I wrote about D.C. statehood. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/democrats-push-to-make-washington-dc-the-fifty-first-state">https://www.newyorker.com/news/news...

Over the course of writing and telling people about this piece, I& #39;ve often been asked why D.C. isn& #39;t a state in the first place. A very condensed, yet still very long answer to this question might begin with a hot June day in Philadelphia back in 1783.

Congress, then meeting in Philadelphia’s State House, had been struggling to pay soldiers as the Revolutionary War ended. On June 19, John Dickinson, effectively Pennsylvania’s governor, delivered them some alarming news.

A group of furloughed troops was marching towards the city to, according to a letter, “procure their pay (or perhaps to possess themselves of money at any rate.)” This was a threat. (“Reinterpreting the "Very Trifling Mutiny" at Philadelphia in June 1783,” Mary Gallagher)

When Congress asked Dickinson to deploy the state’s militia in its defense, he refused, arguing that the soldiers had yet to cause any real trouble. The soldiers entered the city the next day and entered into negotiations with a group of intermediaries led by Alexander Hamilton.

By the morning of June 21st, talks had stalled and the soldiers began surrounding the State House. It was hot, they were drinking, and they were armed.

As legislators left the building and walked through the mob of soldiers to go home at the end of the day, a group of mutineers egged on by spectators briefly captured and released the president of Congress, Elias Boudinot.

Concerned that the situation could escalate further, Congress continued asking Dickinson to deploy the state’s troops to no avail. Eventually, they fled to Princeton, New Jersey, where Congress would remain until November.

After the retreat to Princeton, the capital of the new American republic would change three more times -- to Annapolis, Maryland in late 1783, Trenton, New Jersey in 1784, and New York City in 1785 -- before the drafting of the Constitution in 1787.

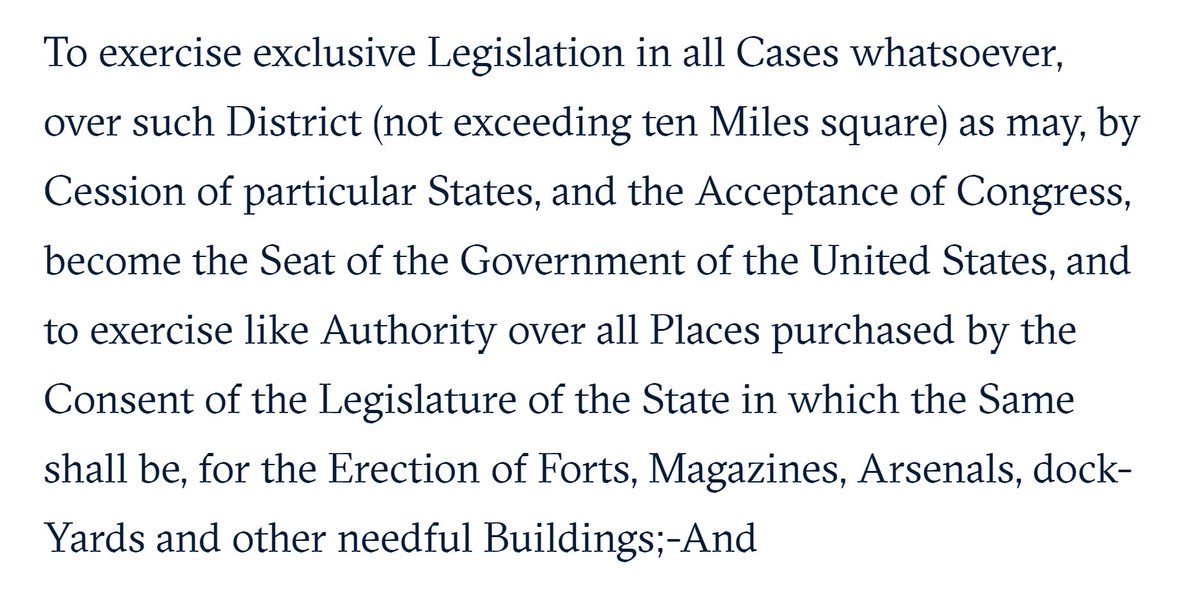

The Framers wrote into Article I a provision establishing an area “not exceeding ten Miles square,” at a location TBD, that would serve as “the Seat of the Government of the United States,” an area where the federal government would “exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases."

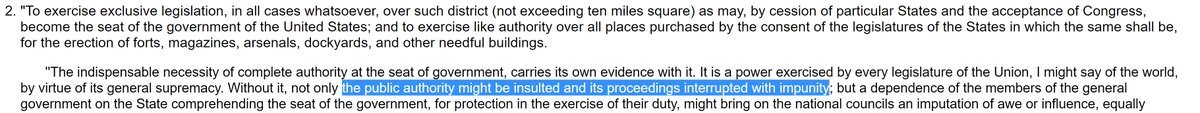

James Madison’s case for the idea in Federalist 43, suggests that the Framers had the events of 1783 in mind. Without “complete authority at the seat of government,” he wrote, ”the public authority might be insulted and its proceedings interrupted with impunity.”

The essay argues too that an independent district would shield the federal government from the undue influence of a state that housed the capital.

In 1790, a district was created from territory along the Potomac ceded by MD and VA -- a site chosen, by legend, as part of a deal to secure the passage of a bill transferring state debts to the federal government brokered between Hamilton & Madison over a dinner at Jefferson’s.

The two large pre-existing settlements within the district, the towns of Alexandria and Georgetown, and a new county, Washington were allowed by Congress to retain municipal governments.

This would have been an tidy solution were it not for the fact that the area was home to thousands of former MD and VA citizens who, with the official transfer of the district to federal control in 1801, lost congressional representation and votes in the Electoral College.

Pockets of residents began complaining almost immediately. In 1801, Augustus Woodward, a wealthy and eccentric landowner who would later become Chief Justice of Michigan’s Supreme Court and a co-founder of UMich, authored a pamphlet decrying their disenfranchisement.

I’m fast-forwarding 160 years now. Some interesting Reconstruction-era bits in that interval -- look up the Organic Act of 1871-- but things really pick up on the status question in 1961.

That year, after decades of on and off griping about D.C.’s predicament, Congress passed the 23rd Amendment, which granted residents the right to vote in presidential elections & as many Electoral College votes as the least populous state. (D.C. was more populous than 11 states.)

In 1960, both Kennedy and Nixon backed the amendment, which was easily passed -- in the House the amendment was advanced by a voice vote-- and ratified by the requisite thirty-eight states in less than a year, faster than the ratification of the 21st, which ended Prohibition.

The 23rd was popular and noncontroversial enough, in fact, that a few states playfully contested the claim to having cinched the amendment’s ratification.

Kansas hurried the legislation through its legislature in an emergency session, beating, as James MacNees of the Baltimore Sun reported, ”Ohio to the wire by forty-two minutes.”

New Hampshire’s legislature, which also ratified the amendment on the same day, annulled and re-ratified it in an attempt to secure its claim to having been the thirty-eighth. The Washington Post:

To date, all but ten states have taken action to ratify the 23rd Amendment. All ten that have not are in the South, including Arkansas, the only state to actually reject the amendment in a vote. I think you can see where this is going. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-third_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twen...

In 1960, the census recorded a majority black population (54%) in Washington for the first time, a figure that was the product of both the Great Migration and the flight of white residents who had comprised over 60% of the population just 10 years earlier. The NYT on the 23rd:

At the time, Southerners controlled the House’s committee overseeing district affairs, led by chairman John McMillan of South Carolina.

When Washington submitted the city’s first independently written budget to Congress in 1967, McMillan responded by sending Walter Washington, the city’s first appointed mayor and an African-American, a truckload of watermelons. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/after-bloodshed-in-earlier-us-riots-dc-police-showed-restraint-in-1968-unrest/2018/03/23/eec41d0a-2624-11e8-bc72-077aa4dab9ef_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.d7f8aa35aef3">https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/aft...

Predictably, debates over the city’s status became increasingly entwined with the civil rights movement. In 1968, Congress granted DC an elected school board, to the relief of judges eager to wash their hands of the controversy over de facto segregation in DC schools.

This was followed by the reinstatement of the district’s nonvoting delegate to Congress in 1970. The first was Walter Fauntroy, a civil rights activist and pastor who had helped coordinate the March on Washington. https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/13023">https://history.house.gov/People/De...

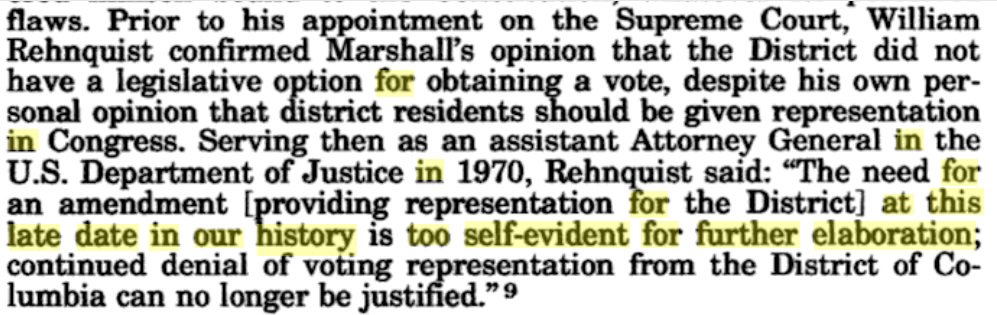

By then, liberals like Ted Kennedy and district advocates had begun pushing a constitutional amendment granting D.C. two Senators & a voting congressman. South aside, there was actually broad support for this. Then Assistant Attorney General Rehnquist, a conservative, in 1970:

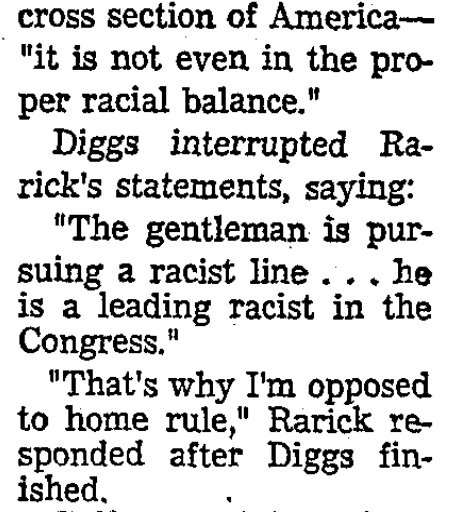

By 1970, DC was over seventy percent black. In an appearance before the House District Committee in 1972, Rep. John Rarick of Louisiana warned that the city would be taken over by black Muslims if granted home rule and argued that DC lacked a “proper racial balance.”

When another Congressman interrupted Rarick to remark that he was “a leading racist in the Congress,” Rarick’s reply was simple. ”That’s why I’m opposed to home rule,” he said.

Voices like Rarick’s would be chastened as the decade wore on -- the Southern black electorate finally brought into being by civil rights legislation forced many of the region’s legislators antsy about reelection to consider making concessions to the black community.

In a sudden turn, McMillan himself endorsed home rule for the district in in 1972 ahead of a primary he would ultimately lose to a young candidate who did well with black voters in his district.

This softening contributed to the passage of the Home Rule Act in 1973, which granted the district an elected mayor and city council for the first time since 1874.

That momentum carried over into 1978, when Kennedy’s constitutional amendment granting the district two voting senators and a voting congressman *passed*.

Just want to reiterate this: In 1978, Congress passed, on a bipartisan basis, a constitutional amendment granting Washington, D.C. two senators and a voting congressman in the House.

The yes votes included notorious segregationist Strom Thurmond, who spoke out repeatedly in the the district’s favor in the months before the vote. “Human rights,” he said in a floor speech, “begin at home here in the nation’s capital.”

Just to say this again: Anyone opposing full Congressional representation for D.C. in 2019 is to the right of Strom Thurmond in 1978.

The amendment prevailed in Congress despite fear on the right that the district’s senators would be, in Kennedy’s words, ”too liberal, too urban, too black, or too Democratic.” But that fear doomed the amendment’s prospects for ratification.

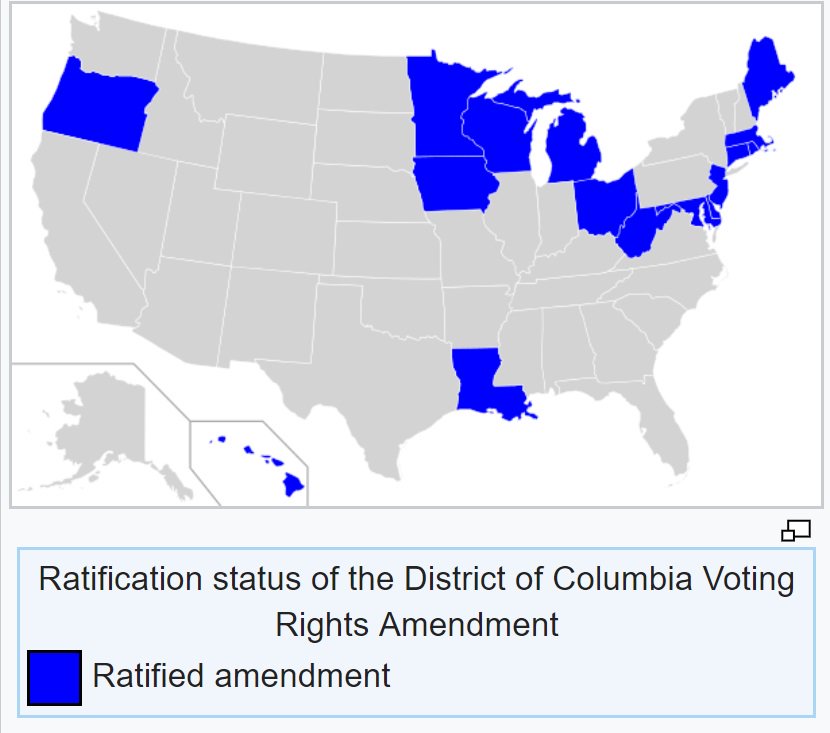

By the time the ratification deadline passed in 1985, only 16 of the required 38 states had passed the amendment. All but three were in the northeast and midwest. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/District_of_Columbia_Voting_Rights_Amendment">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dist...

Full statehood for the district emerged as a serious path to representation and autonomy as the voting rights amendment’s prospects for ratification waned, although it had been pushed on and off for some time.

In 1970, a year after a group of black nationalists created the “D.C. Statehood Committee,” Capital East Gazette editor Sam Smith, one of the city’s prominent New Left activists, made the case for statehood in a piece expressing his cynicism about incrementalism.

To Smith’s point, the Home Rule Act in 1973 granted the district an elected mayor and city council, but left Congress with the power to review and block legislation they passed.

In 1980, voters in DC narrowly passed a statehood initiative that led to the convening of a constitutional convention in 1982.

The constitution of New Columbia not only outlined a framework for governance but also committed the state to a job guarantee and equal pay, protections for LGBT residents, public daycare, a state bank, and other progressive priorities. https://statehood.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/statehood/page_content/attachments/1982-Constitution-for-the-State-of-New-Columbia.pdf">https://statehood.dc.gov/sites/def...

As interest in statehood grew, opposition to granting Washington full voting rights escalated on the right.

After the convention, an editorial in National Review argued that D.C. would “vie with Haiti and Santa Monica as the worst governed jurisdiction in this hemisphere” and warned the constitution’s affirmative action plank was “official approval of reverse discrimination.”

In 1987, former white supremacist and nationally syndicated conservative columnist James Kilpatrick wrote that upon forthcoming debates on the issues in Congress ”the blacks, the homosexuals, the whole shebang will be whooping it up for ‘the state of New Columbia.’”

In 1990, Floyd Brown, founder of Citizens United & Willie Horton ad producer, started Citizens United Against D.C. Statehood. which ran mailers warning DC could produce a Senator “who embraces Arab terrorists” or “Black Muslim hatemongers” and “wants socialism for our economy.”

In the summer of & #39;93, the Washington Post noted that a donor to Citizens United from Arkansas had appended a note expressing his opposition to the creation of “a majority state of so-called minority citizens and soon a trifold presidency -- Clinton, Hillary and [Jesse] Jackson!"

Jackson had by then become a prominent statehood advocate and was instrumental, along with Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton in building support for a statehood vote in Congress in 1993. It tanked, opposed in the final tally not only by House Republicans, but over 100 Democrats.

Things haven’t moved all that much until very recently. Last week, in fact, as I mention in the piece. The passage of HR 1 marks the first time a house of Congress has endorsed statehood. We’ll likely see HR 51 pass soon.

A lot has been made, by people including myself, of the boon statehood would be to advancing a left-wing agenda. But it should be emphasized too that the case for statehood can be made on its own merits.

When President Obama agreed to an amendment barring DC from using its own funds for abortions as part of a deal to avoid a government shutdown in 2011, 28 women scheduled for abortions were told there would be no money for them. https://dcist.com/story/11/04/14/abortion-funding-cut/">https://dcist.com/story/11/...

This is how things work -- Congress, a body in which the District has no voting representation, has the authority to overturn the city’s will. It’s an indefensible situation and we’ve known it forever.

There are constitutional challenges to statehood. For starters, the text of Article I is clear. But statehood bills shrink the district the constitution calls for to an area comprising key federal buildings and make the rest of the city a new state.

If that holds up in an inevitable court battle, that leaves the 23rd Amendment which, given the above solution, would grant the President and whoever else lives in the above district three electoral votes.

This is not ideal, but 1) it seems more like an awkward situation rather than an actual independent constitutional problem to me, and 2) the discretion the 23rd gives Congress regarding D.C.’s electors might offer a workaround.

Anyway, D.C. should be a state.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![In the summer of & #39;93, the Washington Post noted that a donor to Citizens United from Arkansas had appended a note expressing his opposition to the creation of “a majority state of so-called minority citizens and soon a trifold presidency -- Clinton, Hillary and [Jesse] Jackson!" In the summer of & #39;93, the Washington Post noted that a donor to Citizens United from Arkansas had appended a note expressing his opposition to the creation of “a majority state of so-called minority citizens and soon a trifold presidency -- Clinton, Hillary and [Jesse] Jackson!"](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1VLnA3XQAAcl4V.jpg)