THREAD. Artificial watercourses across the Cambridgeshire #fenland are called ‘lodes’ locally - from the Old English (ge)lād (derived from the verb ‘to lead’) - because they lead water from one place to another. Why was that necessary? The #landscape holds the clues..

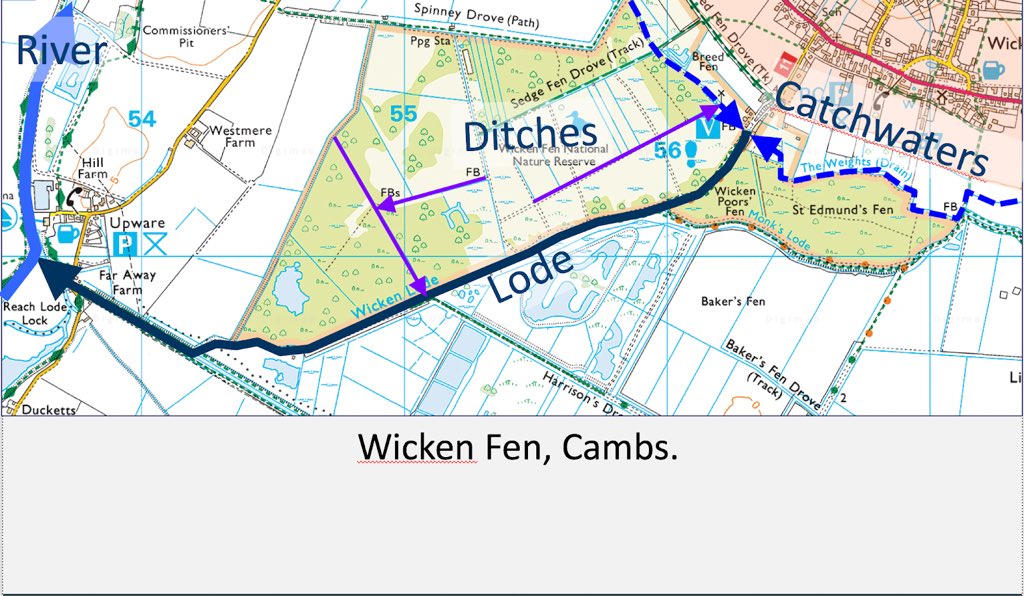

2. Lodes are the largest in an interconnected hierarchy of man-made watercourses - the other two in that list are catchwaters and ditches. We’ll start with lodes, move on to catchwaters, and then to ditches - and suddenly the whole landscape makes sense (at least, to me)

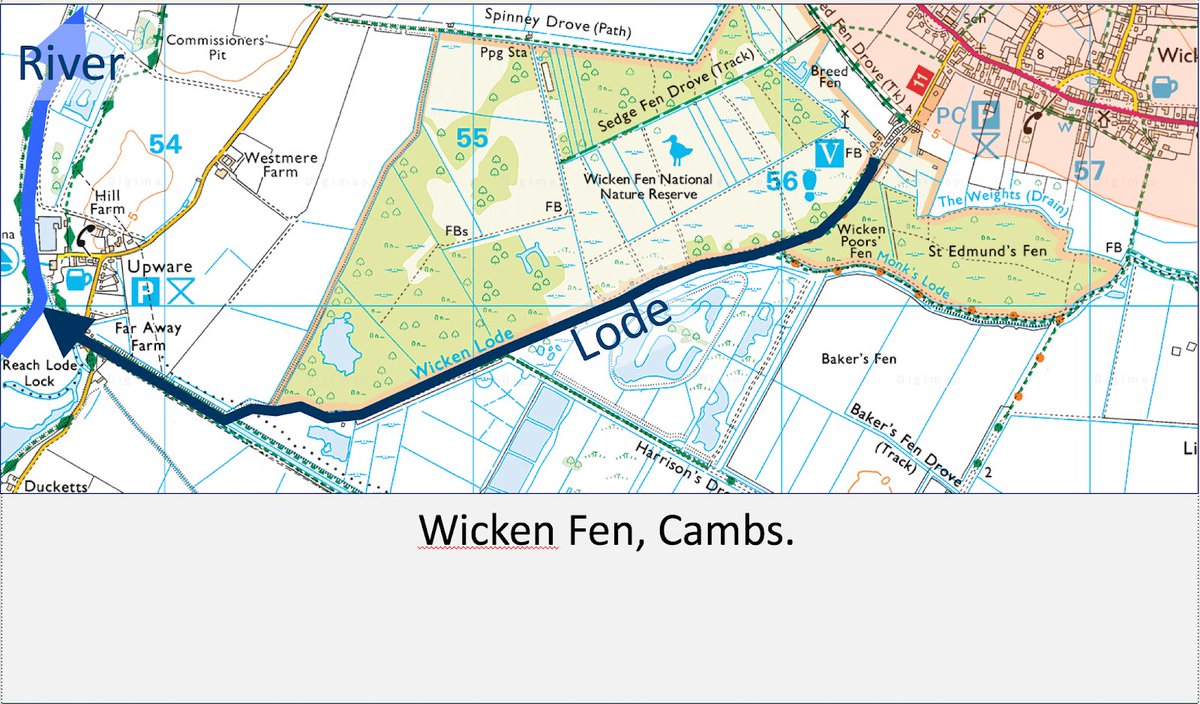

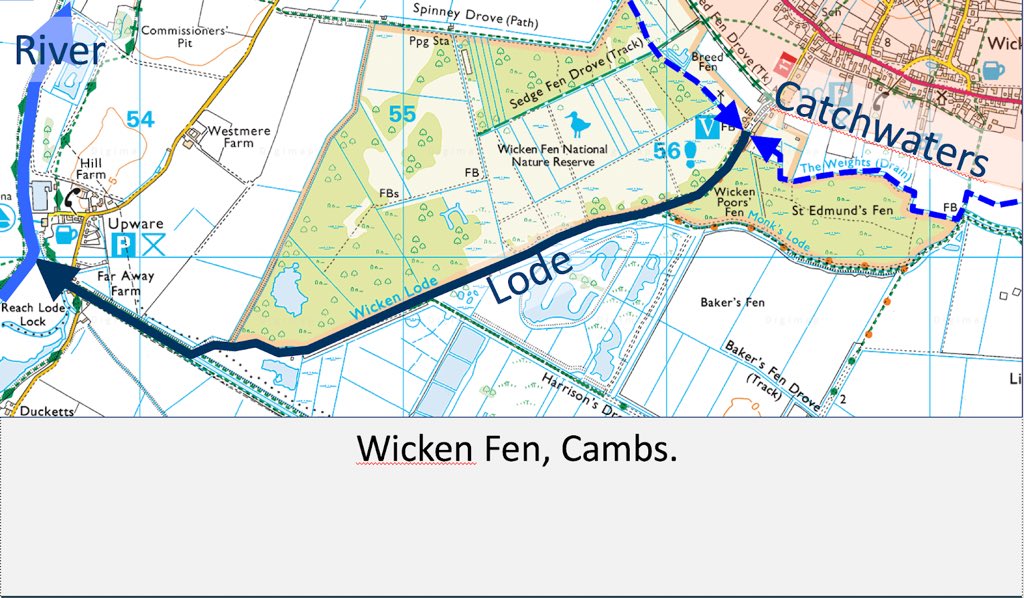

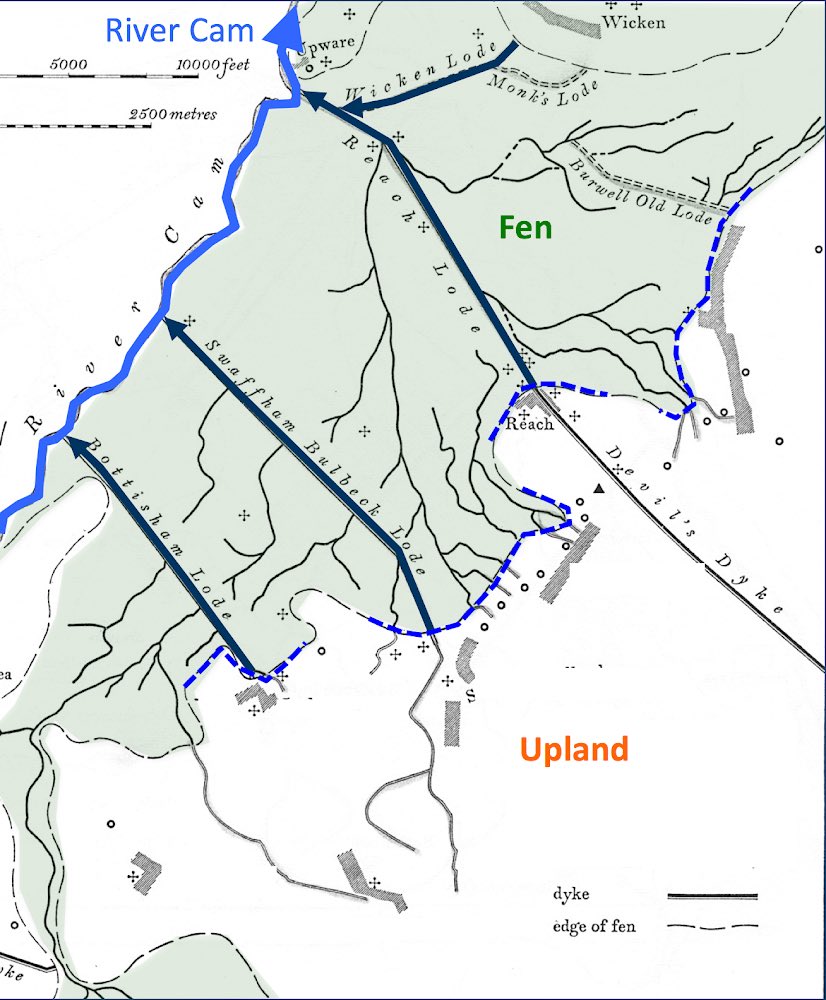

3. Here’s the example of Wicken Lode to illustrate the principles. It runs from the edge of the dry ground (coloured orange, in the top R of the map) to the river Cam on the L. It is fed....

4. ... by two catchwater ditches (dashed blue) which run along the edge of the fen (measured from the highest level of the pre-17thC-drainage winter floods) at +/- 12 ft above sea level. They’re artificial too: they run *along* the contour, not across it from high to lower ground

5. So the role of the catchwaters (like this one at Burwell) is to divert all the water flowing into the fen along streams into the lodes instead. They’re keeping water out of the untrained fen.

6. Short break...

7. The *undrained* fen, darn it - spellchecker has no soul.

8. So, I know you’ve seen this photo of Reach Lode before. See how the lode is embanked? Why build the banks? They’re not essential to keep the water in the lode as the Dutch polder landscape on the R shows ( https://www.collectiefnhz.nl/amstelland/ronde-hoep).">https://www.collectiefnhz.nl/amstellan... I think it is to keep water out of the fen.

9. And have another look at the catchwater (actually, it’s Reach, not Burwell #blush): the high ground with the villageis on the L and the fen on the R - on the other side of that *massive* bank. It has to be big enough to keep the catchwater in place, it’s true. But ...

10. .. a little way further up the catchwater (less undergrowth) you can see there’s no bank on its landward side. What a contrast with the huge bank on its fenward side. The people who built it really minded if the fen flooded, but didn’t mind so much if their properties did..

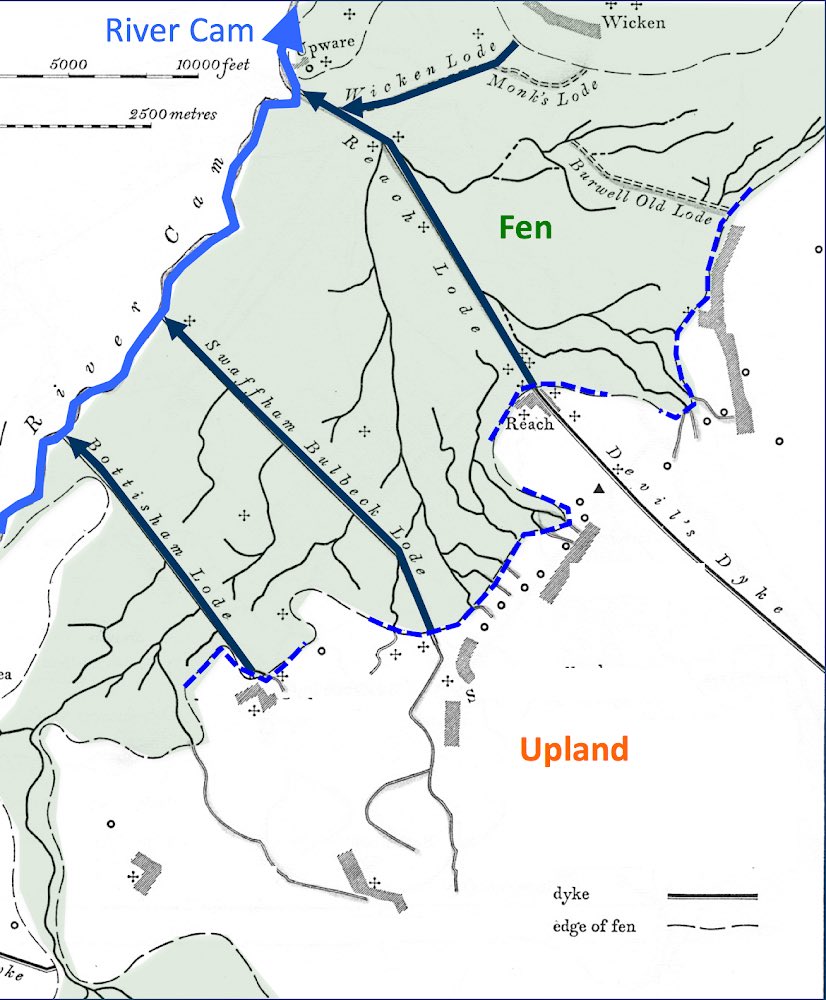

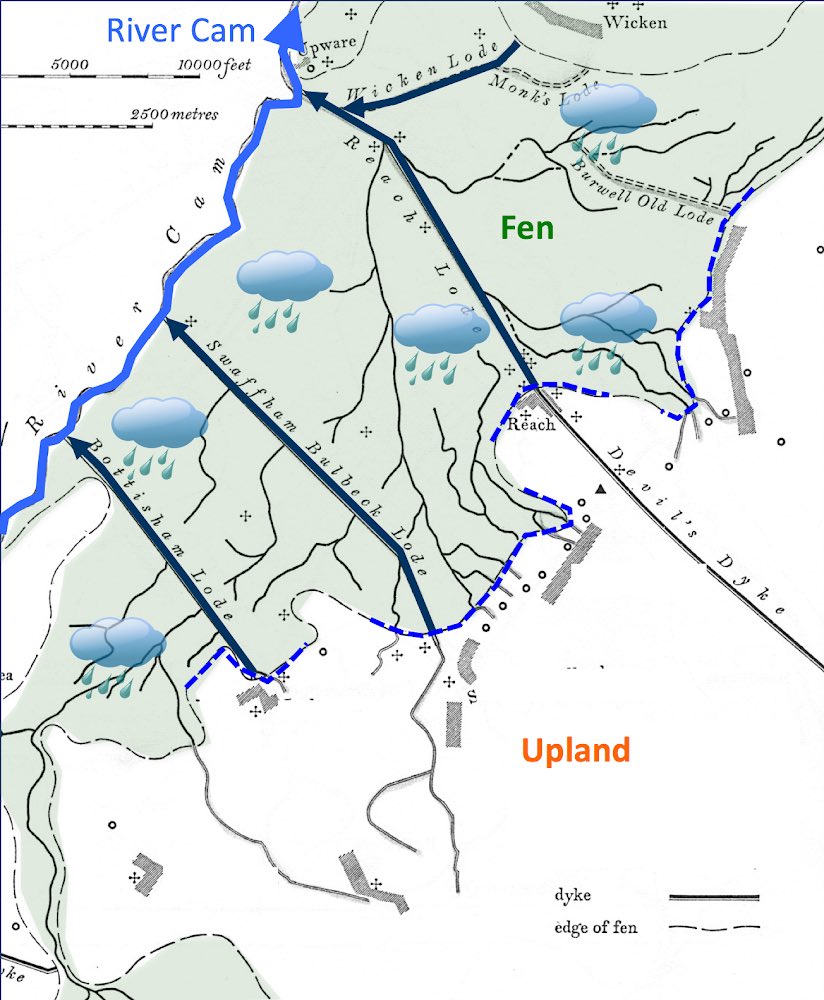

11. The thing is, all that effort to get upland water into the lodes cd only do so much to stop the fen from flooding. Fen (green on the map) = land below 12ft above sea level that flooded regularly every winter.. and there were 2 reasons for that...

12. Reason 1: Rainfall & groundwater still had the potential to flood the fen - they bypassed the catchwaters;

13. And Reason 2: the lodes cut across the natural drainage of the fen whose little streams and creeks couldn’t now take the water that collected there into the river. So...

14. ... fenmen dug ditches - not many, just enough - to carry the water collecting in the fen into the catchwaters or the lodes. The whole system is one of structured water management - but not for drainage.

15. Water levels that sustained the species-rich dairy pastures, reed beds, sedge crops, hay & fodder fens, wildfowl & fish, needed careful management to ensure maximum productivity & long-term sustainability. This was not a drained, but a water-managed, landscape.

16. Here, simply for illustration, are some of those fen ditches just NE of Ely. I love it that there’s still enough peat here for the telephone poles to lean for lack of proper support.

17. There’s so much fun in unravelling how a landscape was used - & the principal source, the landscape itself, is just there, waiting for your attention. Of course there’s always more to do w/ bks, maps etc. But what a great way to spend an hour or 2 out of doors.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😝" title="Squinting face with tongue" aria-label="Emoji: Squinting face with tongue"> END

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😝" title="Squinting face with tongue" aria-label="Emoji: Squinting face with tongue"> END

PS and for armchair exploration out of the heat, see https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol2,">https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cam... especially the fabulous section of fen drainage in the Sectional Preface, written by England’s greatest landscape historian, Christopher Taylor.

And explained in the context of early medieval landscape management here https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Down pointing backhand index" aria-label="Emoji: Down pointing backhand index">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Down pointing backhand index" aria-label="Emoji: Down pointing backhand index">

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

END" title="17. There’s so much fun in unravelling how a landscape was used - & the principal source, the landscape itself, is just there, waiting for your attention. Of course there’s always more to do w/ bks, maps etc. But what a great way to spend an hour or 2 out of doors. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😝" title="Squinting face with tongue" aria-label="Emoji: Squinting face with tongue"> END" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

END" title="17. There’s so much fun in unravelling how a landscape was used - & the principal source, the landscape itself, is just there, waiting for your attention. Of course there’s always more to do w/ bks, maps etc. But what a great way to spend an hour or 2 out of doors. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😝" title="Squinting face with tongue" aria-label="Emoji: Squinting face with tongue"> END" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="And explained in the context of early medieval landscape management herehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Down pointing backhand index" aria-label="Emoji: Down pointing backhand index">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="And explained in the context of early medieval landscape management herehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👇" title="Down pointing backhand index" aria-label="Emoji: Down pointing backhand index">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>