The physicist Maria Goeppert Mayer was born #OTD in 1906. She developed the nuclear shell model of the nucleus, for which she was awarded the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Image: APS

Image: APS

Maria Goeppert Mayer and her husband, a US-born physical chemist, moved to Maryland in 1930. He landed a job at Johns Hopkins. But JH had strict rules about hiring spouses, so she taught without pay. These anti-nepotism rules were mostly used to keep women off the faculty.

Her husband was fired by JH in 1937. He was sure that it was because one of the deans, known for his misogynistic views about women in the sciences, was upset by Maria& #39;s presence in the lab. He took a position at Columbia in NYC, where Maria got a place to work but no pay.

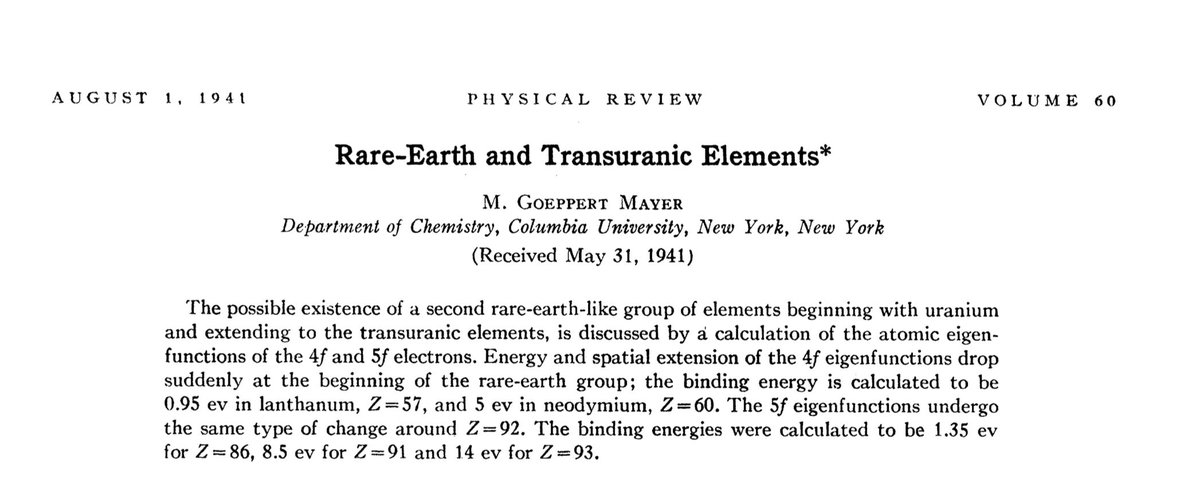

Maria Goeppert Mayer met Enrico Fermi in 1939. He had just arrived at Columbia. Their work had a great deal of overlap, and he suggested that Maria try to sort out the valence-shell structure of the at-the-time hypothetical transuranium elements.

She was remarkably successful. As a former student of Max Born, Maria had a strong command of quantum mechanics. Applying the Fermi-Thomas model of electronic structure, she concluded that the transuranium elements would form a second rare-earth series.

https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10.1103/PhysRev.60.184">https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10...

https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10.1103/PhysRev.60.184">https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10...

In 1942, Fermi& #39;s colleague Harold Urey offered Maria a part-time position in a group he was putting together to look into methods for separating ²³⁵U from natural uranium. This was of course related to the Manhattan Project.

Next, Edward Teller recruited her to take part in the "Opacity Project" at Columbia. This was also connected to the Manhattan Project -- they would study the properties of matter and radiation at the extreme high temperatures associated with a thermonuclear weapon.

Maria considered Teller to be (according to R.G. Sachs) "one of the world& #39;s most stimulating collaborators." She would later work with him on the origins and abundances of elements -- this will prove to be important.

Before long, everyone moved to the University of Chicago. Her husband got a position there as a professor of physical chemistry, and once again anti-nepotism rules left Maria without a paid position She became a "volunteer associate professor."

(It is worth taking a moment to appreciate the horrible euphemistic grandeur of "volunteer associate professor.")

Soon, though, she was hired as a consultant to the Metallurgical Laboratory, where she continued her work with the Manhattan Project and supervised some of the Columbia grad students who had transferred to U Chicago.

The Metallurgical Laboratory was disbanded after the war. Argonne National Laboratory ( @argonne), under the direction of the new Atomic Energy Commission, took its place. Maria became a senior scientist in the Physics Division, where she could pursue nuclear physics full-time.

At Argonne, Maria Goeppert Mayer finally had the opportunity to focus exclusively on her research. It was during this time that she would develop the nuclear shell model.

She was very involved in @UChicago& #39;s Institute for Nuclear Studies, where she joined other luminaries like Teller, Fermi, Urey, and Chandrasekhar to pursue applications of nuclear physics across multiple sub-fields of physics.

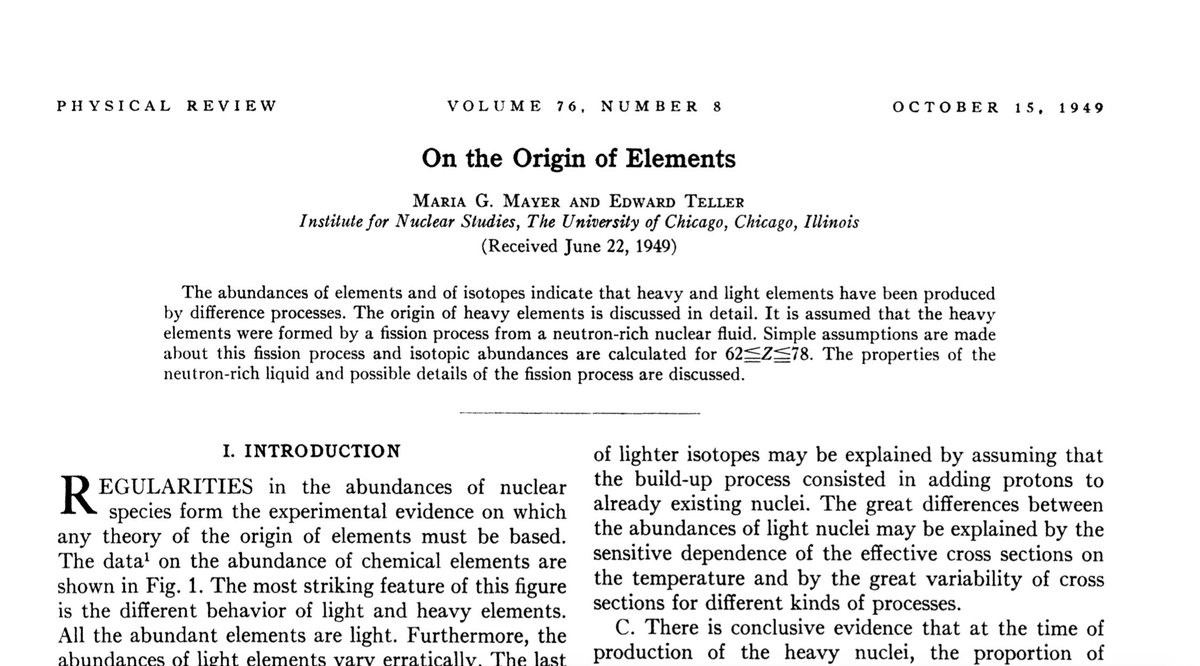

In particular, Maria Goeppert Mayer and Edward Teller began to work on cosmological models of the origins and abundances of the elements.

https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10.1103/PhysRev.76.1226">https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10...

https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10.1103/PhysRev.76.1226">https://journals.aps.org/pr/pdf/10...

During this work, Maria noticed a pattern: elements with certain numbers of protons and neutrons seemed to have higher abundances, as if those configurations were especially stable. The pattern appeared in other properties of the elements, like binding energy and magnetic moment.

A similar observation had been made by Walter Elsasser in 1933, but he had limited data.

It was Eugene Wigner who coined the term "magic numbers" for Maria& #39;s pattern: Atoms with 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, and 126 nucleons are special. This seemed a bit like magic to him, since it didn& #39;t fit the prevailing liquid drop model of the nucleus. Hence the name.

From Maria& #39;s point of view, the pattern was reminiscent of the electronic shell structure that explains the chemical properties of atoms. She set about trying to work out a quantum mechanical explanation for ~nuclear~ shell structure.

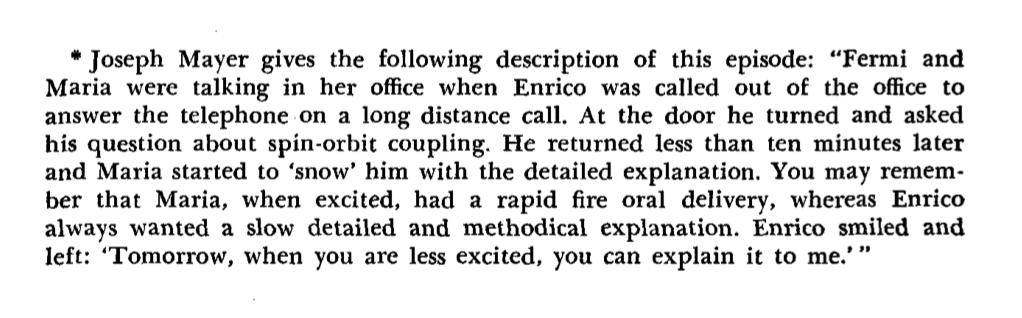

She would frequently stop by Fermi& #39;s office to bounce ideas off him as she worked on this. And it was a question he posed that prompted her key insight. There& #39;s a *great* anecdote here.

Fermi stepped out of his office to take a phone call, and as he walked out he turned and asked "Is there any indication of spin-orbit coupling?" He returned 10 minutes later, and Maria had already worked out many of the details of her spin-orbit coupling shell model of nuclei.

Here is her husband Joseph& #39;s version of the story, as told by Maria Goeppert Mayer& #39;s student and collaborator R. G. Sachs.

Source: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mayer-maria.pdf">https://www.nasonline.org/publicati...

Source: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mayer-maria.pdf">https://www.nasonline.org/publicati...

In Maria Goeppert Mayer& #39;s model, each sort of nucleon – protons and neutrons – fills out shells similar to the electron shells you learned about in chemistry. The Pauli Exclusion Principle limits the number that can fit in a particular shell.

As each shell fills, you find a particular stable nucleus. That is, the binding energy for the next nucleon you try to add is much lower than the one that filled out the last shell.

Maria wrote up her model and submitted it to Physical Review Letters in February of 1949. She then learned that another group of physicists was developing a different model. As a courtesy, she asked the PRL editor to hold her paper so both models could appear in the same issue.

"On Closed Shells in Nuclei. II," presented as a follow-up to her earlier paper laying out some of the experimental evidence for the magic numbers, appeared in June of 1949.

https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1969">https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstra...

https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1969">https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstra...

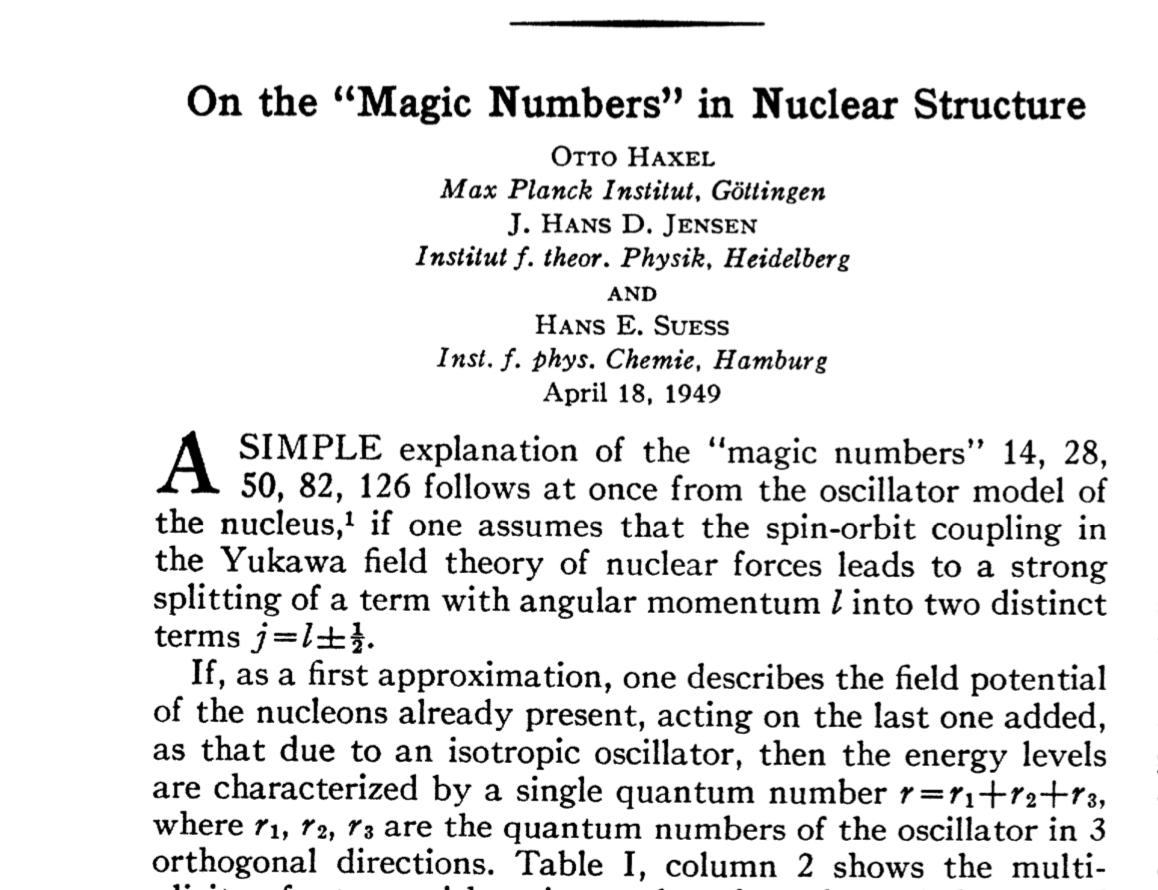

However, because of the delay she requested, Maria Goeppert Mayer& #39;s paper appeared two weeks after a paper by Haxel, Jensen, and Suess that offered a near-identical explanation!

https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1766.2">https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstra...

https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1766.2">https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstra...

But in physics, it& #39;s the submission date that establishes priority, and @PhysRevLett received Maria Goeppert Mayer& #39;s paper more than two months before the manuscript by Haxel, Jensen, and Suess. There was no question who was first.

Maria met Hans Jensen a few years later, in 1951, and they became great friends and close collaborators. In 1955 they published the book "Elementary Theory of Nuclear Shell Structure."

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.177083/page/n3">https://archive.org/details/i...

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.177083/page/n3">https://archive.org/details/i...

In 1956, Maria Goeppert Mayer was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Many of the details in this thread are taken from the NAS biographical memoir prepared by R.G. Sachs.

http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mayer-maria.pdf">https://www.nasonline.org/publicati...

http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mayer-maria.pdf">https://www.nasonline.org/publicati...

And in 1963, Maria Goeppert Mayer shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Hans Jensen and Eugene Wigner.

Maria Goeppert Mayer was just the second woman to overcome the Nobel Physics Committee& #39;s sexism barrier. It had been 60 years since the first woman, Marie Curie in 1903, and it would be another 55 years before the third, Donna Strickland in 2018.

The vibrant Chicago group began to fall apart after Fermi& #39;s death in 1954, and in 1960 Maria and her husband Joseph took positions at the University of California San Diego.

If you ever visit @argonne, look for the plaque outside the physics building celebrating Maria Goeppert Mayer& #39;s work on the nuclear shell model.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/argonne/8167941302">https://www.flickr.com/photos/ar...

https://www.flickr.com/photos/argonne/8167941302">https://www.flickr.com/photos/ar...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter