I need an excuse to procrastinate, so I’m starting a series of threads on the letter ض. You may remember @phdnix ‘s fantastic thread from several months back demonstrating how the pronunciation of the classical ض was distinct from the modern pronunciation https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1086975053793841152">https://twitter.com/PhDniX/st...

My threads will elaborate from Tajwīd tradition (forgive me linguists),& I will show that a proper comprehension of classical tajwīd texts should lead to the same conclusion that the preponderant pronunciation of ض today is not the same one described by classical Tajwīd scholars.

Warning for the sensitive: the conclusion of these threads is that your favorite reciter or Quran teacher may not be pronouncing ض “correctly” ("correctly" hereby means how it was pronounced by the earliest Tajweed scholars and presumably the Prophet ﷺ)

But later on I will also show that fortunately, the original pronunciation of ض has been preserved in surviving asaneed (chains of transmission)! The tradition has not broken, but has merely become unpopular over time.

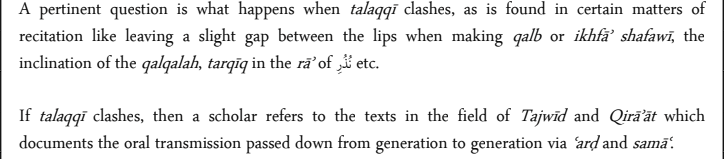

Before diving in, it& #39;s important to first understand the guiding principles the founding-fathers of Tajwīd laid down to deal with conflicting pronunciations among asaneed. Saleem Gaibie succinctly lays it out at the end of his short treatise linked here https://www.al-tanzil.co.za/legacy-of-tajwid/">https://www.al-tanzil.co.za/legacy-of...

He explains that whenever there is an inconsistency between talaqqi (oral transmission) and texts, texts should always be given precedence. And whenever two chains of transmission clash, the correct one is whichever is backed up by the texts!

He quotes Makki ibn Abi Talib and Abu Amr ad-Dani who both assert that one who relies solely on oral transmission alone without assistance from and proper comprehension of the texts is "feeble and weak" who will undoubtedly err in recitation and teaching

Qari Saleem adds that it& #39;s extremely sad to see teachers and students of this field display poor understanding of Tajweed theory, and they fall prey to the common misconception that talaqqi alone is considered sufficient mastery of the subject.

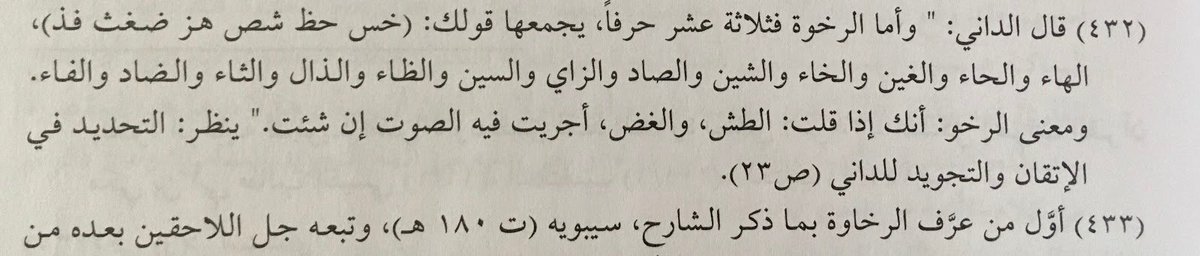

Now onto ض! Those familiar with Tajweed know that a letter consists of: 1. its articulation point (makhraj) and 2. its traits (sifaat), both of which @PhDniX briefly covers in his thread. I& #39;m going to concentrate on the trait of rakhāwah (frication) and its significance

The proto-ض has unanimously been described as rikhwah (letter belonging to the rakhāwah category) which means, in layman& #39;s terms, that air is able to flow out of the mouth throughout the duration of pronouncing this letter.

The letters of rakhāwah are [ث ح خ ذ ز س ش ص ظ غ ف ه]. Notice how their sounds are able to continuously flow insofar as there is air in your lungs! The consensus of classical scholars has always been that ض is a letter of this category.

The opposite of rakhāwah the trait of shiddah (plosive or stop), which is when air is prevented from flowing out of the mouth when pronouncing the letter. Those letters are [أ ج د ق ط ب ك ت ]. The neo-ض (the popular one present-day) very clearly fits this category.

The main argument of contemporary proponents and defenders of the neo-ض [such as the one below] is that rakhāwah is supposed to act differently for ض. This claim is unsupported by classical Tajweed texts. Let& #39;s take a look at how classical scholars defined rakhāwah!

Abu Amr ad-Dani defines rakhāwah simply by providing examples. He shows that if you pause on (sukoon) or double (tashdeed) a letter of rakhāwah like ش, "you can allow the sound of the letter to flow as you wish." He makes no exception for ض, using it in fact as a 2nd example!

Ibn al-Jazari also provides the same definition that the sound of the letter flows from the mouth and after providing a couple examples, says, "and the same applies to the rest of the rakhāwah letters," making no exception for ض

Classical lexicons such as Lisan ul Arab provide a nearly identical definition. I remember seeing one that actually spelled out the examples like لمسسس and الرششش (unfortunately I can no longer find it).

It& #39;s clear that the popular neo-ض does not possess the trait described above, because it& #39;s quite impossible to pronounce it with indefinite airflow. The sound of the neo-ض becomes obstructed and is unable to flow out of the mouth.

What& #39;s interesting is that proponents of the neo-ض cannot re-categorize ض as a shiddah letter as that would be going against centuries of consensus, so they’re forced to reinterpret what rakhāwah means in relation to ض [as shown 5 tweets prior].

The problem this causes is it implies that over 10 centuries of scholarship were too incompetent to point out that the rakhāwah for ض is unique, which would be a very important detail! Highly unlikely as scholars of Tajweed were known for their meticulous detail in descriptions!

One common argument of neo-ض proponents is that the trait of istiṭālah, a trait unique to ض, allows their plosive ض to be considered a letter of rakhāwah. So let& #39;s digress briefly to discuss what istiṭālah is, and whether or not the opposition has a case.

Ibn al-Jazari provides the standard definition: istiṭālah is the phenomenon that occurs when the ض "lengthens" from its articulation point and reaches towards that of ل.

So what is this "lengthening?" Most scholars like Makki seem to incline towards the view that it is the sound of the ض which travels along the side of the tongue from the wisdom tooth to the first pre-molar (right behind the canine). This "traveling" of sound is what is intended.

Qari Muhammad Shareef explains in Sabīl-ur-Rashād fī Tahqīqi Talaffuẓ aḍ-Ḍād, "Because of istiṭālah, a lengthiness/extension of sound is found in ض that is not found in other letters...because the ض has the longest makhraj, thus it has the most extended sound."

I won& #39;t linger on istiṭālah for much longer, but the point is that there is nothing in classical literature at all which suggests any causal link between rakhāwah and istiṭālah, as contemporary Qurra& #39; argue.

Nothing in the definition or application of istiṭālah prevents air flow, nor is there anything in it that could fulfill the definition of rakhāwah while the sound of the letter remains trapped in the mouth. Both are independent traits.

Another point I& #39;d like to add is that if the rakhāwah for ض were truly distinct from the rest of the rakhāwah letters as neo-ض proponents claim, or even if the rakhāwah found in it were less intense, there is a whole category in between rakhāwah and shiddah for such letters!

This category, known as bayniyyah or tawassut, consists of [ ل ن ع م ر ] (and some linguists include و & ي ) which the classical scholars describe as points between the rakhāwah and shiddah spectrum.

Not a single classical scholar has ever classified ض as anything other than fully rikhwah, though there were not arbitrarily bound to do so. They could have differed, but there was no sense of ambiguity that the sound of ض flows.

With that in mind, it should be plain why it would be absurd to entertain the idea that the neo-ض allows more airflow than a letter like ل (or any other letter of bayniyyah)but that is what is implied if one tries to argue that the present-day ض is what is intended by the texts!

So what IS the ض supposed to sound like? What is it not supposed to sound like? What does it sound similar to? What is it easy to confuse with in regard to sound? What is it easy to confuse with in regard to application? The classical texts cover all of these issues.

Let& #39;s first discuss what the present-day ض sounds like, which is undeniably like an emphatic د (i.e. a د with tafkhim or itbaq). This leads many folks who have trouble with emphatic sounds to pronounce the ض as…

a د, or to confuse it as an emphatic د, just as they have trouble with ط، ظ ، ص (pronouncing them as ت، ذ ، س respectively). Contemporary Tajweed scholars often highlight words like عضدا، منضود، مخضود as words in which extreme care is required to distinguish clearly btwn ض and د

Mixing up ض and د is a fairly recent phenomenon and doesn& #39;t seem to be a concern for classical scholars. They seem to be much more concerned with, no actually, downright obsessed with making sure ض isn& #39;t confused for ظ! A lot more on that later.

Another common "mistake" that occurs with the present-day ض is in words like الأرض, يقبضن، نضرة (pausal form), etc. with qalqalah, whereas ض is not a qalqalah letter. This is totally expected when we take into account that the neo-ض is a shiddah letter and no longer rakhāwah

Tajweed enthusiasts know that qalqalah is linked with shiddah. Because the nature of shiddah letters is that their sound is obstructed, qalqalah allows them the opportunity to be heard when stopping on them (ء ت ك are exceptions to this, but that& #39;s a different discussion).

So intuitively, the present-day ض SHOULD have qalqalah and it& #39;s very counter-intuitive to not pronounce it with qalqalah. Since Tajweed is usually quite intuitive, it seems odd to forcefully and awkwardly prevent a plosive letter from being fully realized.

Of course, the classical Tajweed scholars never faced this issue as the problem vanishes with the correct pronunciation of the fricative ض (letters of rakhāwah do not require qalqalah to be audible)

That& #39;s enough for traits. My next thread will discuss how a plethora of scholars from a multitude of fields (grammarians, qurrā’, historians, fuqahā’) all wrote (rather excessively) about the uncanny resemblance in sound between ض and ظ (and ذ and even ز)! Stay tuned!

Part 2: https://twitter.com/ZaadFather/status/1194816685103964160">https://twitter.com/ZaadFathe...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![The main argument of contemporary proponents and defenders of the neo-ض [such as the one below] is that rakhāwah is supposed to act differently for ض. This claim is unsupported by classical Tajweed texts. Let& #39;s take a look at how classical scholars defined rakhāwah! The main argument of contemporary proponents and defenders of the neo-ض [such as the one below] is that rakhāwah is supposed to act differently for ض. This claim is unsupported by classical Tajweed texts. Let& #39;s take a look at how classical scholars defined rakhāwah!](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EJOyYefU8AU6x7m.png)