PRINCIPLES TO UNDERSTAND OUR MIND:

1) Our mind is an ensemble of parallel, bottom-up processes. It cannot be described as a single top-down process, even if this is how we perceive it.

2) Our mind is not made to perceive correctly, but to act correctly.

1) Our mind is an ensemble of parallel, bottom-up processes. It cannot be described as a single top-down process, even if this is how we perceive it.

2) Our mind is not made to perceive correctly, but to act correctly.

(Corollary to #2: perception biases are features, not bugs.)

3) Perception is proactive. We choose what to sense in order to facilitate action.

(Corollary to #3: one can’t build an *effective* mind whose only job is to perceive. This is a limit of many current AI approaches.)

3) Perception is proactive. We choose what to sense in order to facilitate action.

(Corollary to #3: one can’t build an *effective* mind whose only job is to perceive. This is a limit of many current AI approaches.)

4) Our brain is specialized, not modular, just like our cells are specialized *in their outputs* but their inputs are general (they get info about the general state of the body) and could not live as separate modules.

(Corollary to #4: current AI approaches will fail if they’re kept as modular. Our brain works because most of it receives feedback from most of our actions and reactions; brain modules do not talk *exclusively* through limited bandwidth APIs).

5) Our conscious thoughts are a “simulator app” used by our brain to run bottom-up simulations to predict results it cannot infer with experience-based *direct* inferences alone (aka intuition).

6) As much as an app cannot fully understand the machine it is mounted on, not the processes that called for its execution, so our conscious mind cannot fully understand our unconscious one.

7) Admissibility is our mind’s proxy for truth.

(Admissibility of simulations is our conscious mind’s proxy for their truthfulness.)

8) The admissibility of stories is (also) measured by how well they match our internal emotional state.

(Admissibility of simulations is our conscious mind’s proxy for their truthfulness.)

8) The admissibility of stories is (also) measured by how well they match our internal emotional state.

( #8 explains how we make sense of dreams, why BS stories stick, the adoption curve and many of the emergent behaviors of groups of humans; however irrational it might seem, it makes evolutionary sense. Perhaps one day I’ll write a post about it.)

9) Stories are justifications to explain the mismatch between the 2+ events we observe and our simulation of it; by their property of increasing the admissibility of two observations appearing together, they reduce surprise and improve acceptance of what we perceive.

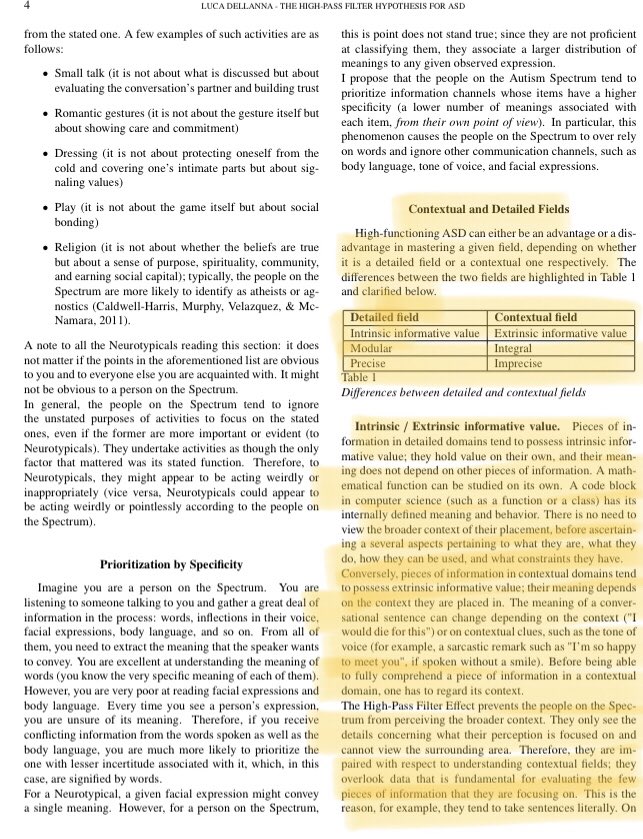

10) The ability of our brain to formulate stories to make sense of what we observe is a critical element of learning. Those who are, on average, less likely to make stories out of incoherent observations are better at detailed (*) fields and impaired at contextual (*) fields

(*): this paper explains the differences between detailed and contextual fields https://psyarxiv.com/xm5ca

As">https://psyarxiv.com/xm5ca&quo... example: computer science and physics are detailed, social conversations are contextual.

(of course, we’re talking about a spectrum and averages here)

As">https://psyarxiv.com/xm5ca&quo... example: computer science and physics are detailed, social conversations are contextual.

(of course, we’re talking about a spectrum and averages here)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter