For various reasons I’ve been thinking a lot about Victorian charity voting recently. (Bear with me…)

Fascinating bit of UK philanthropy history in its own right, but may point to some deeper truths relevant to modern context.

So, please excuse a FRIDAY THREAD (1/)

Fascinating bit of UK philanthropy history in its own right, but may point to some deeper truths relevant to modern context.

So, please excuse a FRIDAY THREAD (1/)

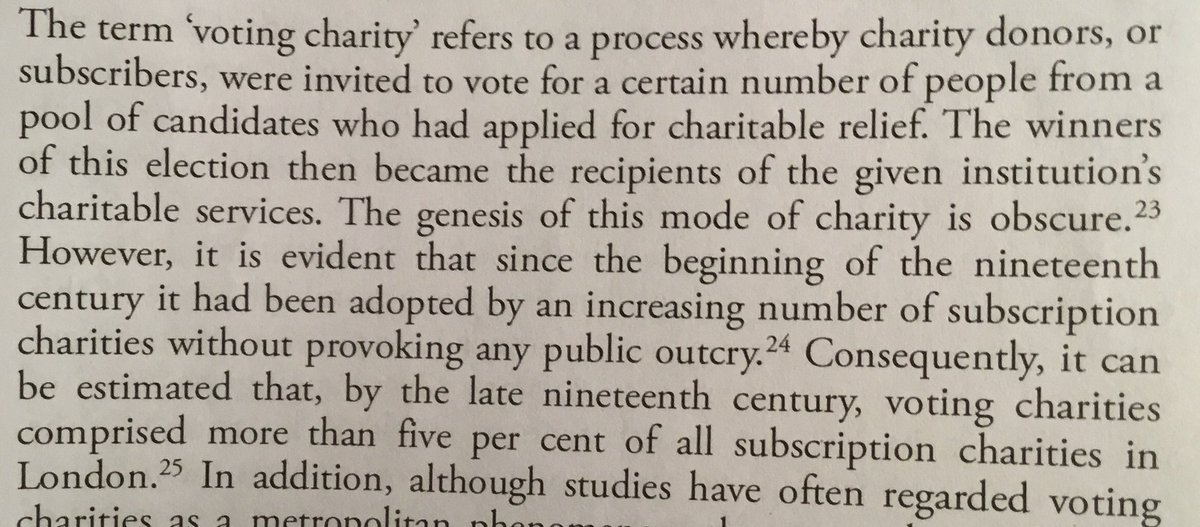

First off, what was Charity Voting, you may ask?

Well, basically it was a form of fundraising where donors (or ‘subscribers’) got to choose who the individual recipients of the charity’s work should be.

No, really: (2/)

Well, basically it was a form of fundraising where donors (or ‘subscribers’) got to choose who the individual recipients of the charity’s work should be.

No, really: (2/)

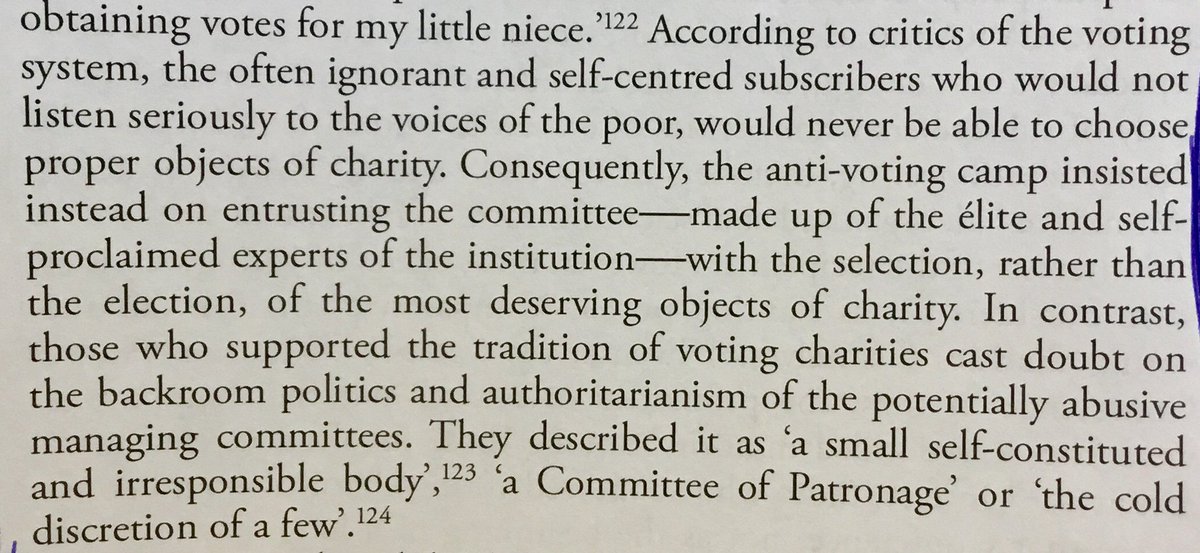

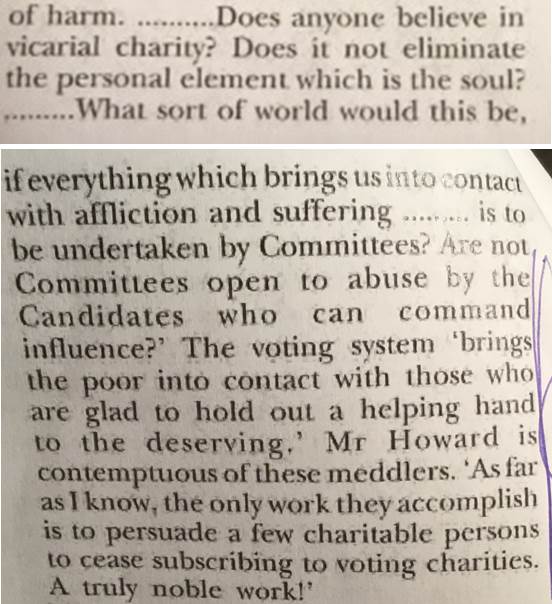

Proponents of Charity Voting generally argued that it was preferable to a reliance on professionalised committees of experts, which they believed took the heart out of charity. (3/)

They REALLY didn& #39;t like the thought of & #39;experts& #39; telling them what to do...

Exhibit B: (4/)

Exhibit B: (4/)

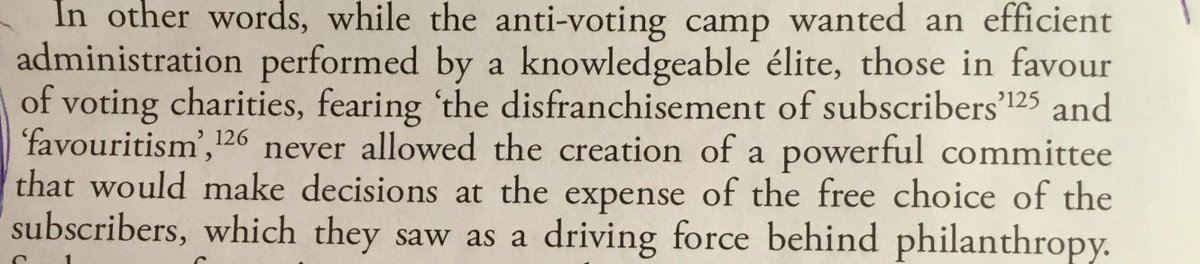

So in terms of the balance between prioritising philanthropic freedom (based on concerns about liberty) and prioritising rationality (based on evidence of what actually works) they were firmly in the former camp:(5/)

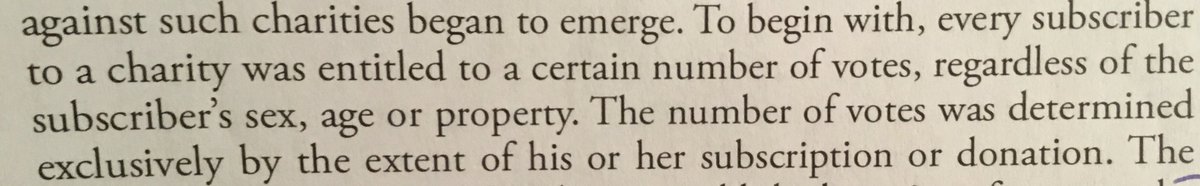

Now, in some ways, charity voting was super progressive (for the donors, at least), as it was one of the only places where women could vote for anything at that time. The only qualifying criteria was cold, hard cash, so: (6/)

Wow, I hear you say - it& #39;s cool that the the men were down with this! Victorian feminism in action!

But of course, they weren& #39;t.

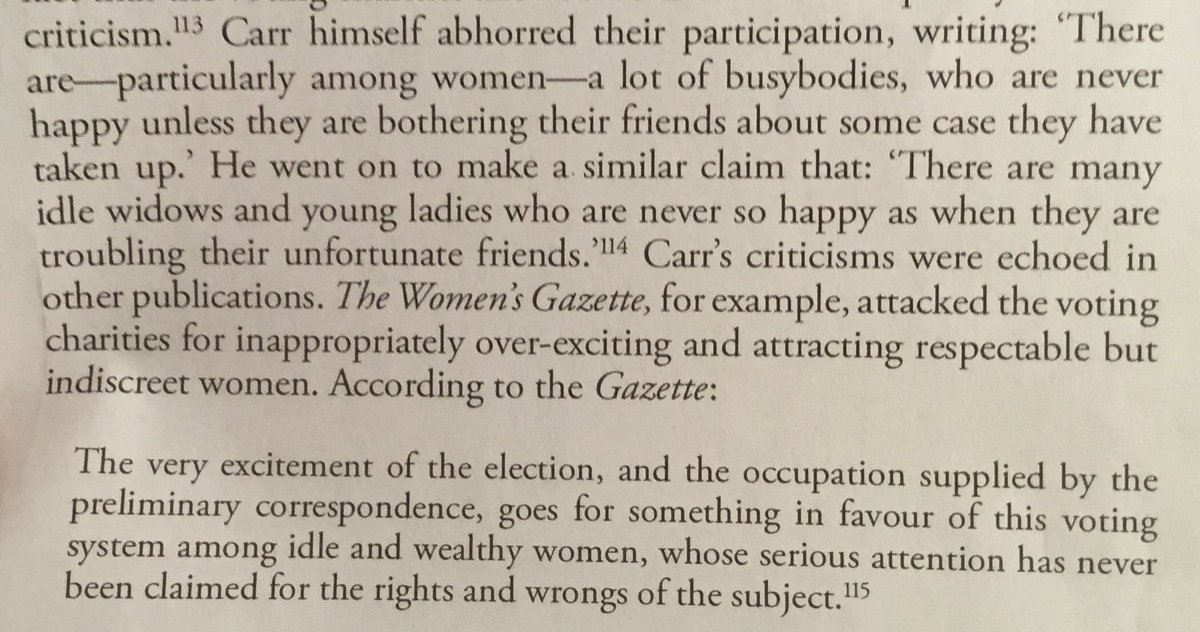

They decried the involvement of women, and tried to blame them for sullying the good name of Charity Voting by taking things too far. (7/)

But of course, they weren& #39;t.

They decried the involvement of women, and tried to blame them for sullying the good name of Charity Voting by taking things too far. (7/)

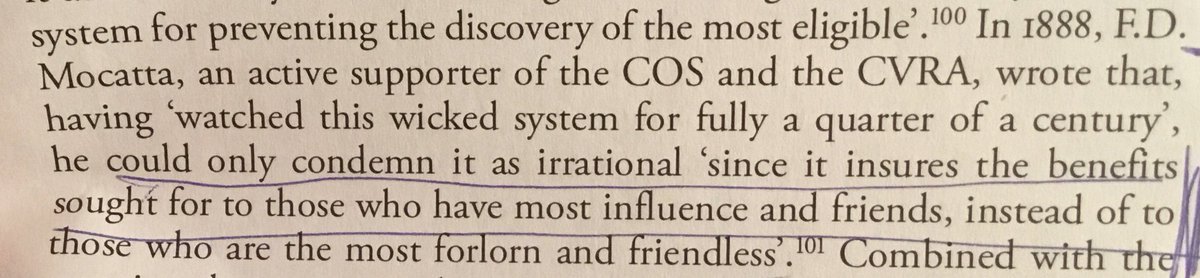

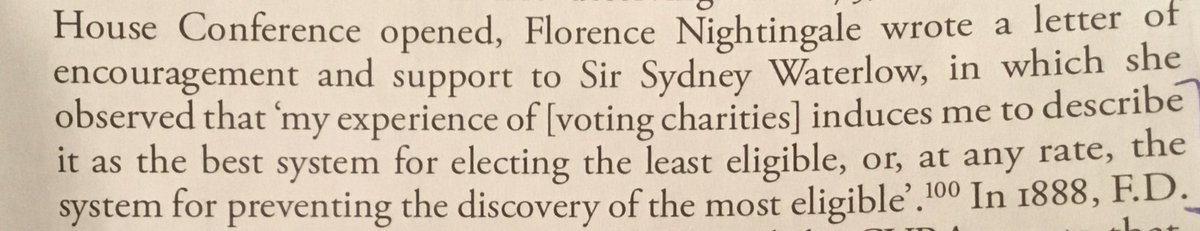

Critics of Charity Voting, meanwhile, argued it was a terrible way of choosing recipients of charity as it was based on uninformed prejudices and emotional responses & rewarded people based on their ability to cultivate well-placed friends rather than on their need: (8/)

Or, as Florence Nightingale put it, it was "The best system for choosing the least eligible."

(And one has to assume she did some sort of Victorian mic drop after deploying this particular burn https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎤" title="Mikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Mikrofon">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎤" title="Mikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Mikrofon"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)

(And one has to assume she did some sort of Victorian mic drop after deploying this particular burn

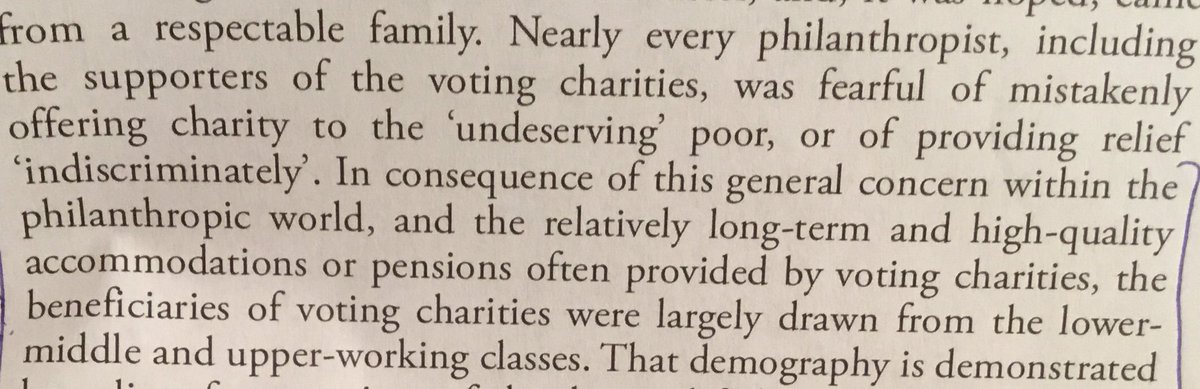

Another problem was that the usual Victorian fear of not accidentally giving to “undeserving” poor people (the horror, the horror!) led many voting charities to play if safe.

To the point where they clearly weren’t helping those most in need: (10/)

To the point where they clearly weren’t helping those most in need: (10/)

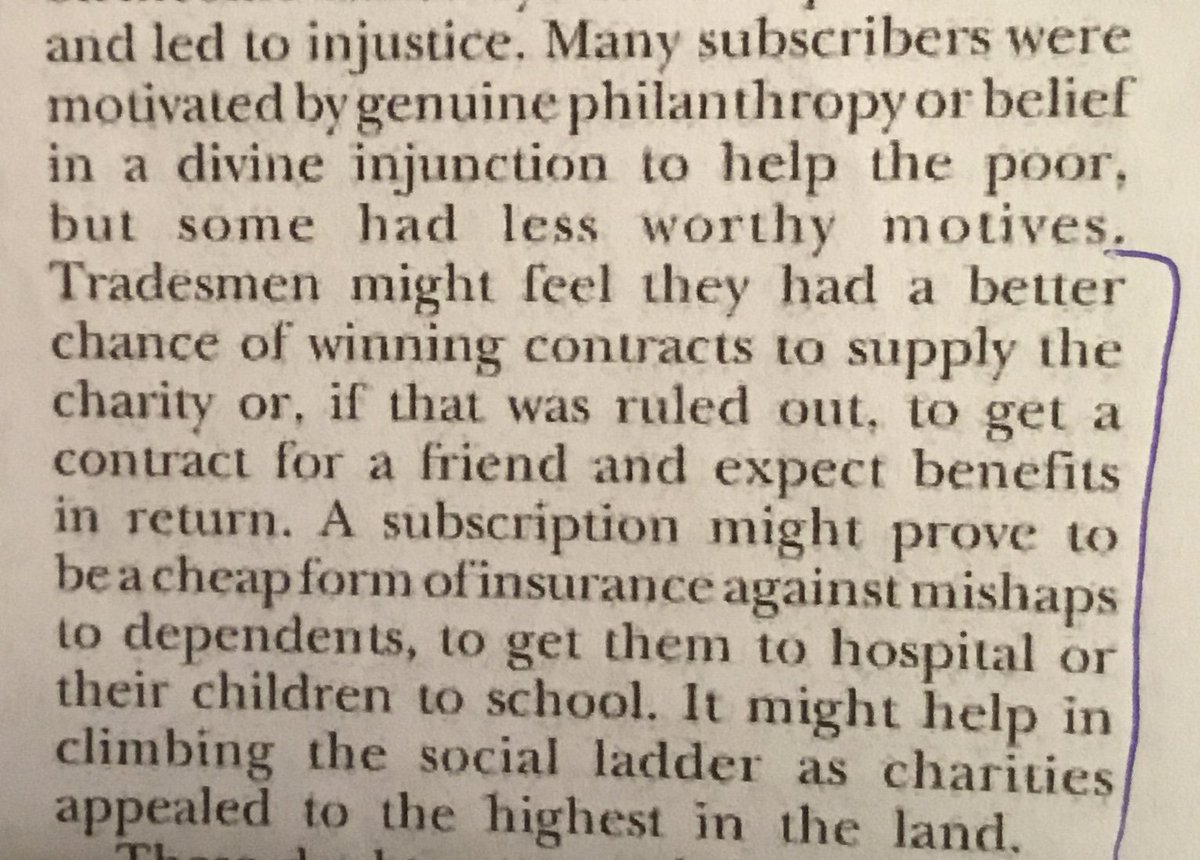

Critics also questioned the motives of donors to Voting Charities.

Some on the grounds of clear and cynical self-interest (11/)

Some on the grounds of clear and cynical self-interest (11/)

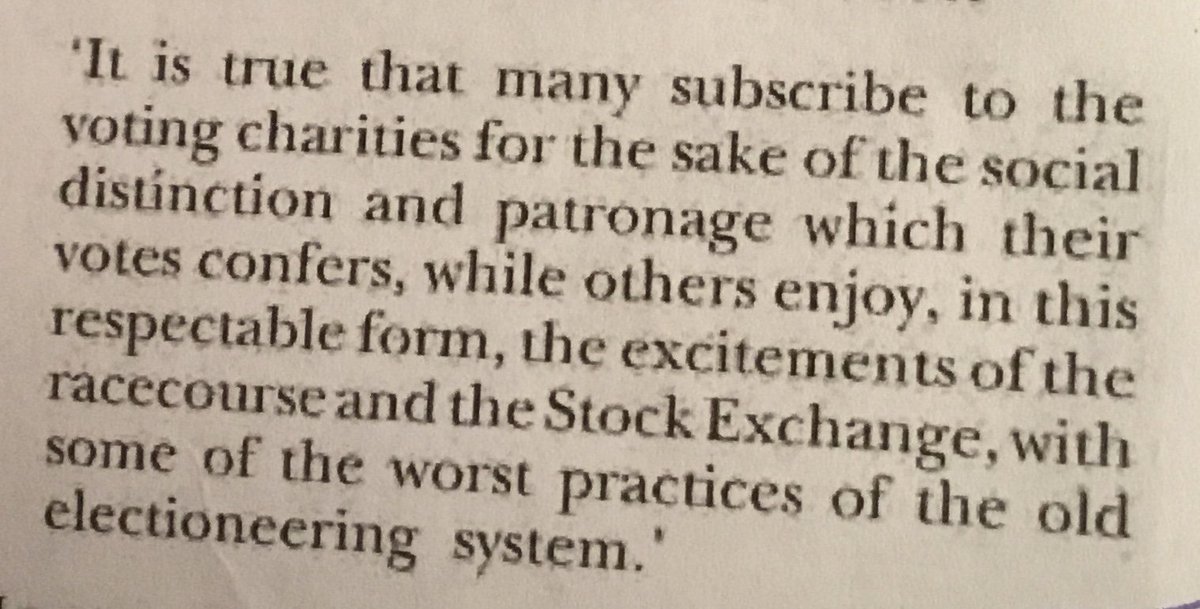

And others on the grounds that donors seemed to be more interested in the voting process itself than the outcomes it delivered: (12/)

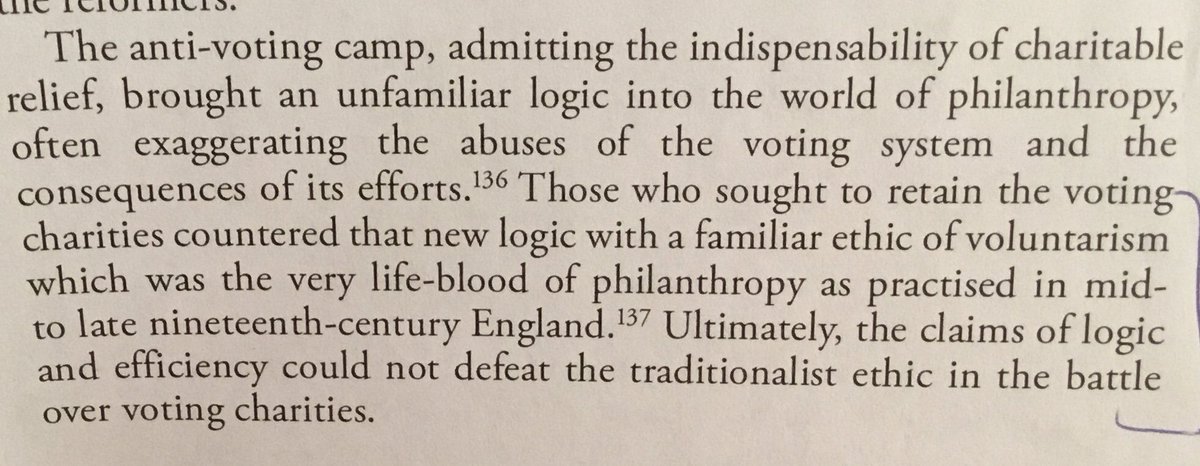

In the end, as with so many other things, this became an argument about head vs. heart in philanthropy. (14/)

And even though it was largely a Victorian phenomenon, it is worth noting that the London Orphan Asylum didn’t stop charity voting until 1951! (15/)

So what’s the modern relevance of all this, you may ask?

Well, as we see the rise of tech-enabled disintermediation within the charity sector, will the qn of the value of expert orgs vs individual choices come to fore once again? (16/)

Well, as we see the rise of tech-enabled disintermediation within the charity sector, will the qn of the value of expert orgs vs individual choices come to fore once again? (16/)

And as trends like crowdfunding for medical treatment or education continue to grow, will donor discretion once again take centre stage?

Could this lead to renewed distinctions between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving cases? (17/)

Could this lead to renewed distinctions between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving cases? (17/)

Might we risk once again rewarding the wrong things (e.g. ability on social media) rather than need?

Discuss… (fin)

Discuss… (fin)

For info: all quotes taken from Kanazawa (2016). “’To Vote or not to Vote’: Charity Voting & the Other Side of Subscriber Democracy in Victorian England” ( https://academic.oup.com/ehr/article-abstract/131/549/353/2450349">https://academic.oup.com/ehr/artic... ) and Alvey (1991) “The Great Voting Charities of the Metropolis” ( https://www.balh.org.uk/publications/local-historian/the-local-historian-volume-21-number-4-november-1991)">https://www.balh.org.uk/publicati...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)" title="Or, as Florence Nightingale put it, it was "The best system for choosing the least eligible."(And one has to assume she did some sort of Victorian mic drop after deploying this particular burn https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎤" title="Mikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Mikrofon">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)" title="Or, as Florence Nightingale put it, it was "The best system for choosing the least eligible."(And one has to assume she did some sort of Victorian mic drop after deploying this particular burn https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🎤" title="Mikrofon" aria-label="Emoji: Mikrofon">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔥" title="Feuer" aria-label="Emoji: Feuer">): (9/)" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>