Thread: Economic Naturalist Question #7. Why might an appliance retailer hammer dents into the sides of its stoves and refrigerators?

In an earlier thread, I explored why introductory economics courses appear to leave little lasting imprint on the millions of students who take them each year: https://twitter.com/econnaturalist/status/1091461433487953924">https://twitter.com/econnatur...

Students learn more effectively when they pose interesting questions based on personal experience, and then use basic economic principles to help answer them. This exercise became what I call my “economic naturalist” writing assignment.

Some of my students& #39; best questions have dealt with how firms set prices. Sellers might like to charge the highest price each customer is willing to pay. But the possibility of resale among consumers limits their ability to do that.

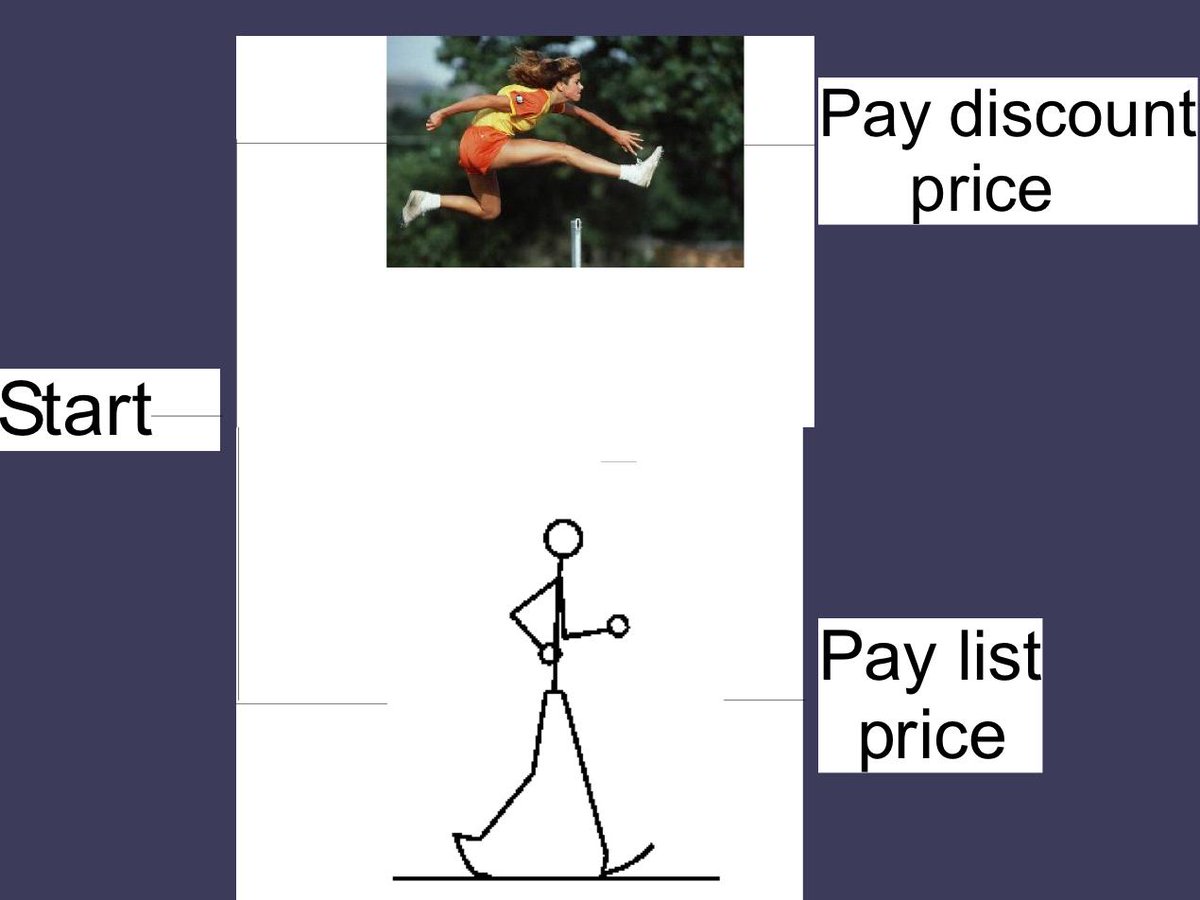

Many sellers have developed ingenious ways of getting around this constraint. Their tactics often share a common feature: the seller permits the buyer to purchase at a discount, but only after jumping a hurdle of some sort.

One common hurdle is the temporary sale. Buyers can obtain a discount by taking the trouble to learn when the sale takes place and showing up to buy during that window. Those who are unwilling to take those steps pay the higher list price.

A vivid example in this vein begins with the observation that a small fraction of appliances sustain minor cosmetic damage when shipped from manufacturers to retailers.

Rather than ship these appliances back to the factory for repair, retailers discovered that it was simpler just to sell them at discount prices. Sears was an early champion of the scratch-’n’-dent appliance sale.

Reports began to circulate, however, that in the days leading up to the sale, Sears had warehouse employees hammering dents into the sides of otherwise unblemished appliances. Were these reports just another urban legend?

Or might a profit-seeking retailer have had sound economic reasons for deliberately damaging some of its merchandise?

Sellers want to give discounts to only those buyers who wouldn’t purchase at list price. They may have discovered by accident that a slightly blemished refrigerator is an excellent hurdle for segregating potential buyers in this way.

A scratch-’n’-dent sale buyer must actually clear three hurdles at once: 1. Find out when the sale occurs; 2. Show up on that particular day; and 3. Tolerate the refrigerator& #39;s blemish, even if it will not be visible once the machine is installed.

Few high rollers would be willing to jump even one of these hurdles. But as Sears quickly discovered, substantial numbers of price-sensitive shoppers were happy to clear all three. The earliest scratch-& #39;n& #39;-dent sales always sold out quickly.

It is thus by no means far-fetched to imagine that an appliance retailer possessing a limited supply of appliances damaged in transit might find it profitable to send an employee with a hammer out to the warehouse on the day before the annual scratch-’n’-dent sale.

Such practices are sometimes called price discrimination, a term that encourages us to think of them as a bad thing.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter