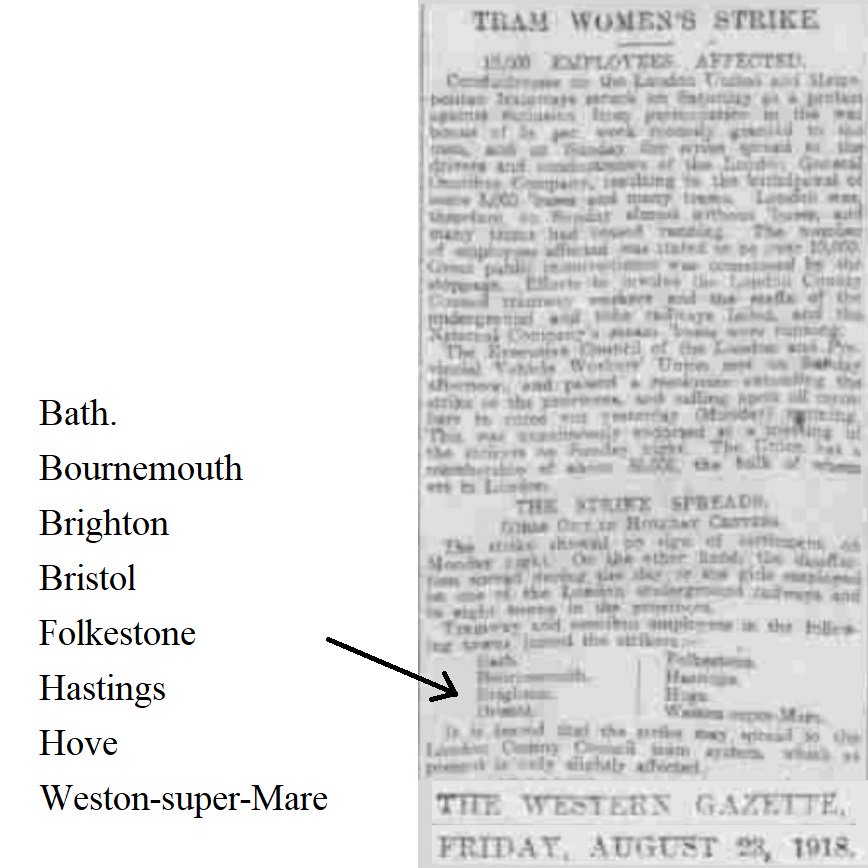

5. And it also created to a female workforce large enough that an argument over a wage increase in a Willesden bus garage could cripple the entire London transport system before spreading around the country.

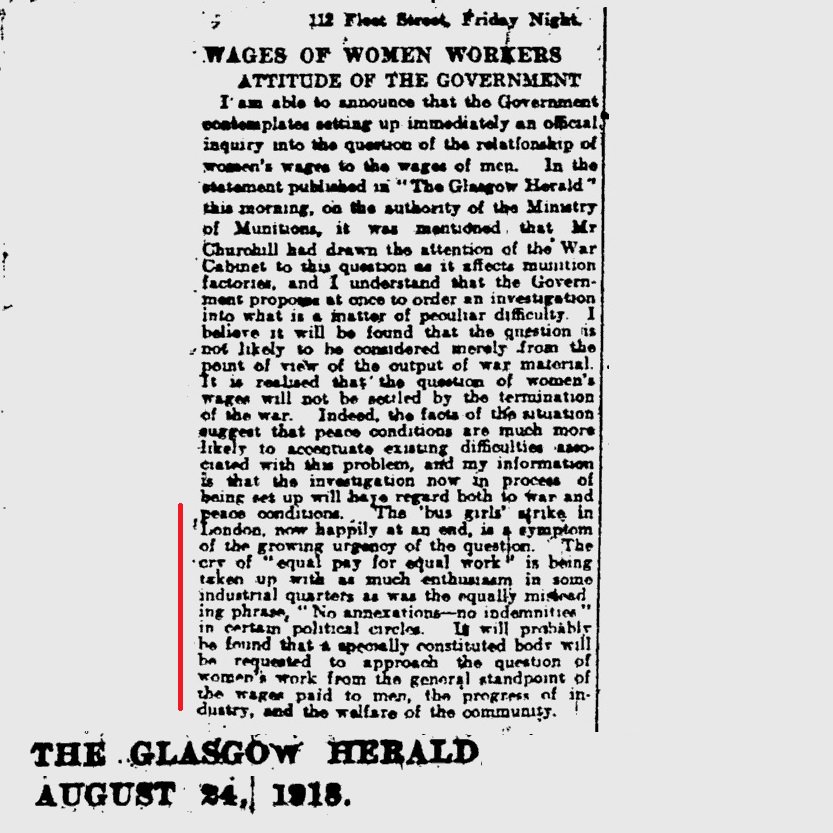

6. For that particular strike, not all the transport strikers got everything they wanted, but the London workers did secure their full wage rise, and questions were already being asked of the government about how they would respond to the increasing call for equal pay.

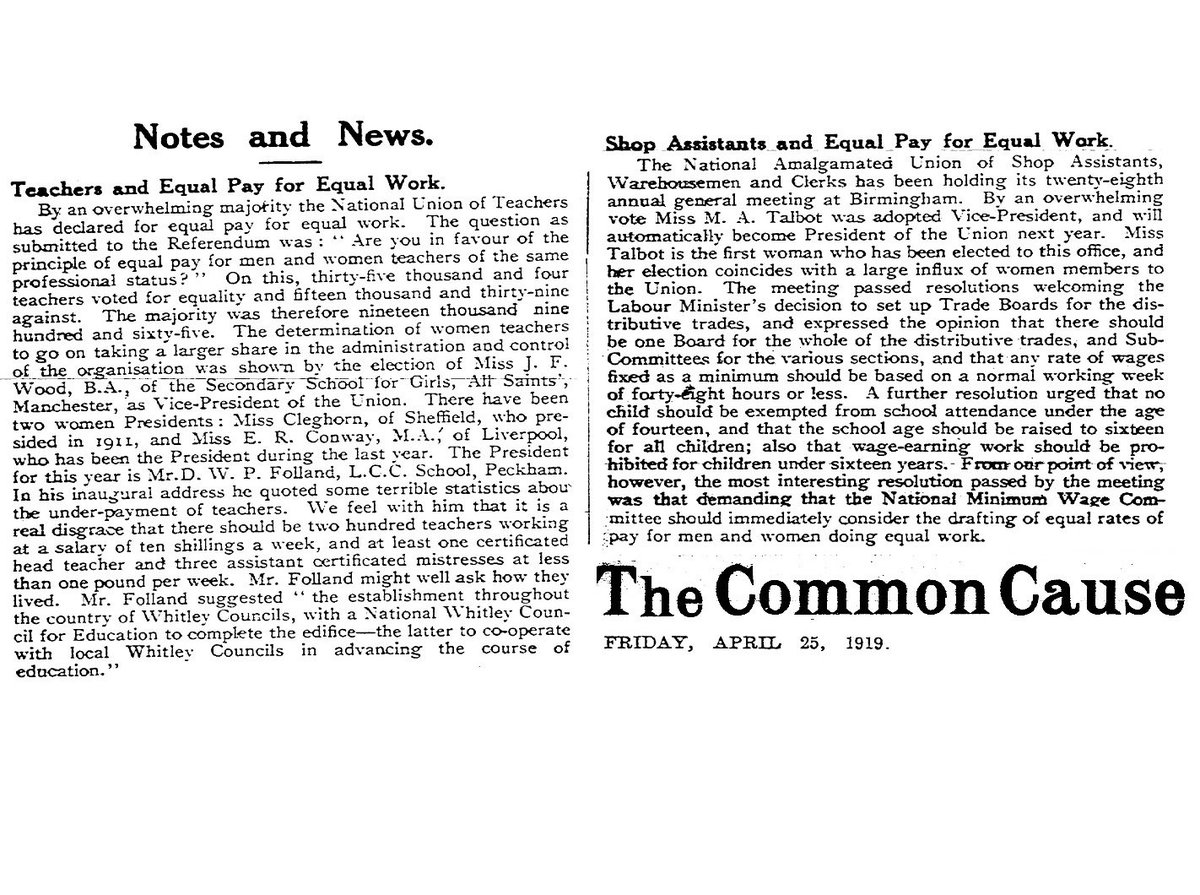

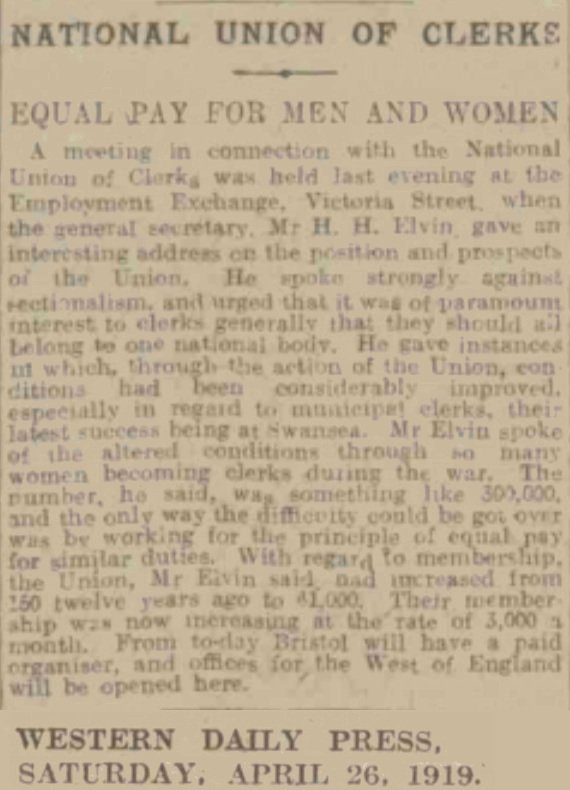

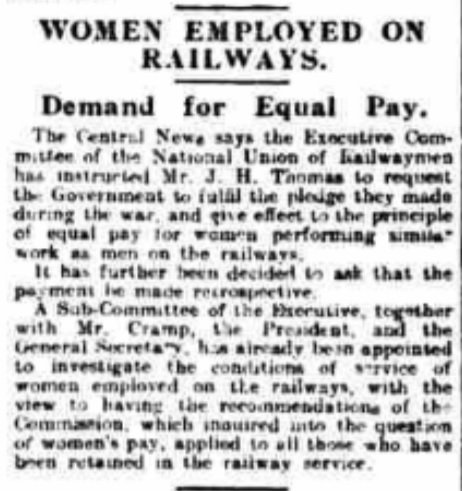

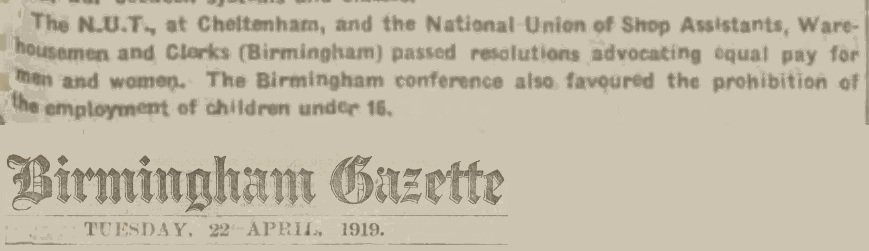

7. A call that continued through 1919 with the National Union of Teachers coming out for equal pay, and unions covering professions such as shop assistants, clerks, railway workers, all pass equal wage resolutions.

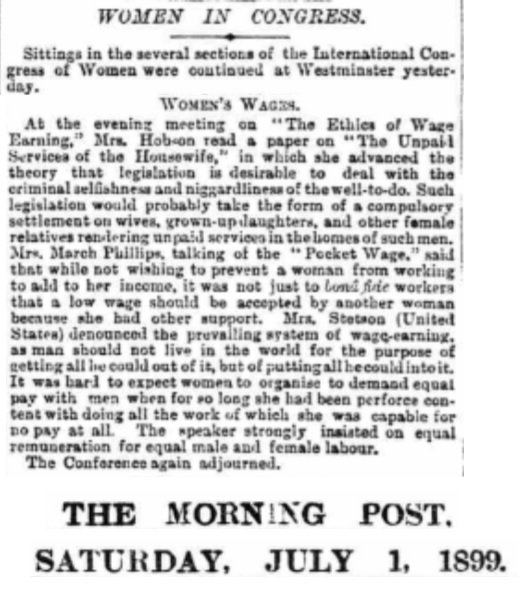

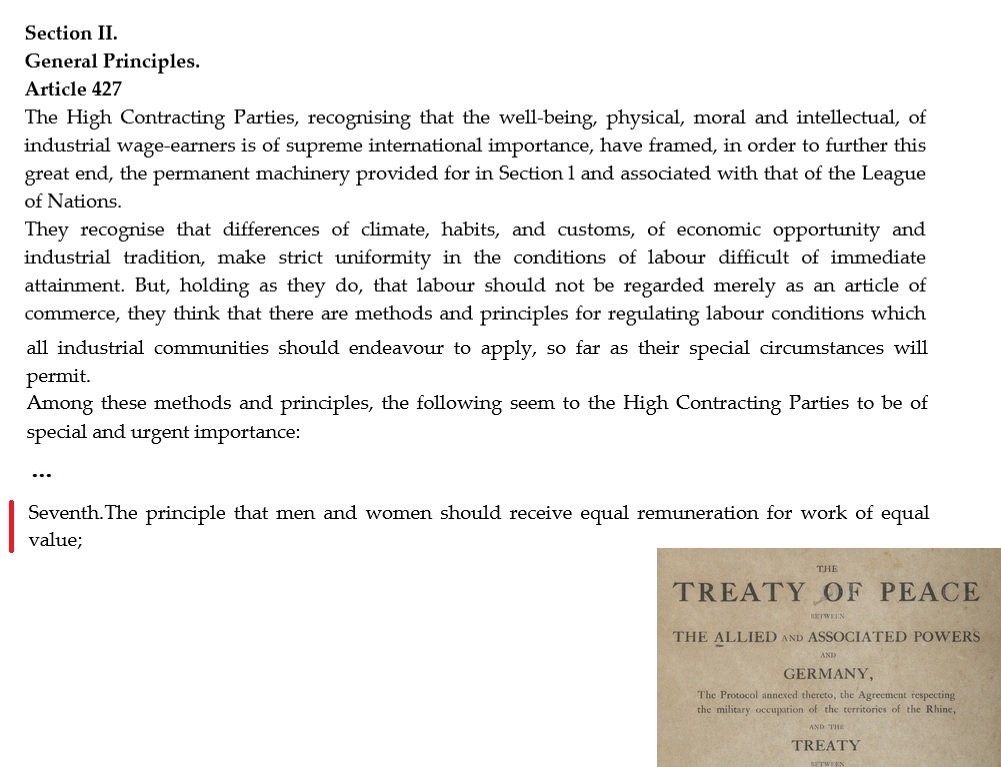

8. This was also the year the UK signed up to the principle that men and women should receive equal remuneration for work of equal value.

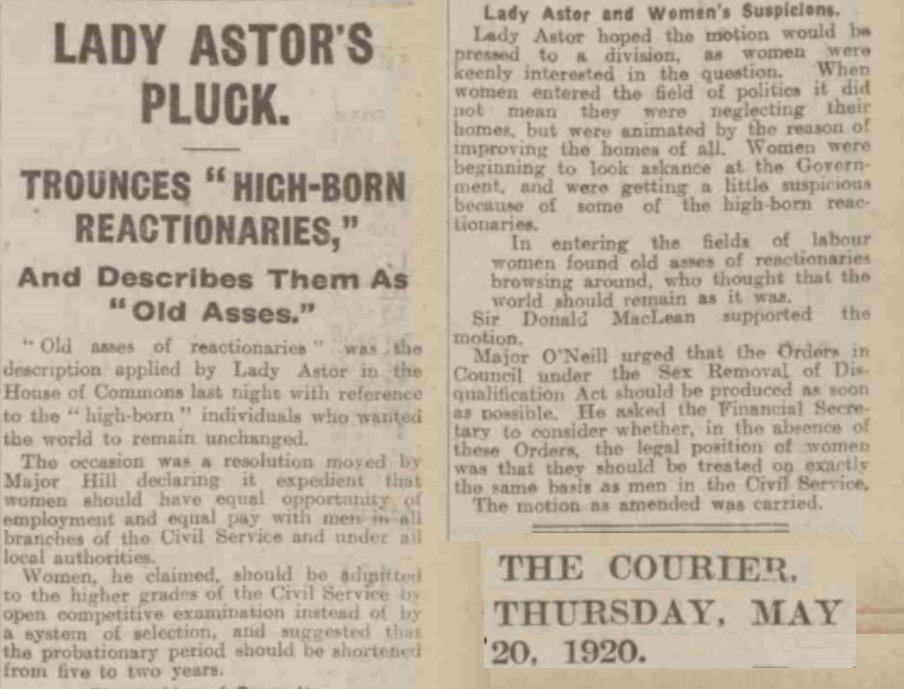

9. And then in 1920, parliament supported a motion in support of equal pay in the civil service, and again in 1921 another motion whereby women’s pay would be reviewed after three years.

10. But the motion comes to nothing.

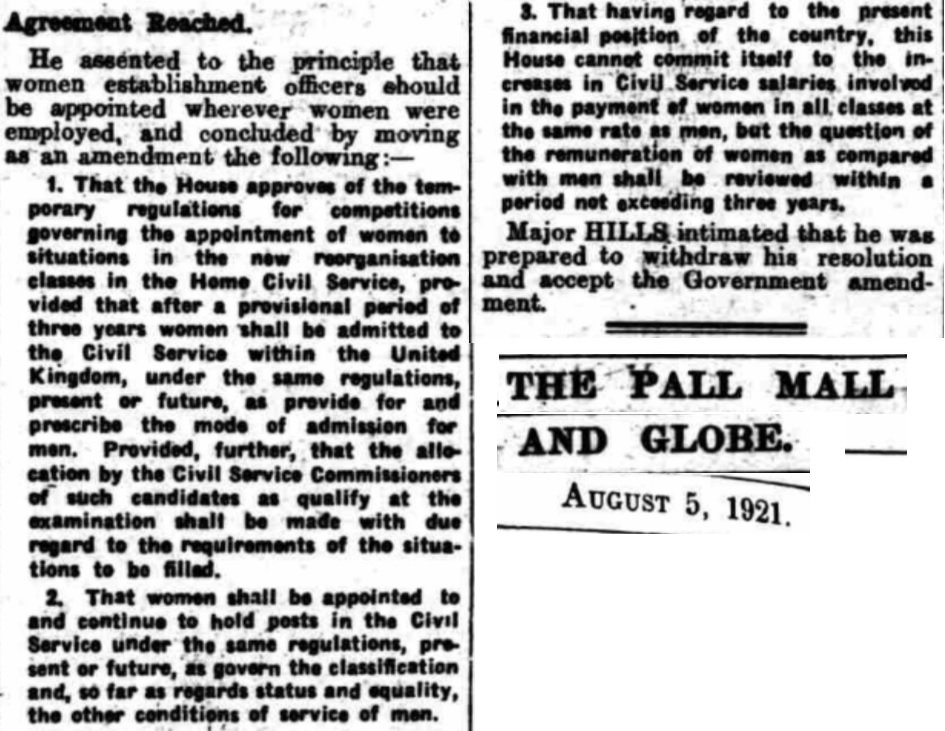

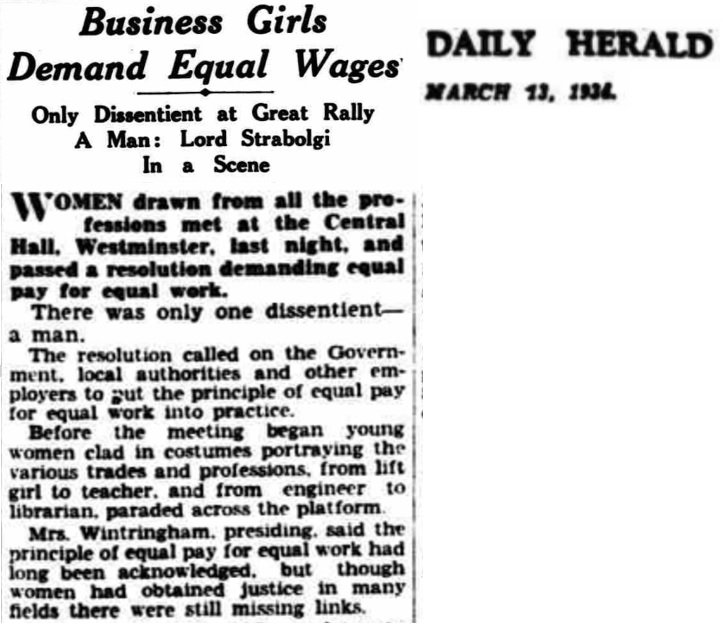

In 1924, parliament is told ‘now is not the right time’, and then again by the next government in 1925, before they repeat the same sentiment again in 1929 using almost identical wording.

In 1924, parliament is told ‘now is not the right time’, and then again by the next government in 1925, before they repeat the same sentiment again in 1929 using almost identical wording.

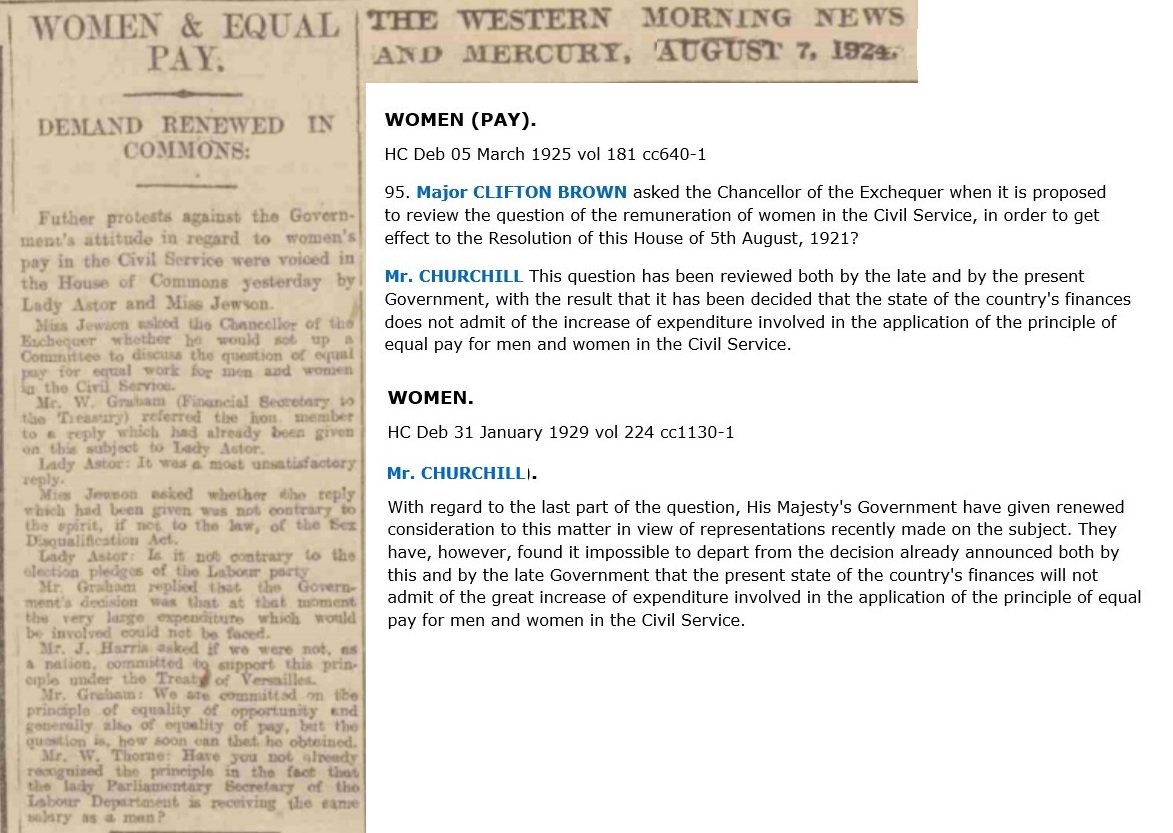

11. The effects of the Great Depression puts equal pay on the back foot, but in 1924, as the economy improved, the London and National Society for Women’s Service and the National Association of Women Civil Servants sought to relaunch the campaign at a meeting in Westminster.

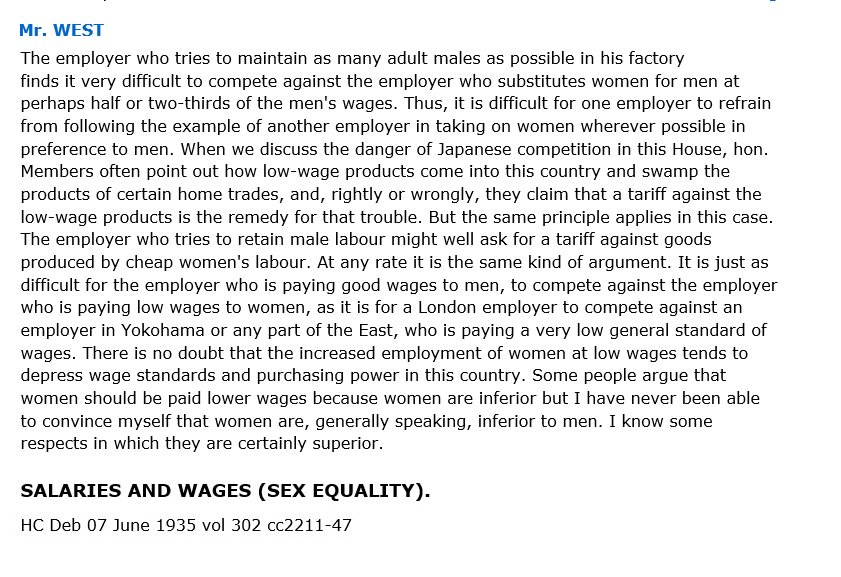

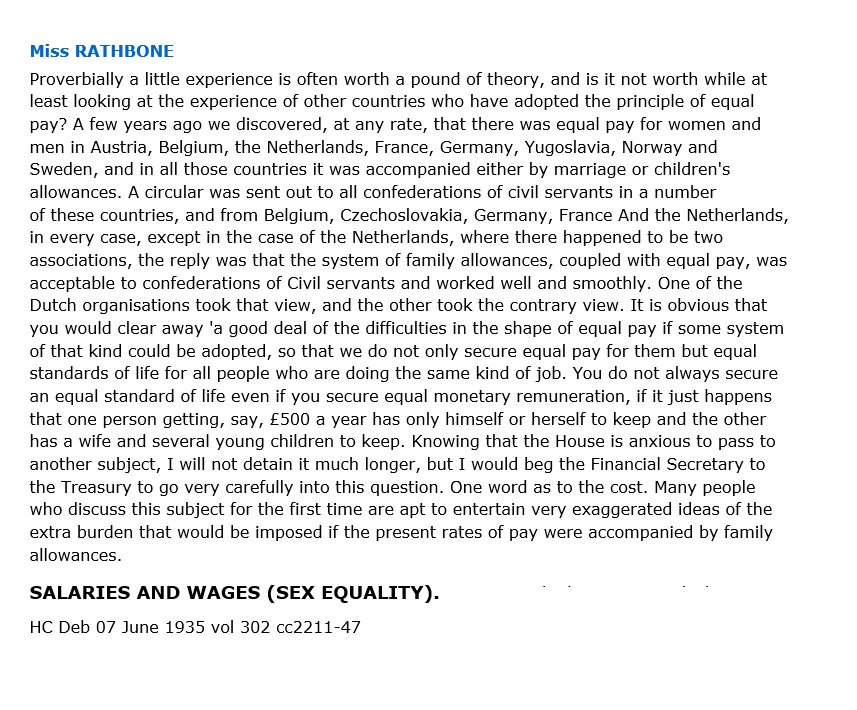

12. This lead to an extraordinary debate in the House of Commons where we see Suffragist Ray Strachey’s modern 1930s argument that wage inequality causes wage depression for men.

13. We then see Eleanor Rathbone, ex-president of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, delivering a Suffragist equal pay argument that derives from the “New Feminism” of the mid-1920s

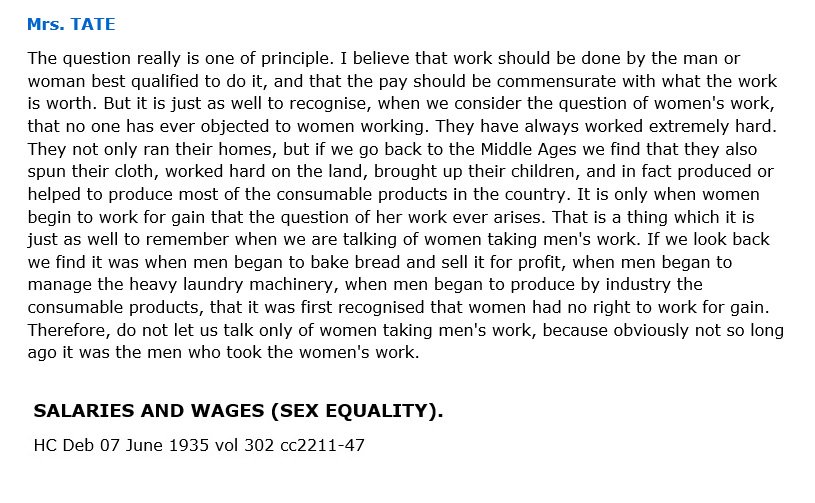

15. In 1936, a private members motion to introduce equal pay in the civil service is put forward and parliament vote ‘Yes’, but then vote ‘No’ on making it a substantive motion, leaving the government to controversially overturn it with a motion of no confidence days later.

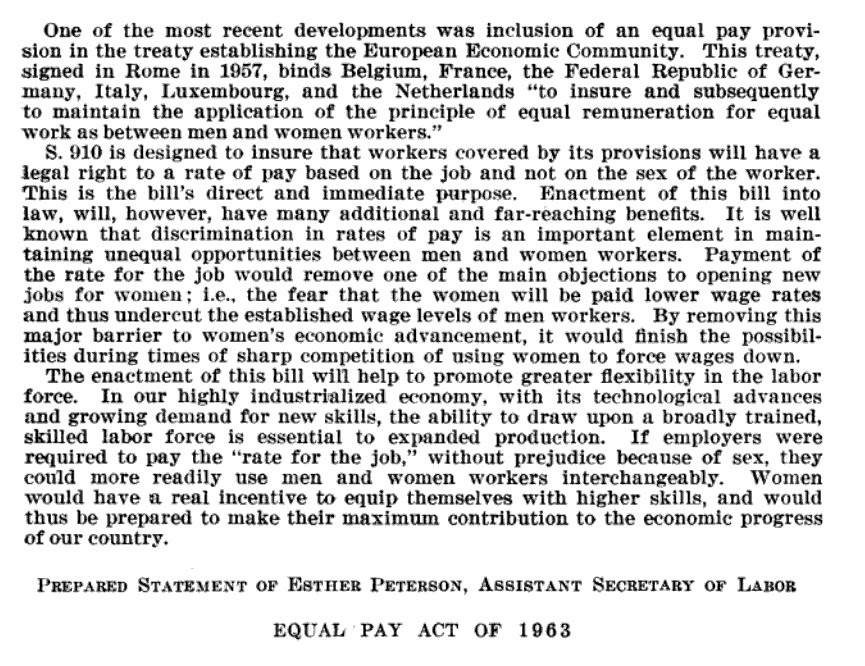

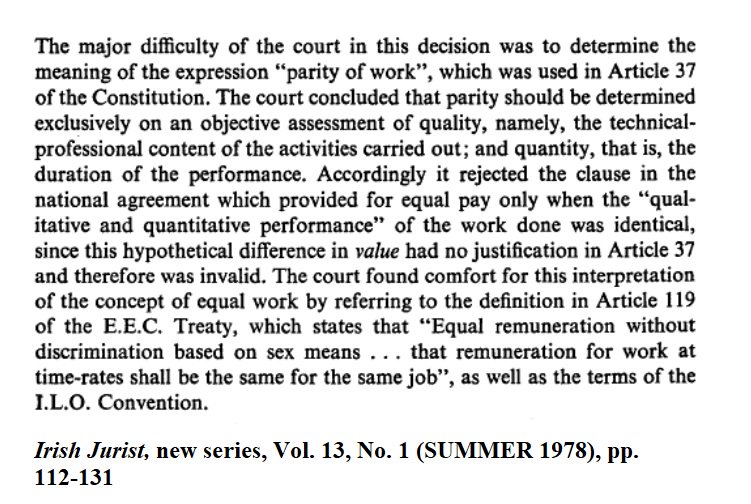

16. Despite the defeat, the Joint Committee on Women in the Civil Service took heart in the initial win, and within a few years there was another war.

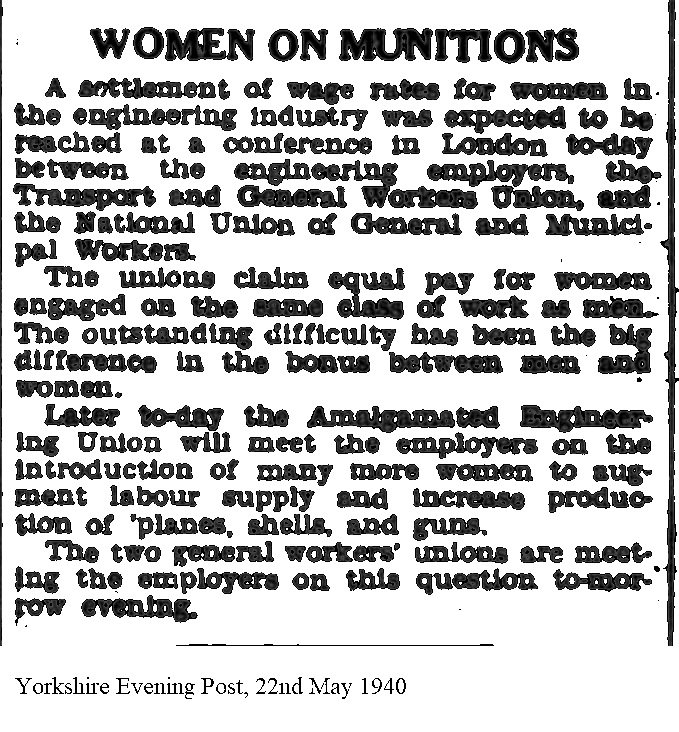

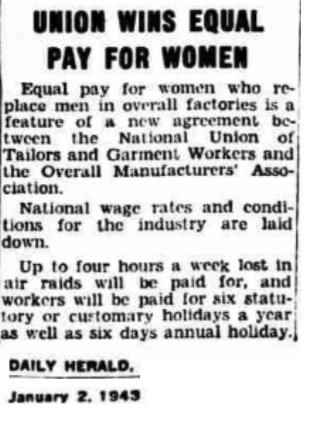

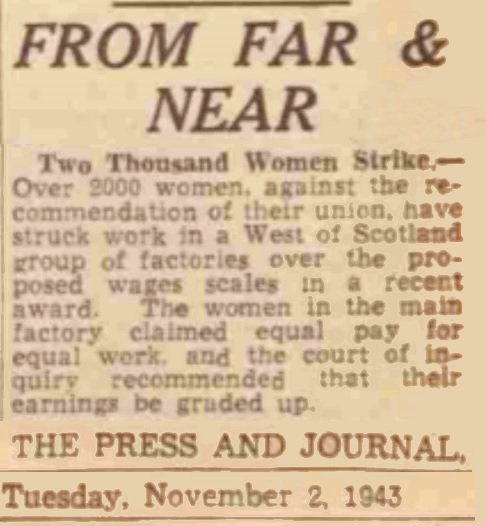

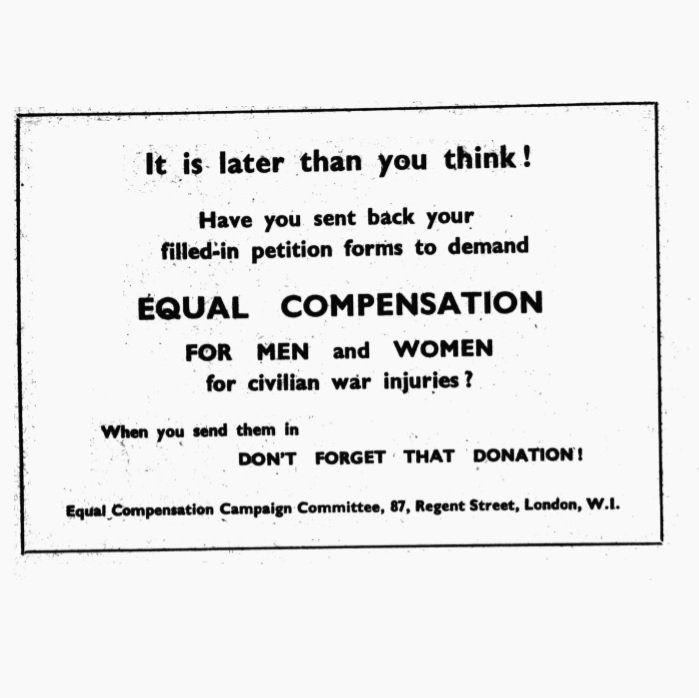

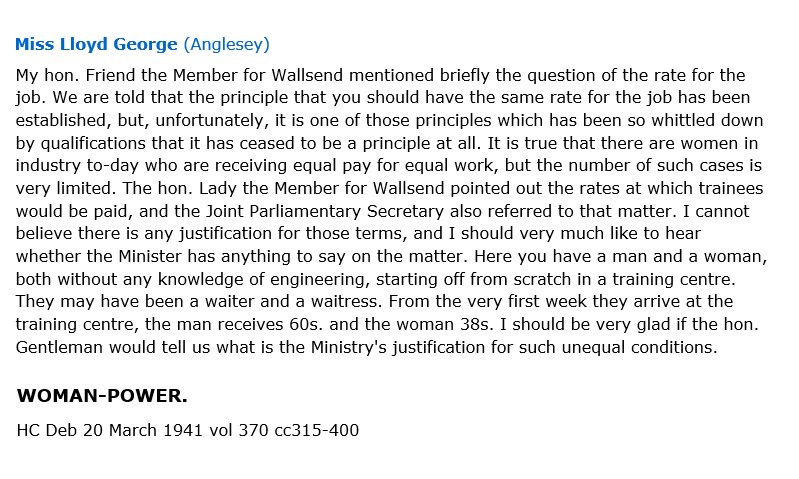

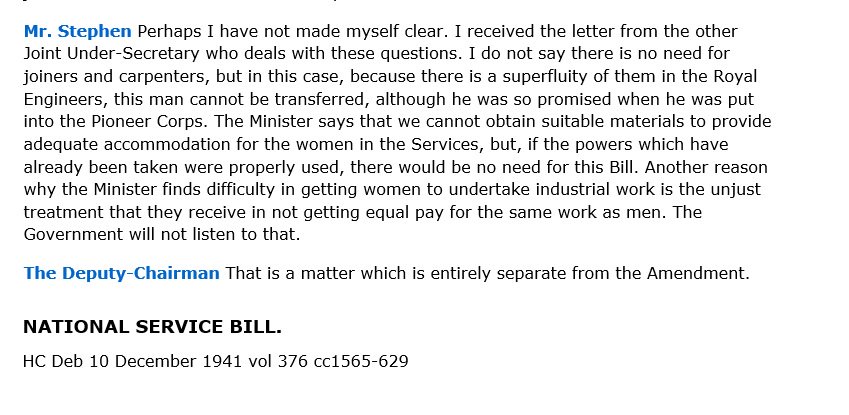

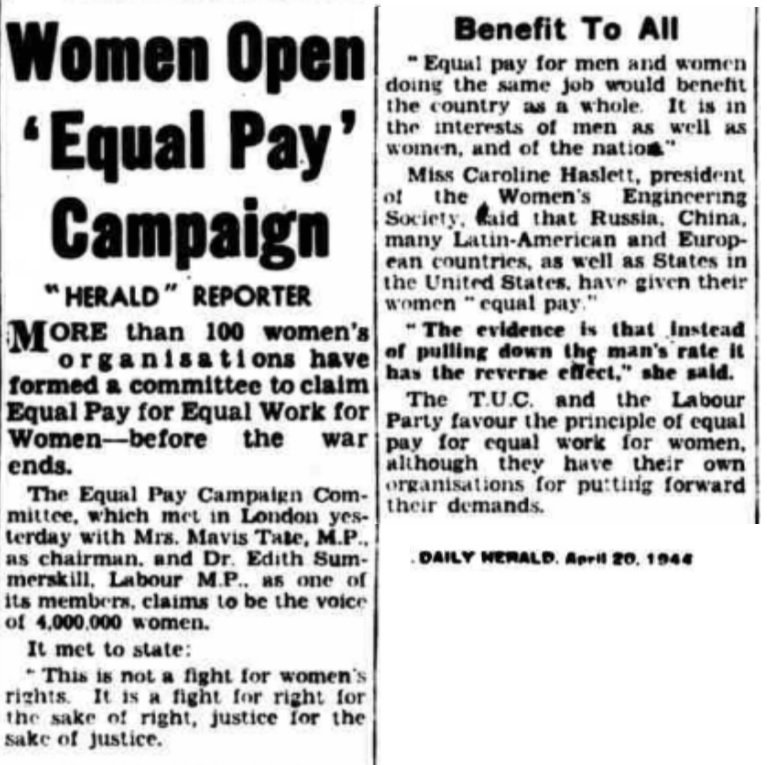

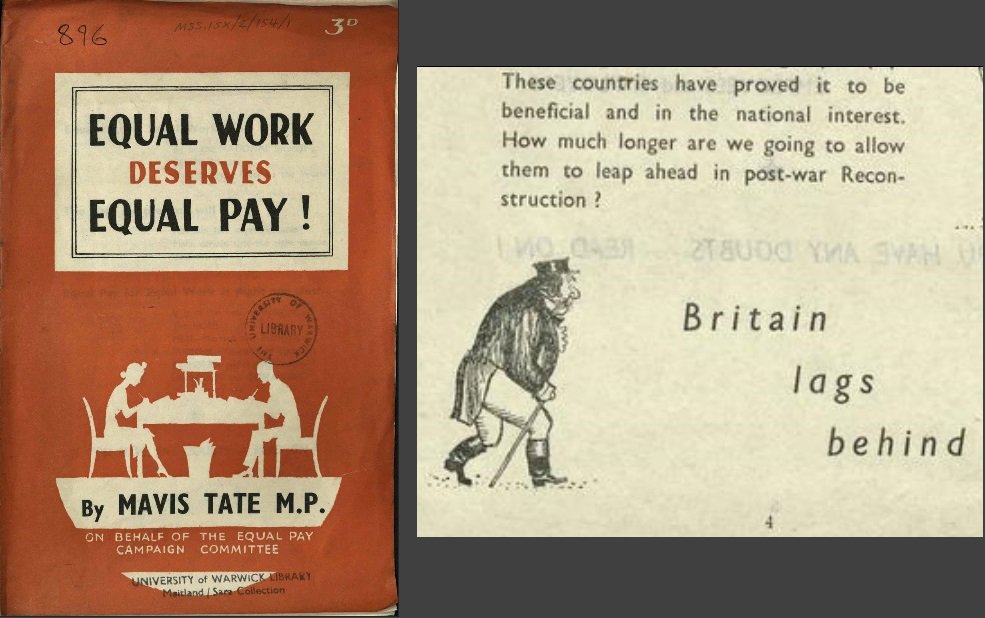

17. During the Second World War, the National Service act resulted in equal pay advocates calling for equal pay and equal compensation, with the Equal Compensation Campaign Committee (ECCC) proving very successful.

18. It was this success that led Mavis Tate to develop the ECCC into the Equal Pay Campaign Committee (EPCC), the campaign group that would lead the charge for equal pay in the civil service for the next 12 years.

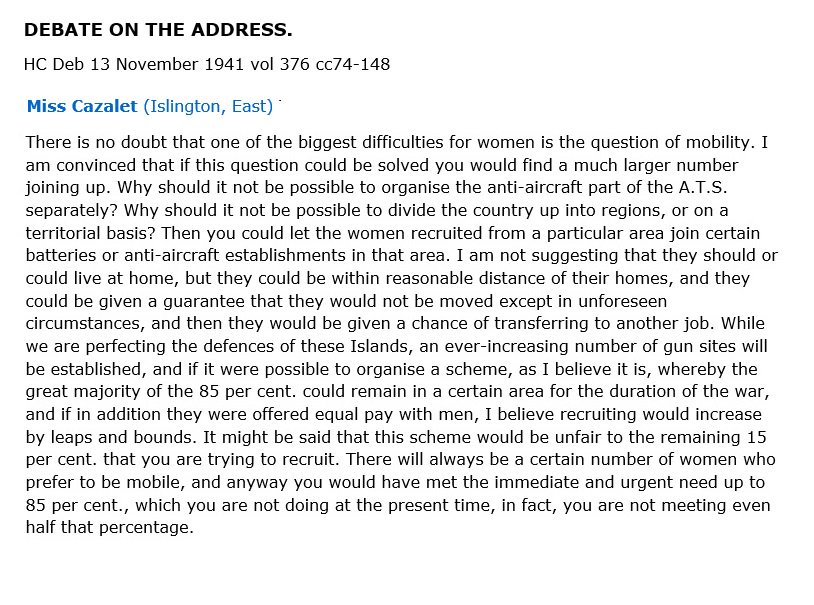

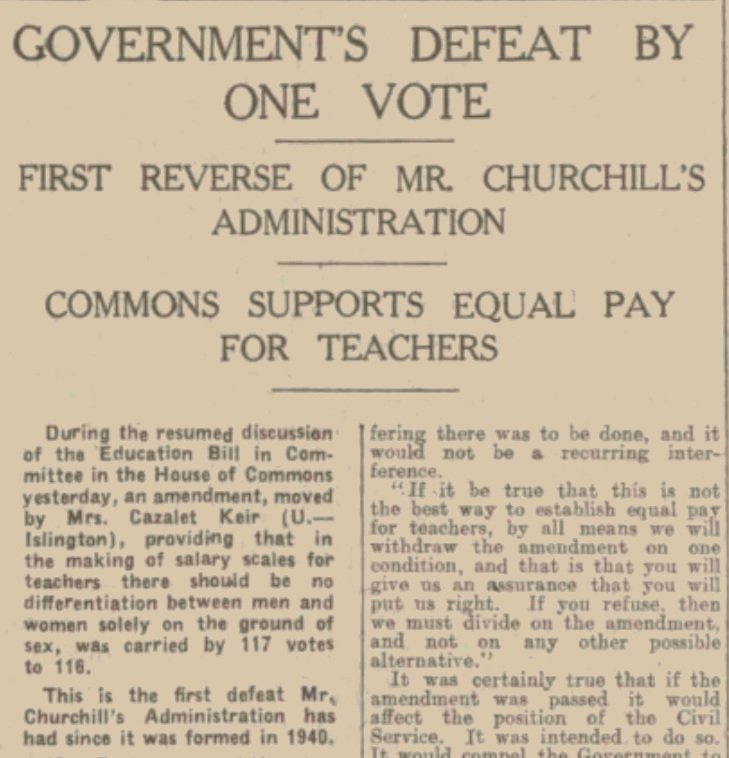

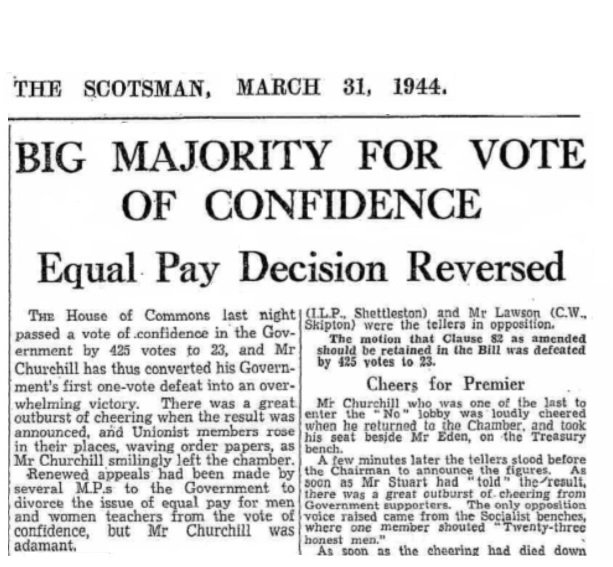

19. However, it was the Tory Reform Committee who were behind Thelma Cazelet-Kier bringing forward the next amendment to introduce equal pay for teachers.

It was Churchill’s only war cabinet loss. One he overturned on a motion of no confidence.

#EqualPayGroundhogDay

It was Churchill’s only war cabinet loss. One he overturned on a motion of no confidence.

#EqualPayGroundhogDay

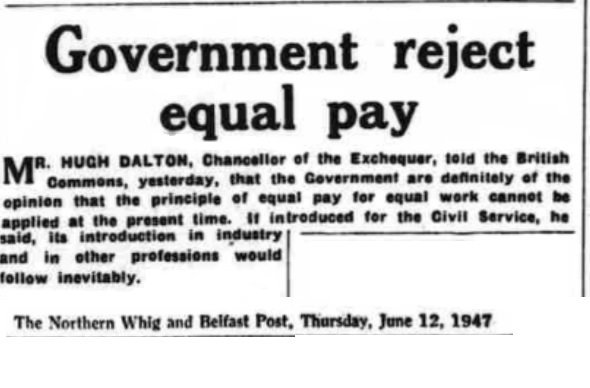

20. The year 1945 would see Clement Attlee take power, but Winston Churchill’s departure did not bring equal pay to the civil service because: ‘Now is not the time’.

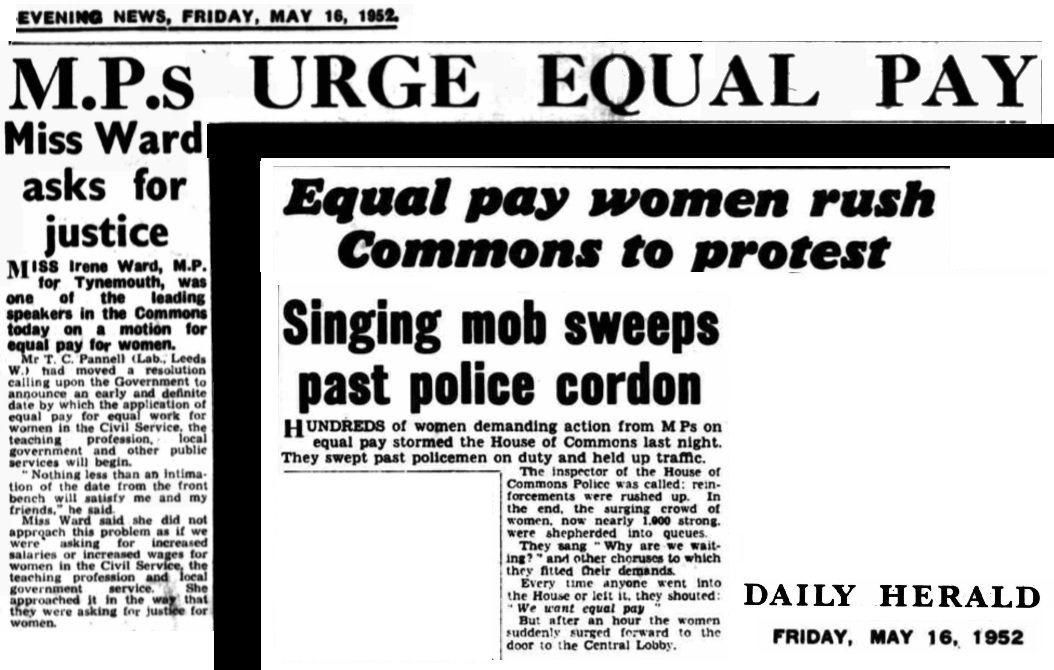

21. In 1950, a policy of equal pay for the civil service appears in both Conservative and Labour their 1950 manifestos, but goes absent in their respective 1951 manifestos, so the Equal Pay Campaign Committee arrange a motion to request a definite date.

22. In the run up to the 1955 election, to ensure the policy remained, the EPCC delivered a petition using a carriage driven by Emmeline Pankhurst’s driver. In a carriage behind rode an MP called Barbara Castle.

A year after the election, the EPCC declare success and dissolve.

A year after the election, the EPCC declare success and dissolve.

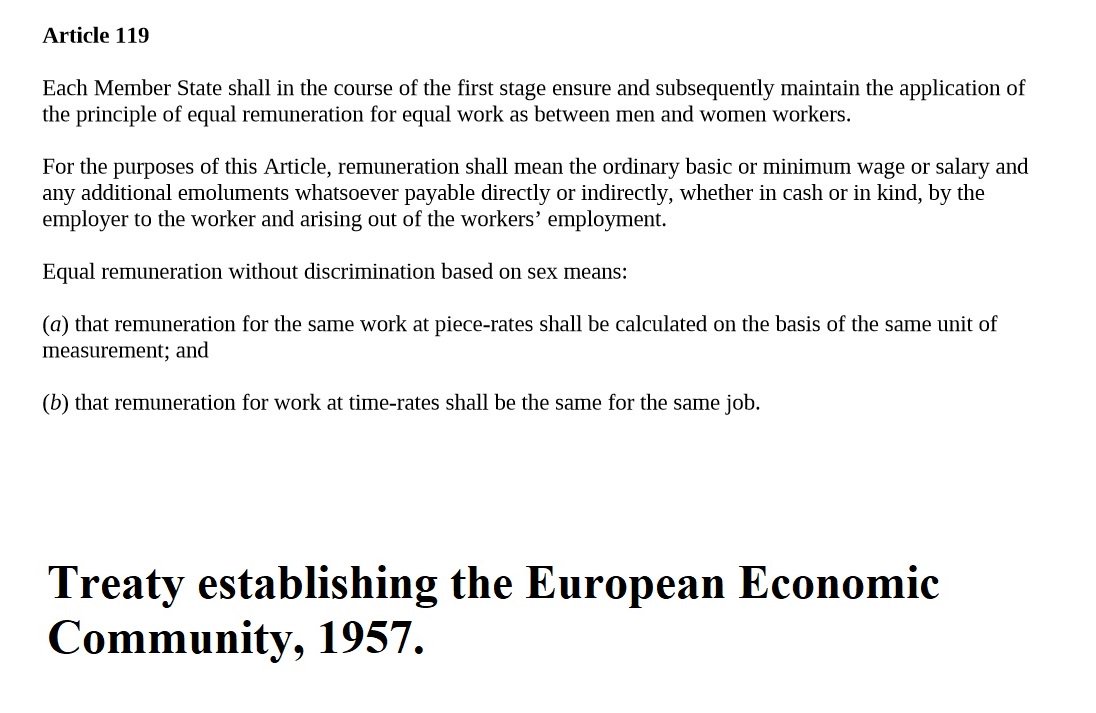

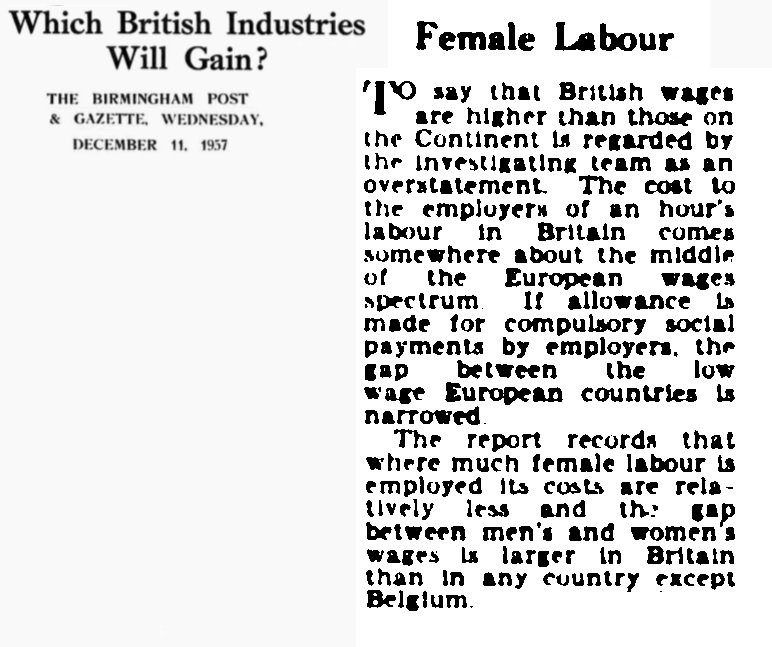

23. It would be just one year later, in 1957, when the European Economic Community began their 4 year programme to implement the first phase of the Treaty of Rome, including implementing equal pay.

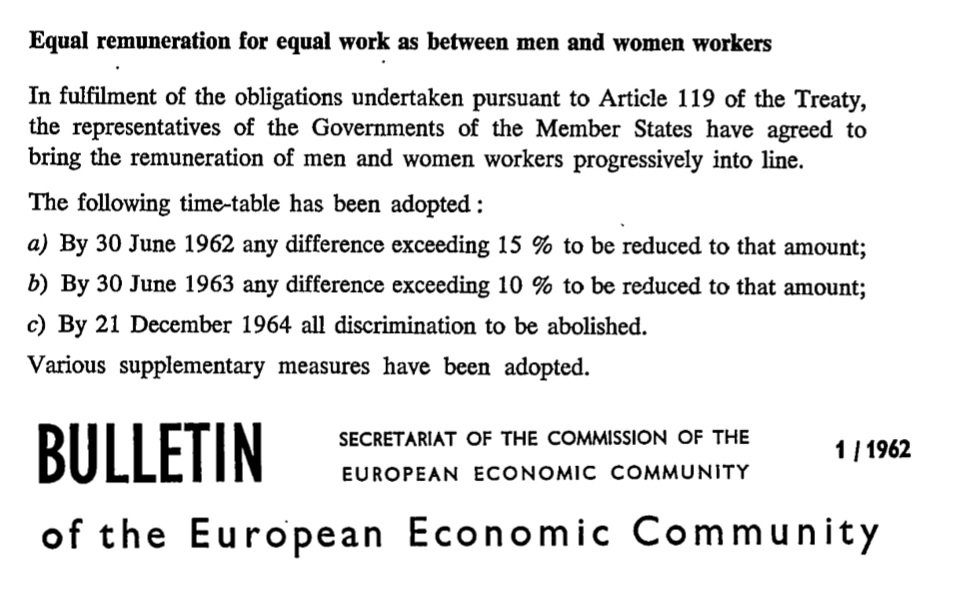

24. The memberstates began to discover that this was not as easy as they thought, but in 1961 it didn’t stop them agreeing to another ill-fated timetable that would attempt to eradicate inequality by 1964.

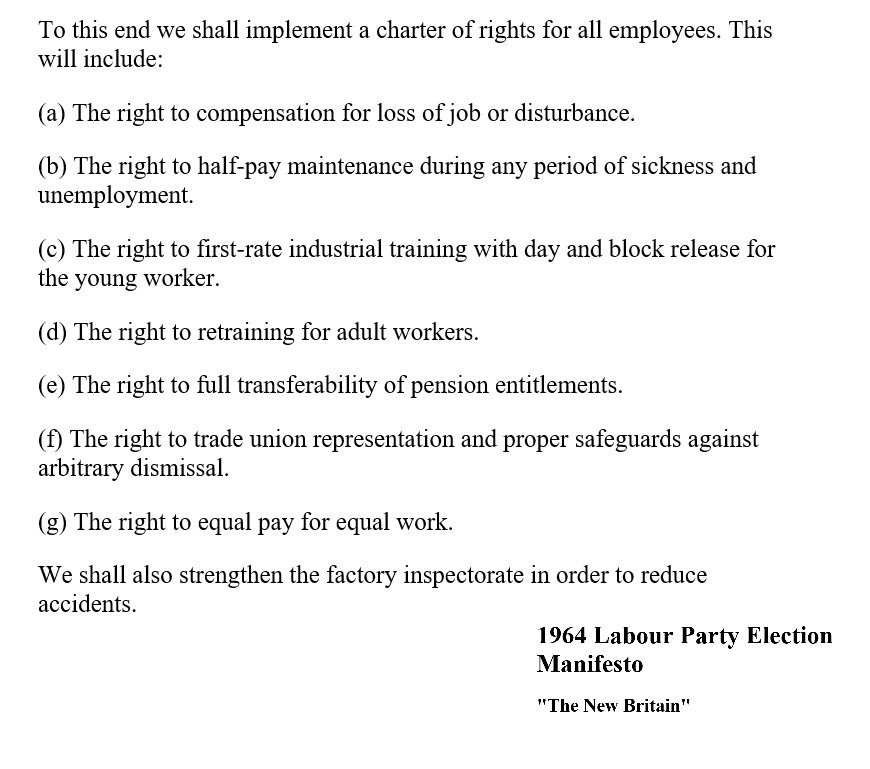

25. In 1964, when the EEC were failing on their timetable, the UK were voting in a government that had a manifesto commitment to introduce a charter of workers right, with one of them being equal pay.

26. By this time, the EEC was already setting the equal pay standard. It was cited in the United States Equal Pay Act debates, Article 119 had been used to interpret Italian law in the Perego vs Marzotto trial, and its existence was now a compelling argument in the UK.

27. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that after the 1966 election, and another commitment to equal pay, the UK government’s consultation with the unions and industry used the definition of Article 119.

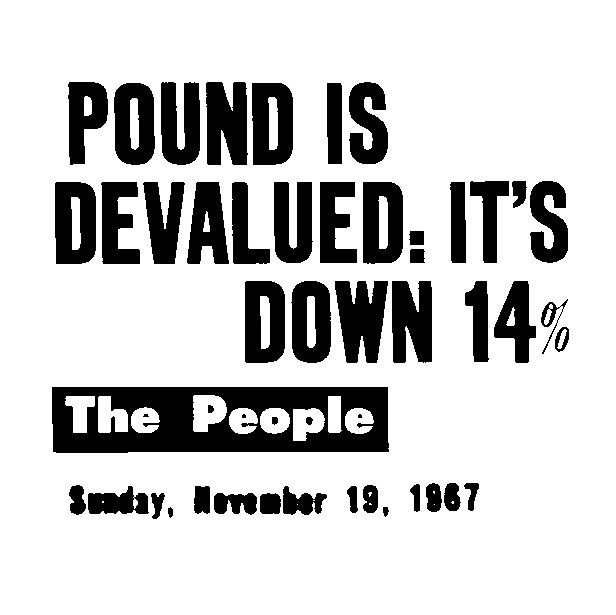

28. But the economy was going badly, and after the devaluing of Stirling in the autumn of 1967, it looked like the government were not going to deliver equal pay unless we joined the Common market.

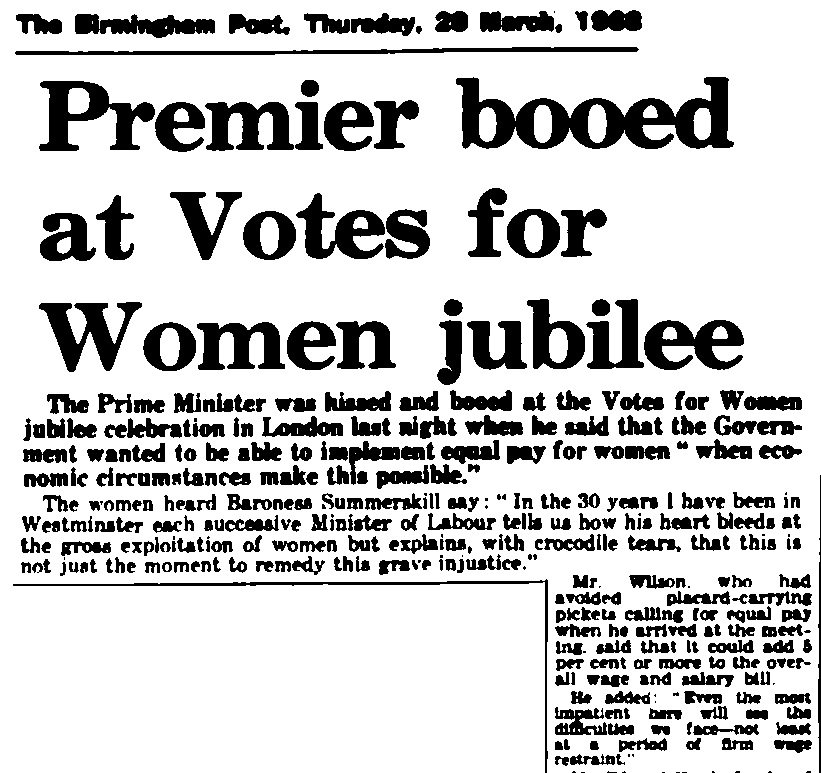

29. The events of 1968 were about to change that, or rather, the events of 1928 were about to change that.

The government’s decision to mark the jubilee of the Equal Franchise act ended up putting the policy centre state.

The government’s decision to mark the jubilee of the Equal Franchise act ended up putting the policy centre state.

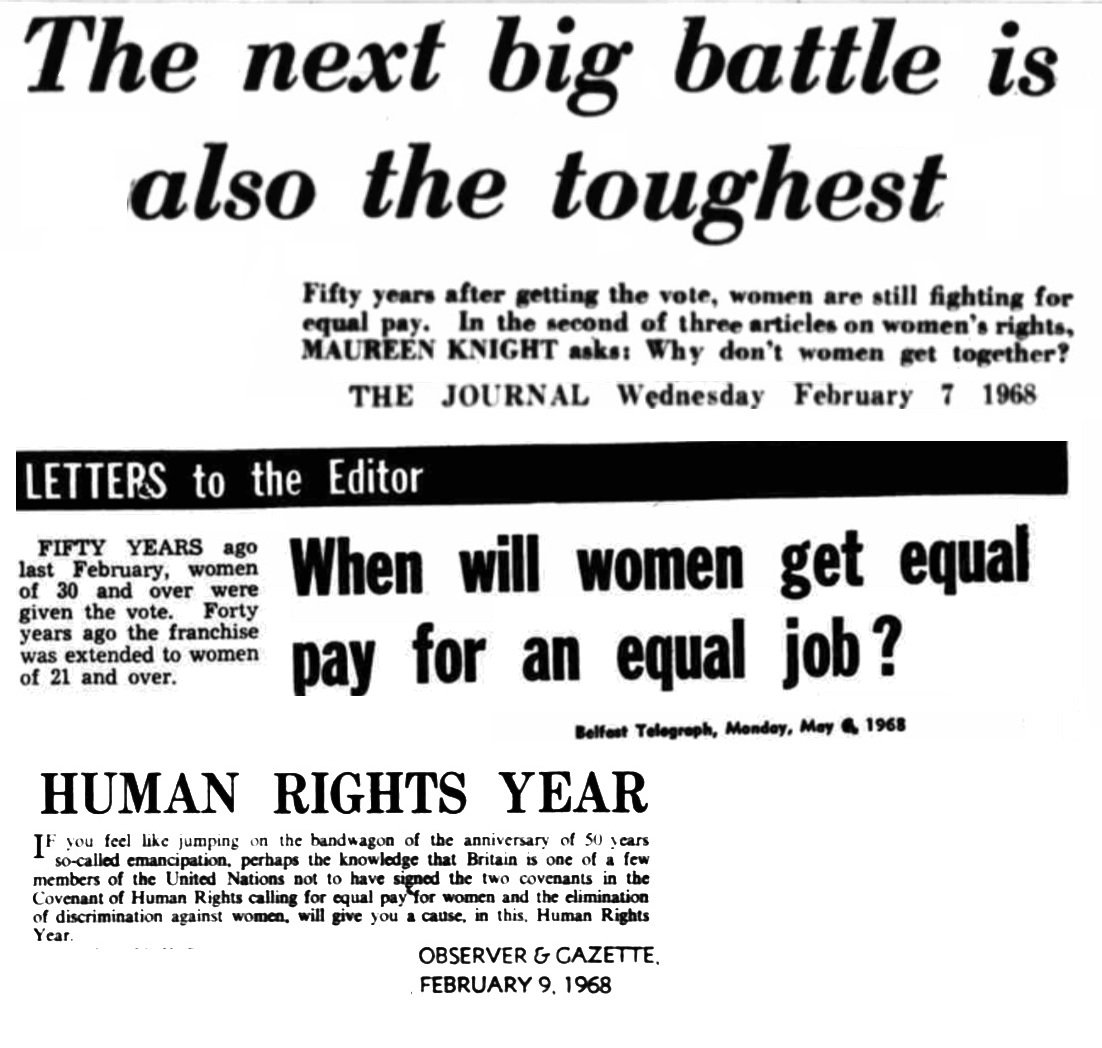

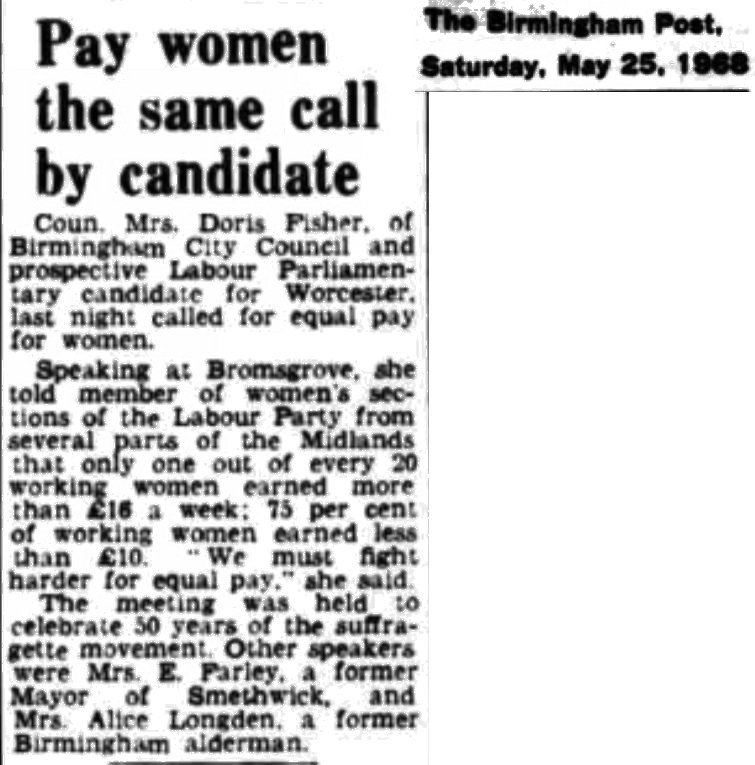

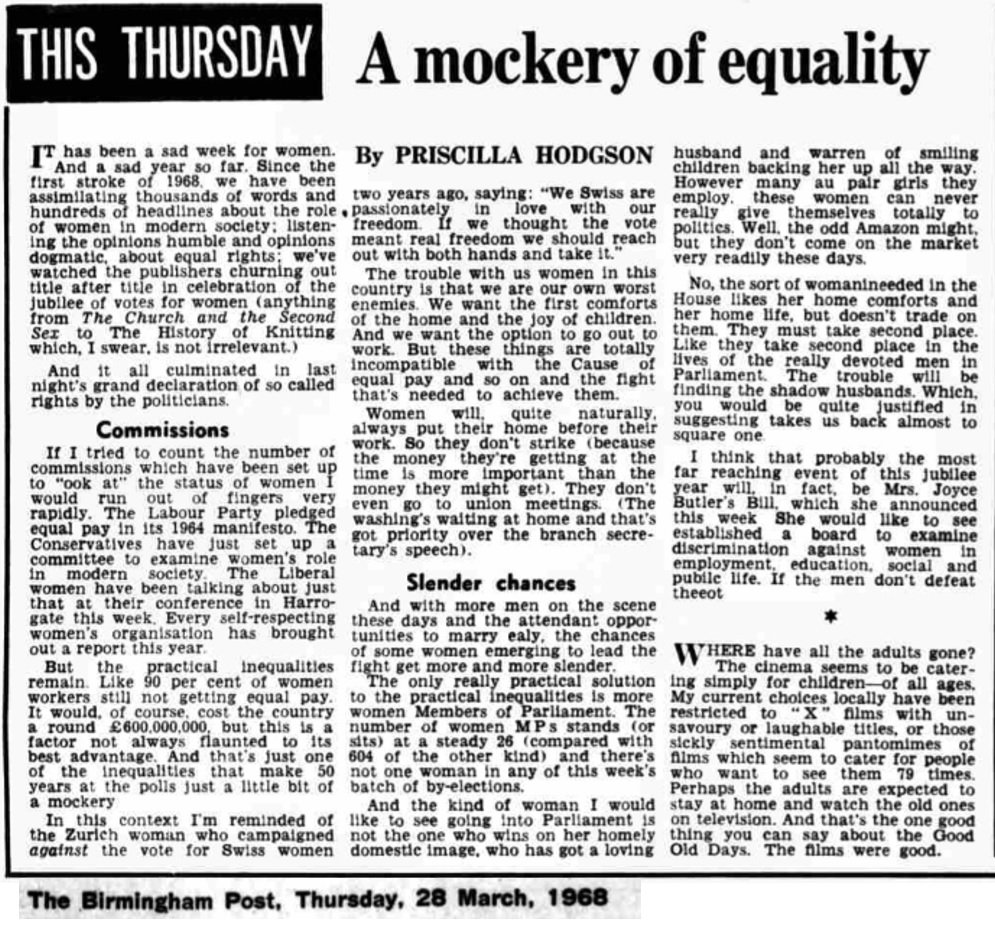

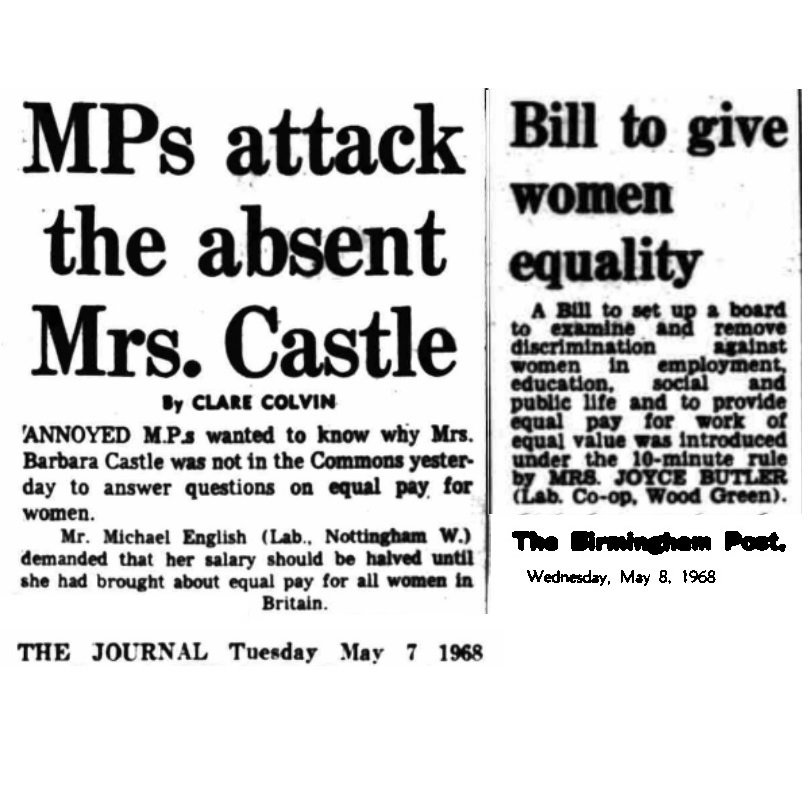

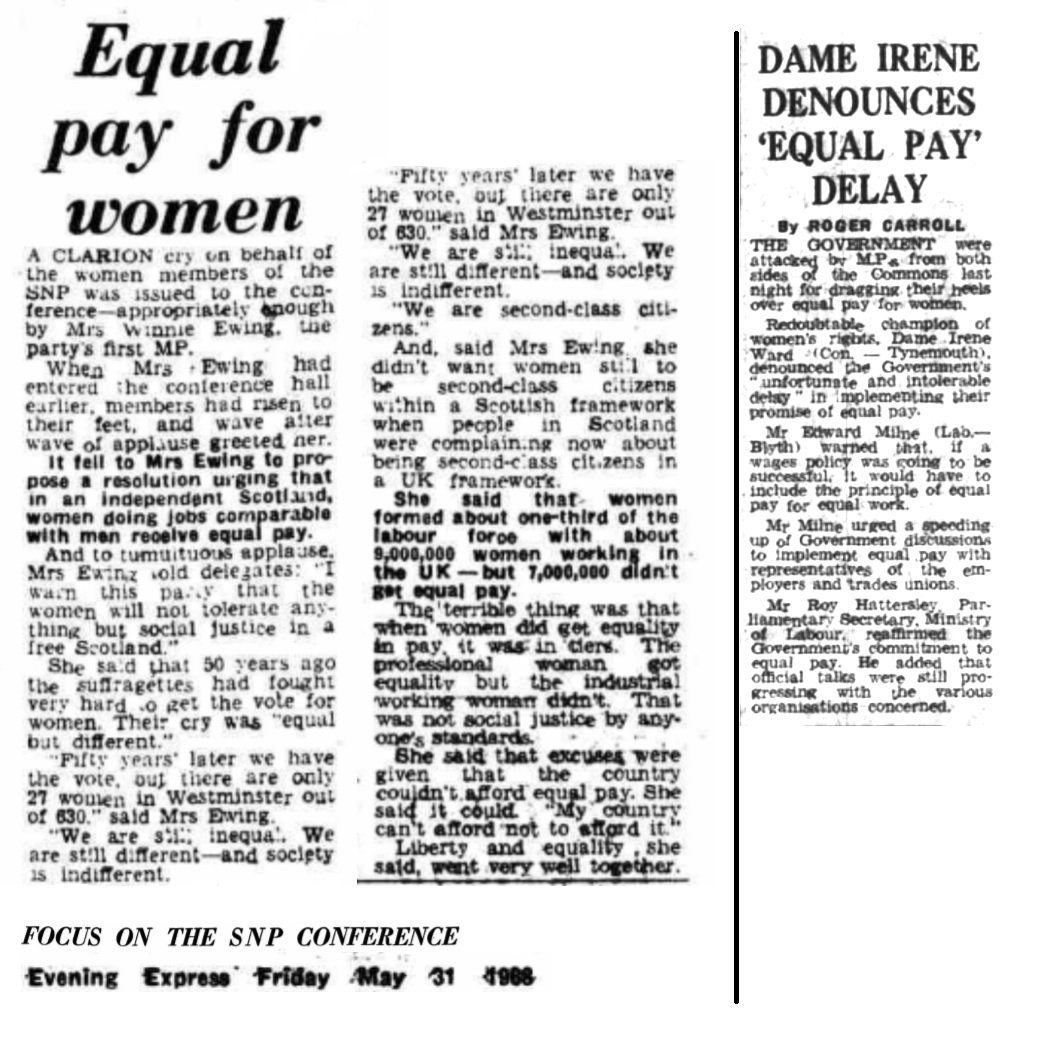

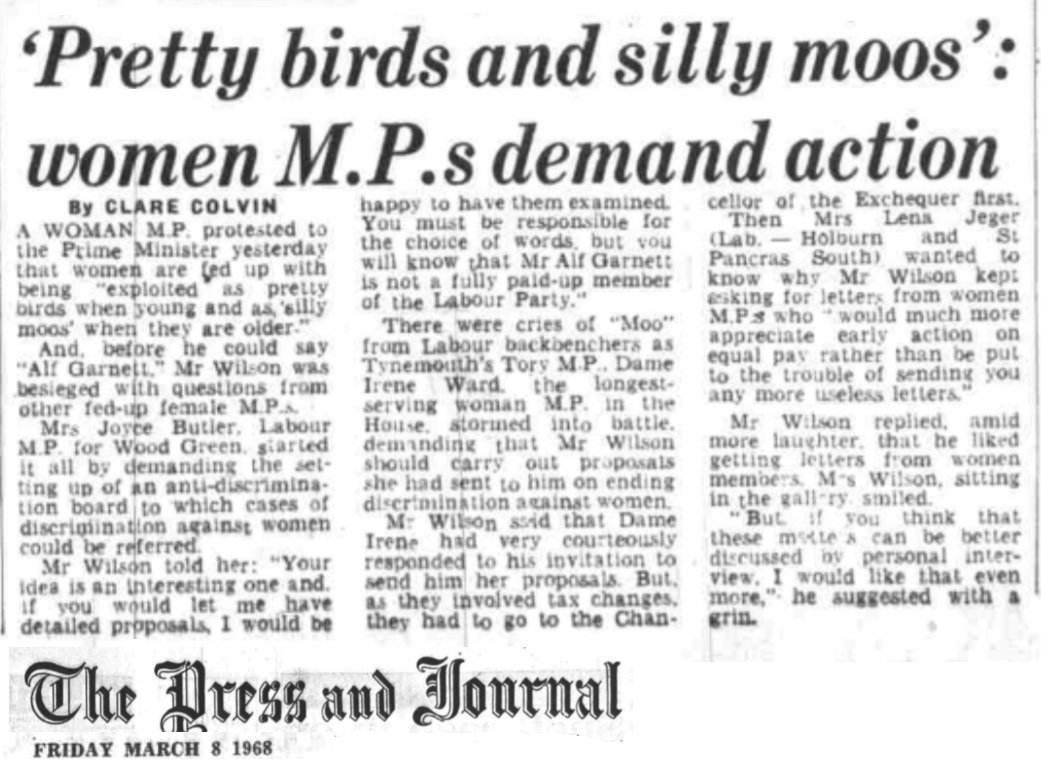

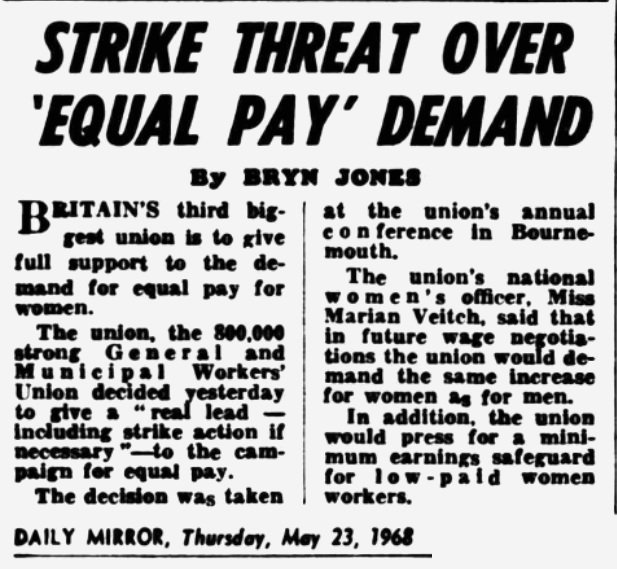

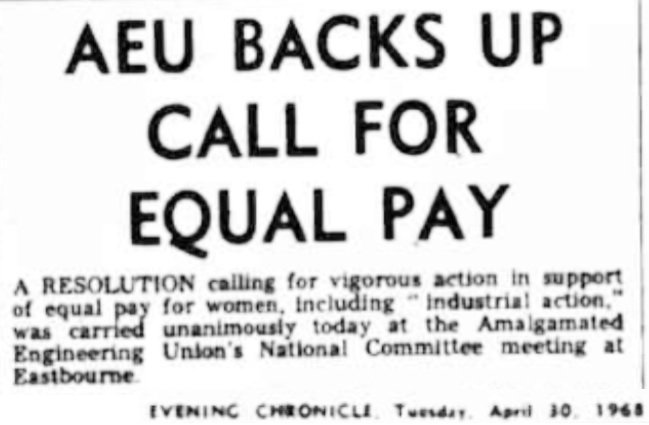

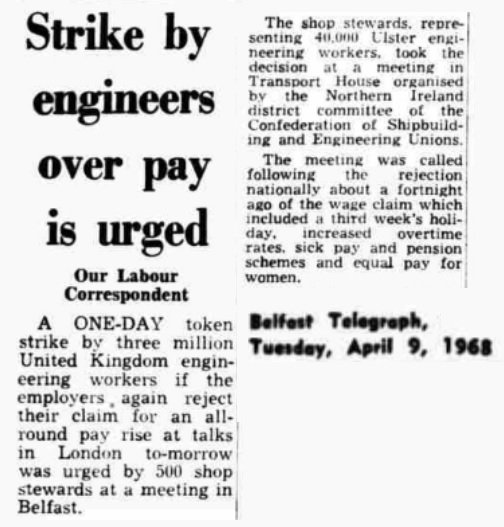

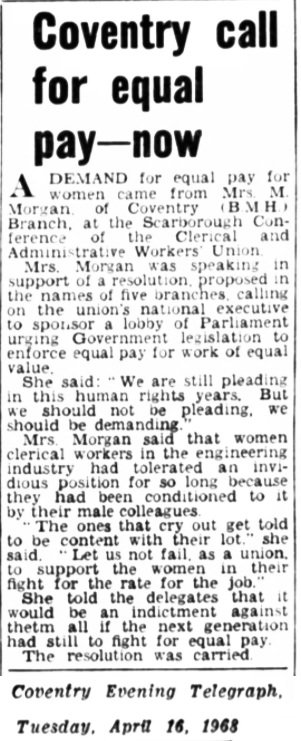

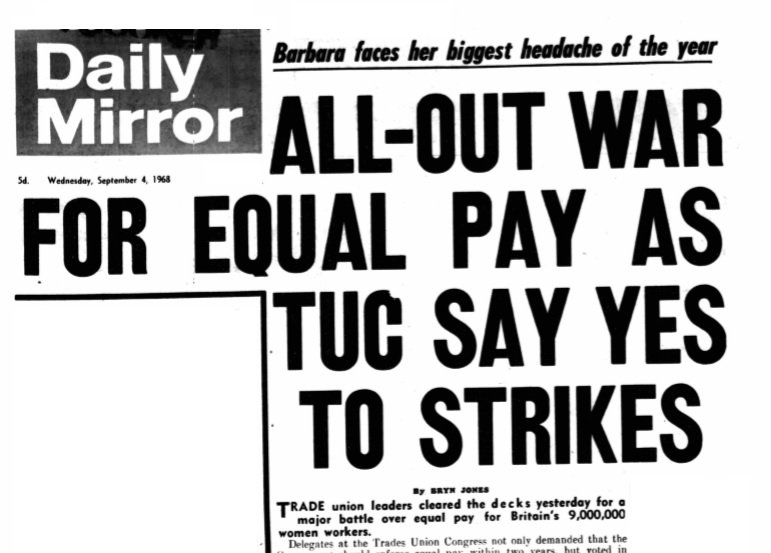

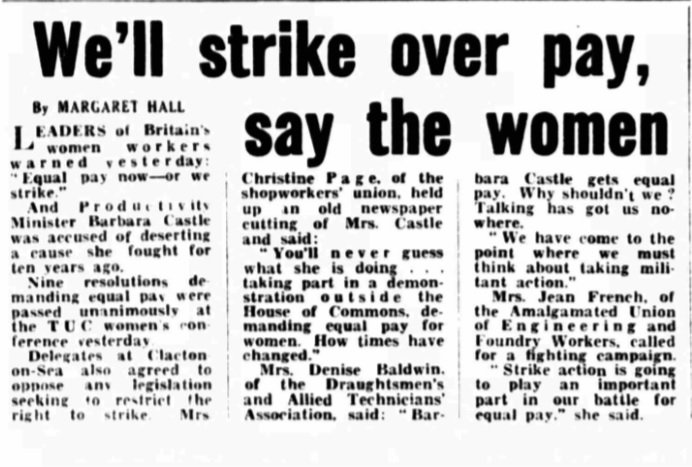

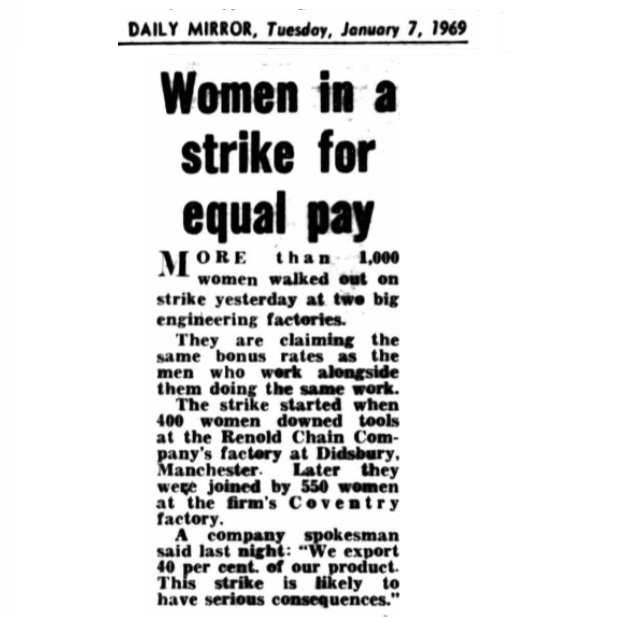

30. With probably more column inches referring to equal pay than at any other time, the public profile went up, and with that, the political heat went up. The government were facing pressure from every side.

31. And every angle, because the increased public profile reflected in the actions of the unions. Barbara Castle called for a meeting to resolve a dispute, that included equal pay in the demands, just 20 days after becoming Secretary of State for Employment.

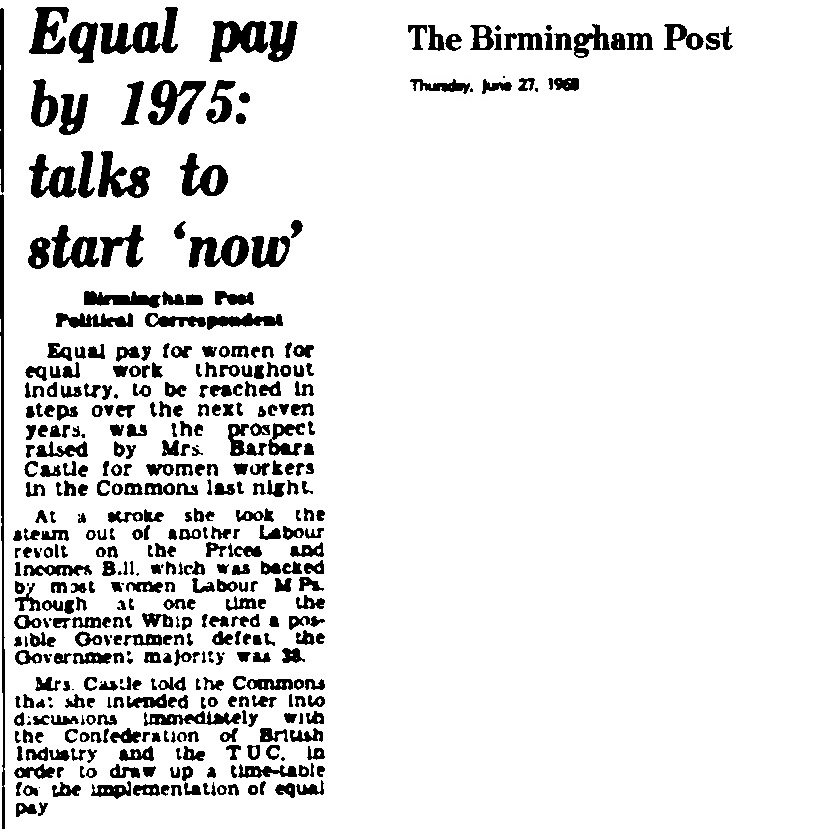

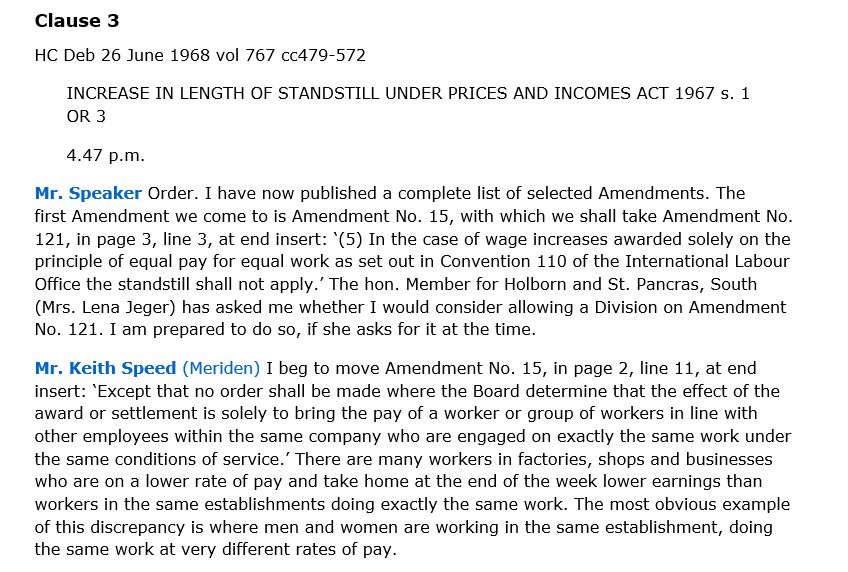

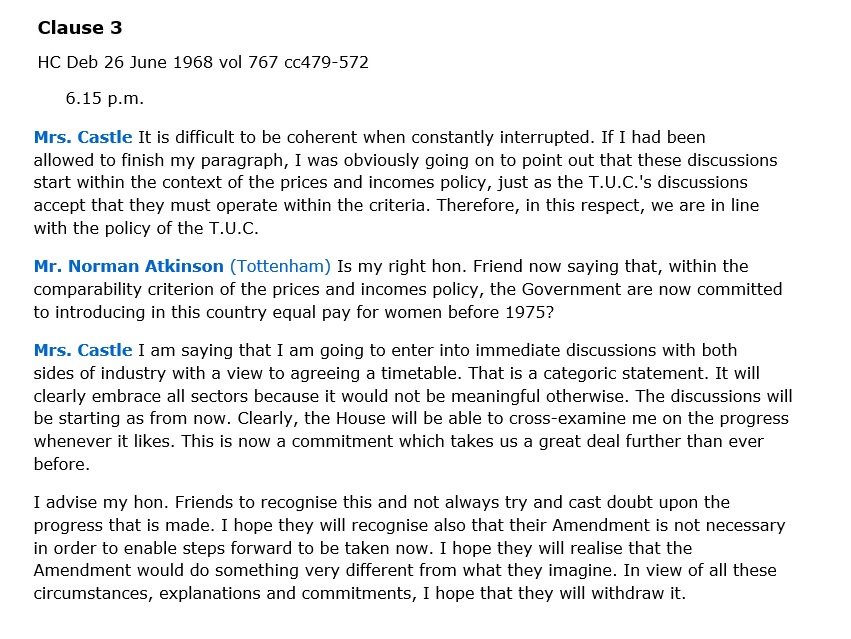

32. At the end of June, an equal pay amendment was put forward for the Prices and Incomes act which prompts Barbara Castle to persuade the leadership team that they would lose that vote if she can’t make an Equal pay announcement.

They agree!

They agree!

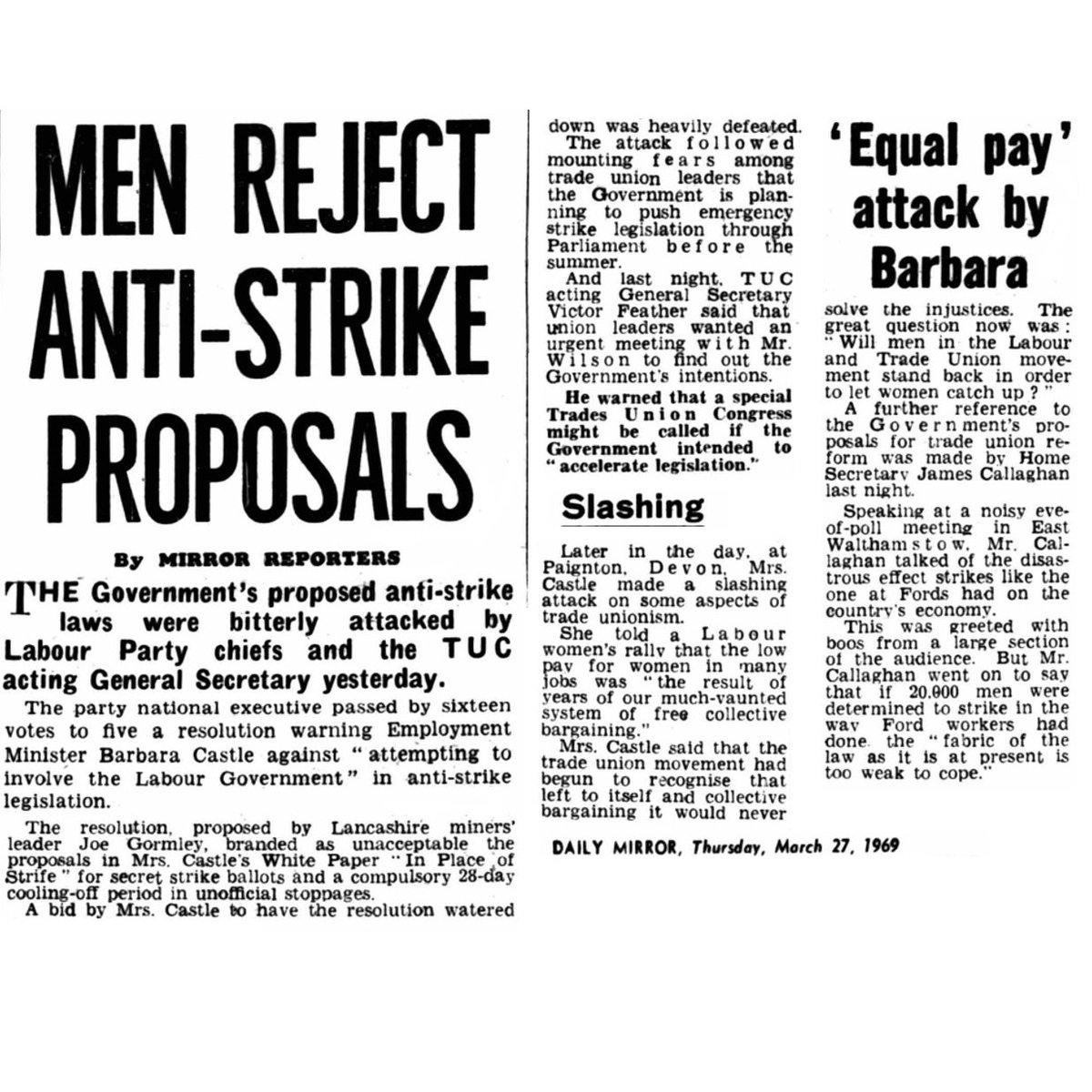

33. While it is true the strike at Ford led to the TUC equal pay motion, and strikes, at that time Barbara Castle was trying to prevent strikes and blaming the wage gap on the free collective bargaining of the unions.

She even went as far as complaining about the Ford strike.

She even went as far as complaining about the Ford strike.

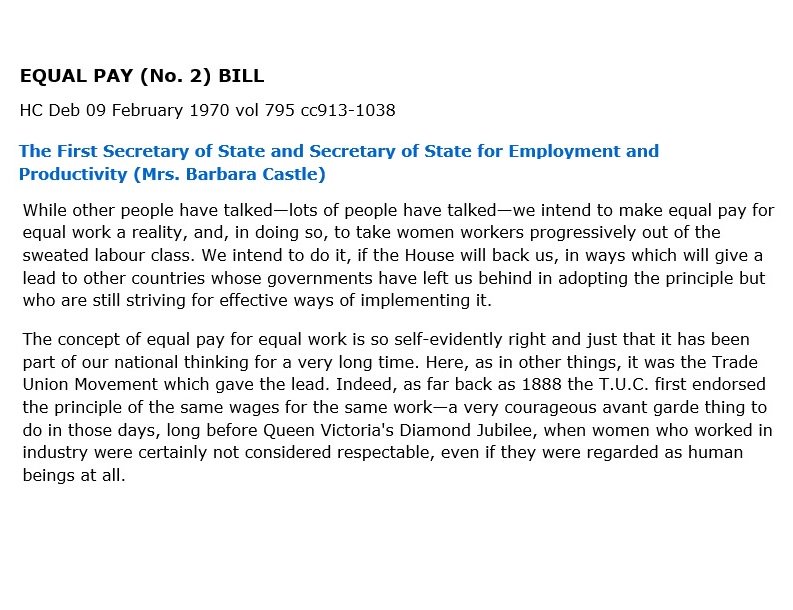

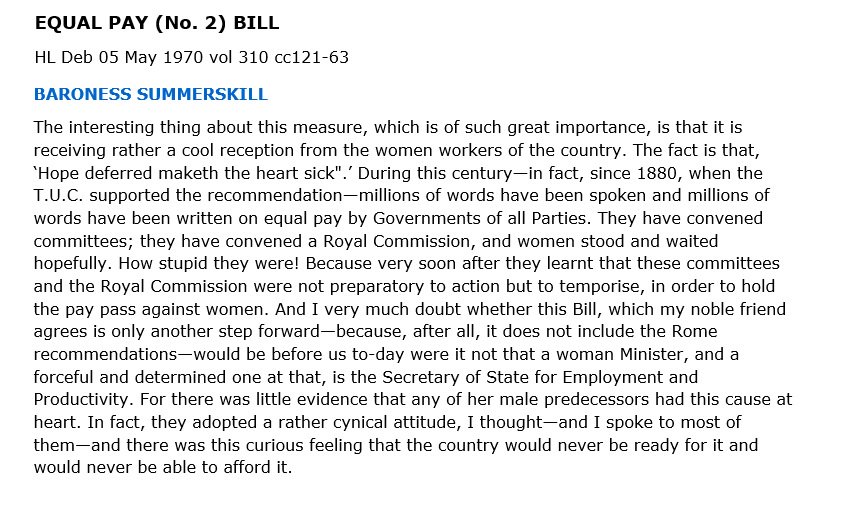

34. When parliament finally saw the Equal Pay act it was criticised for only covering equal pay for equal work rather than equal pay for work of equal value, but in fairness, this made the act quicker to deliver and simpler to interpret.

The UK was already playing catch-up.

The UK was already playing catch-up.

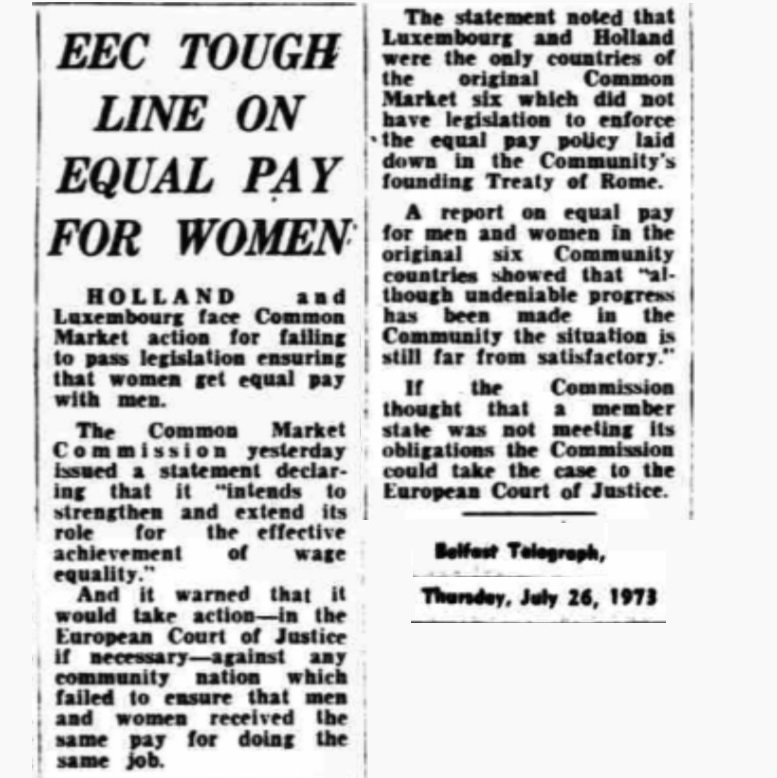

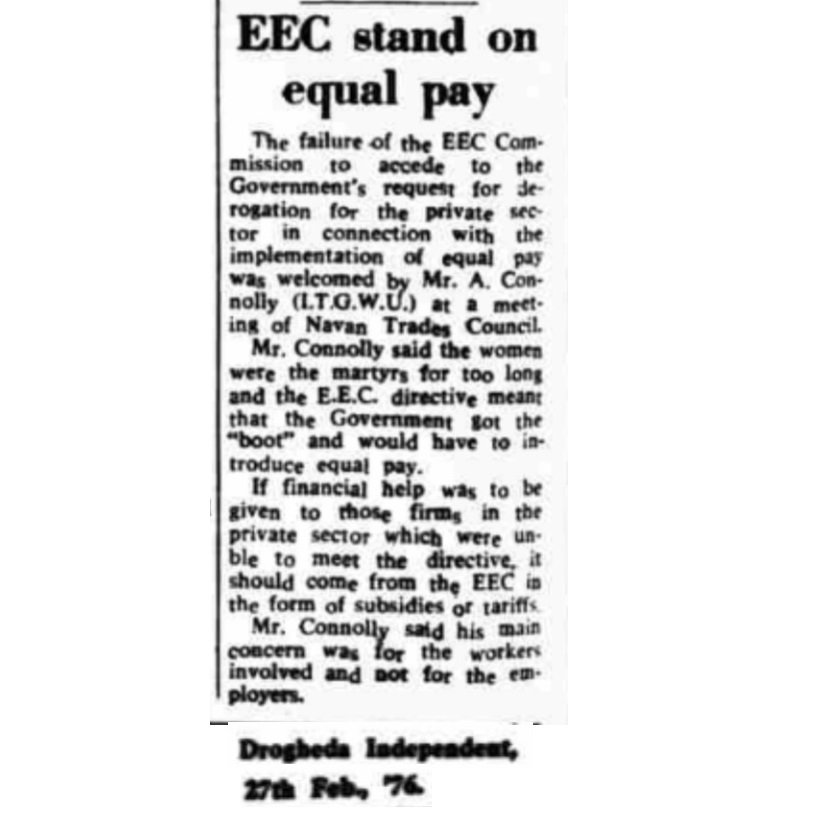

35. But the Act didn’t come into force until the 28th December 1975, and the EEC issued a directive in that year which called for a more advanced implementation. The act was effectively obsolete before it took effect.

36. Worse still, in 1976 the ECJ ruled that Article 119 had direct effect and was in effect on 1st January 1973.

Technically, the right to equal pay had been conferred on UK citizens by the Treaty of Rome nearly 2 years before any UK legislation was in force.

Technically, the right to equal pay had been conferred on UK citizens by the Treaty of Rome nearly 2 years before any UK legislation was in force.

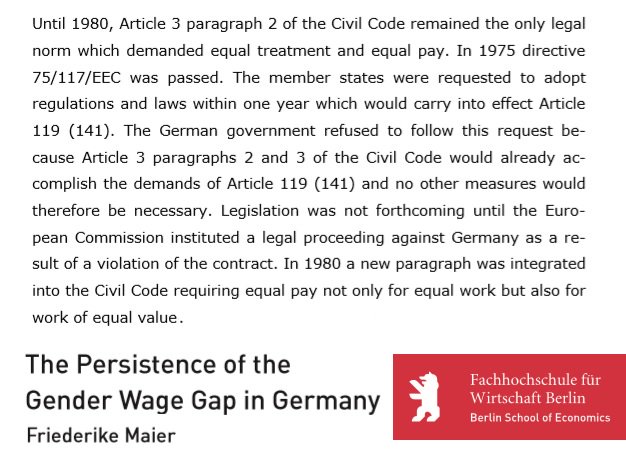

37. And it doesn’t end there because the EEC were always firm on Article 119, but at the end of the 1970s no countries had implemented their directive, and so they began to threaten court action.

When they did this to Germany, it complied.

When they did this to Germany, it complied.

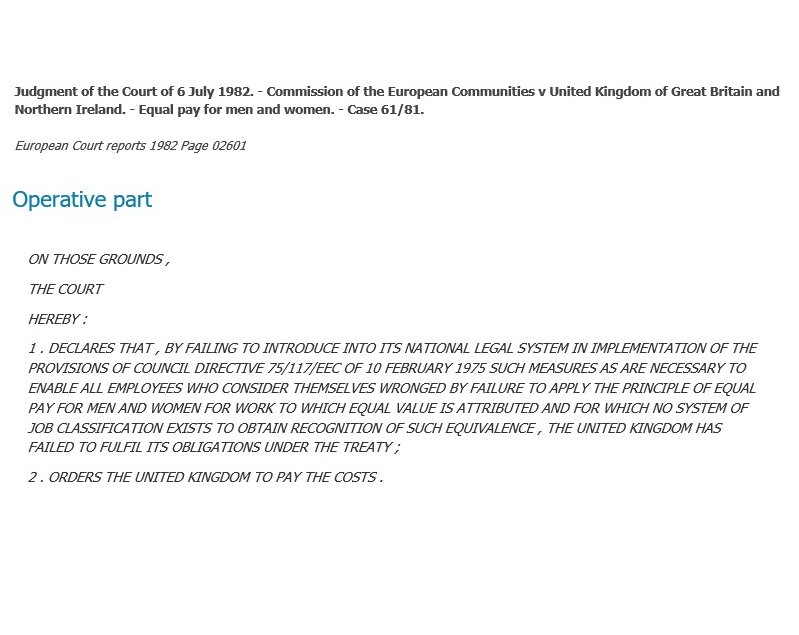

38. By 1982 it was the UK’s turn. Despite domestic pressure to implement the directive, and legal advice suggesting they would lose, the UK government decided to fight the commission and it inevitably lost.

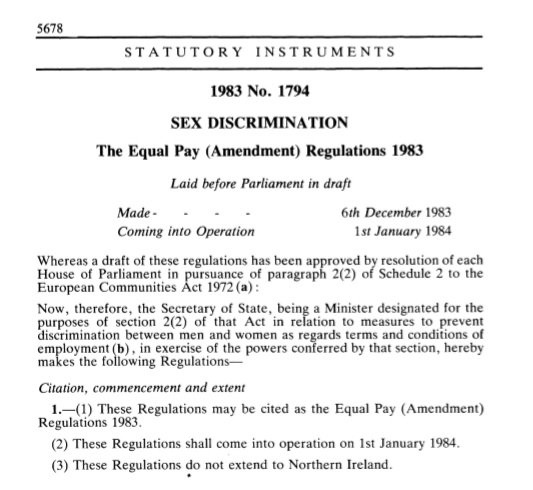

39. Which led to equal pay for work of equal value in just 2 years. No damaging strikes. No 10 year campaigns. No parliamentary flips.

40. Nothing said it better than the Equal Pay Campaign Committee pamphlet: “Britain lags behind”. With regard to equal pay in the civil service, Britain had been nearly 30 years behind.

Thanks to the ECJ, the UK had finally caught up with Europe.

Thanks to the ECJ, the UK had finally caught up with Europe.

41. It was a long haul, and there was no fairy-tale where a single strike led to the fairy godmother introducing legislation 2 years later. Barbara Castle referred to it as ‘trade union hagiology’.

42. Hundreds, maybe thousands of organisations were involved and it started when women were united by the vote and the war.

43. In the year 1968, people were reminded that the Suffragist movement was about more than just the vote. It was just the beginning.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter