It& #39;s not well known that the congregation of the First African Baptist Church in Richmond donated approximately $40 towards Irish Famine Relief in 1847. Around 2,000 members of the congregation were slaves, and only 150 were free.

Instead of thanking this impoverished and enslaved community for their generosity, the Irish American Boston Pilot newspaper used this story to mock British philanthropy and essentially argue that it was proof that the Irish had it “worse” than slaves.

Thirteen years later the same newspaper argued that the abolition of slavery would be a terrible mistake as "by overstocking the market of labor [it would] do incalculable injury to white hands.”

Many former slaves in the British West Indies, emancipated in 1834-& #39;38, were also among those who contributed. They donated from what little money they had to spare. A detailed breakdown can be found in Christine Kinealy’s ‘Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland’ (2013)

Meanwhile in the U.S. Senate John Niles declared that “Charity begins at home" as he argued against the U.S. government sending aid to Ireland during the Great Famine.

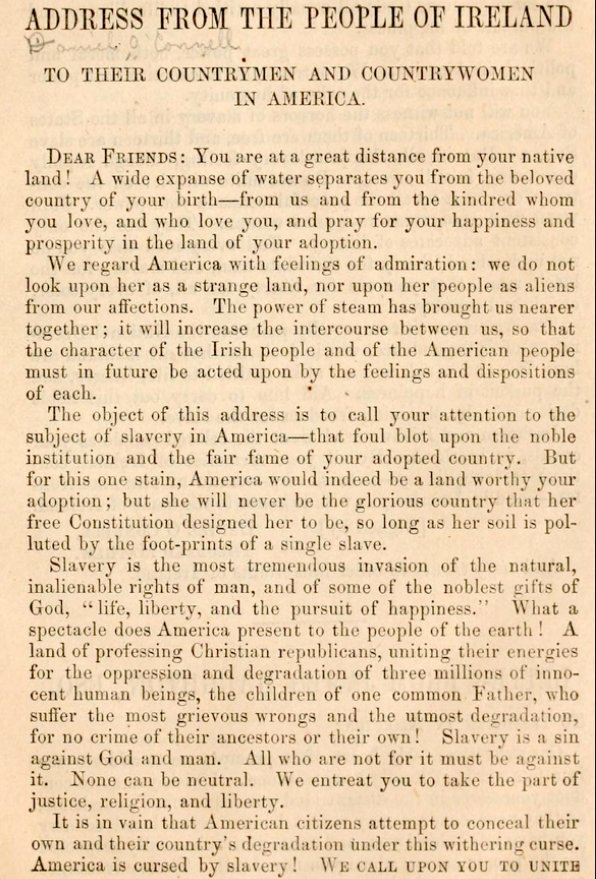

In 1841 approx 60,000 Irish people signed an anti-slavery address composed by the Hibernian Anti-Slavery Society. It was addressed to the Irish American community. "Irishmen and Irishwomen! Treat the colored people as your equals, as brethren."

The Archbishop of New York, John Hughes of Co. Tyrone, rejected the Irish Address and denounced it as a forgery. While the Boston Pilot assured its readers that slaves were actually pro-slavery as "they love their masters, as dogs do..."

The result? After initial enthusiasm when the list of signatures was unrolled at Faneuil Hall (it stretched from the entrance to the podium) Garrison wrote that "not a single Irishman has come forward, either publicly or privately, to express his approval of the Address."

In New York in 1859 Charles O’Conor, an influential Irish American lawyer and the son of a United Irishman, made public statements in favour of racial slavery: "Negro slavery is not unjust...it is just, wise and beneficent...the condition of the negro is assigned by nature."

"He has ample strength and is competent to labour but nature denies him either the intellect to govern or the willingness to work." He was pro-Confederate during the Civil War and served as counsel for Jefferson Davis after it ended.

John Mitchel: "If you are asked & #39;Would you like an Irish Republic with an accompaniment of slave plantations?& #39; answer quite simply, & #39;Yes.& #39;" (1854)

"Re-opening the African Slave trade is a question of expediency alone." (1857)

"Re-opening the African Slave trade is a question of expediency alone." (1857)

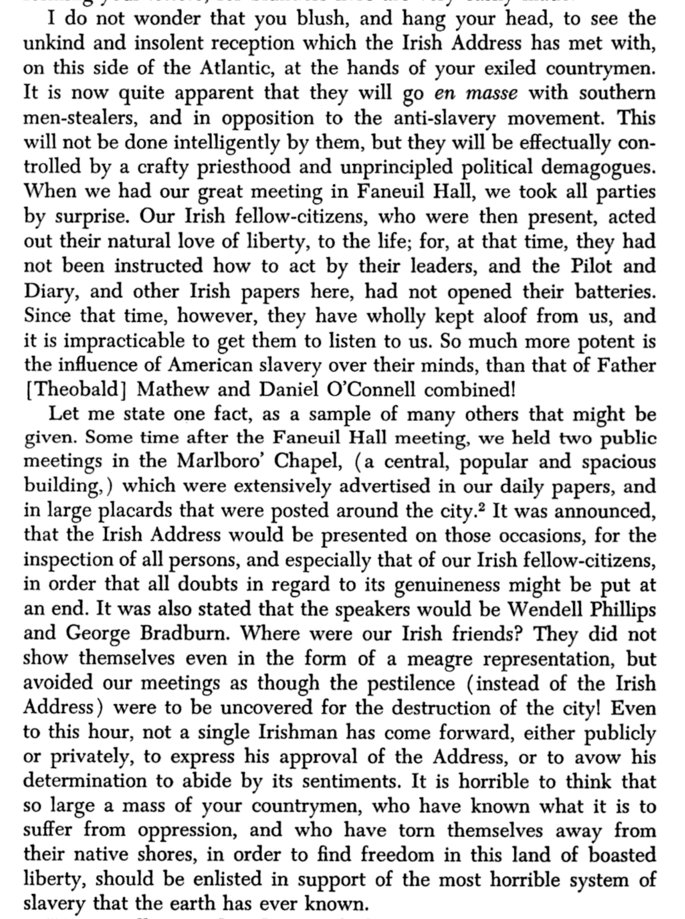

In 1868 The Irish Republic, a Fenian newspaper in Chicago, shunned the racist policies of the Democratic party which had almost total Irish support (and voted as a bloc against black suffrage) to endorse the Fifteenth Amendment. "Liberty, to be just, must be universal."

Correction: This newspaper was established by members of the Fenian Brotherhood in Chicago in 1867 before moving to New York in the Spring of 1868.

Irish Nationalists in the U.S. were overwhelming hostile to abolitionism and racial equality, but there were exceptions. Another was Patrick Ford, a Famine emigrant from Co. Galway who worked for William Lloyd Garrison when he was just fifteen.

According to David Brundage, after serving in the Union army Ford "took over editorship of the South Carolina Leader, a Republican newspaper that fought for African American rights in the Reconstruction South." He moved to New York in 1870 & established the Irish World newspaper.

Brundage: "Ford used the Irish World to fight against the powerful currents of racism within the labor movement, the Land League, and Irish America as a whole...he [also] asserted a fundamental Irish and Irish American identity with colonized peoples around the globe."

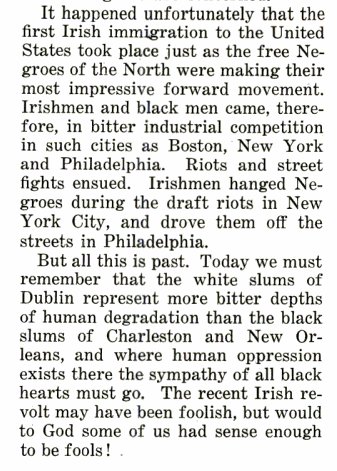

W.E.B. Du Bois: "The Irish people in the United States have often led in attacking blacks...this does not make less our desire for Irish freedom...It is the Oppressed who have been continually used to cow and kill the Oppressed in the interest of the Universal Oppressor." (1921)

Eamon de Valera: "Ireland is now the last white nation that is deprived of its liberty." (1920)

Du Bois was referring to Irish participation in anti-black pogroms and massacres in Philadelphia (1834, 1842), New York (1863), Memphis (1866), &c.

Edward Abdy re: Boston Irish (1833): "nearly all of them, who have resided there any length of time are more bitter and severe against the blacks than the native whites themselves. It seems as if the disease were more virulent when taken by inoculation than in the natural way."

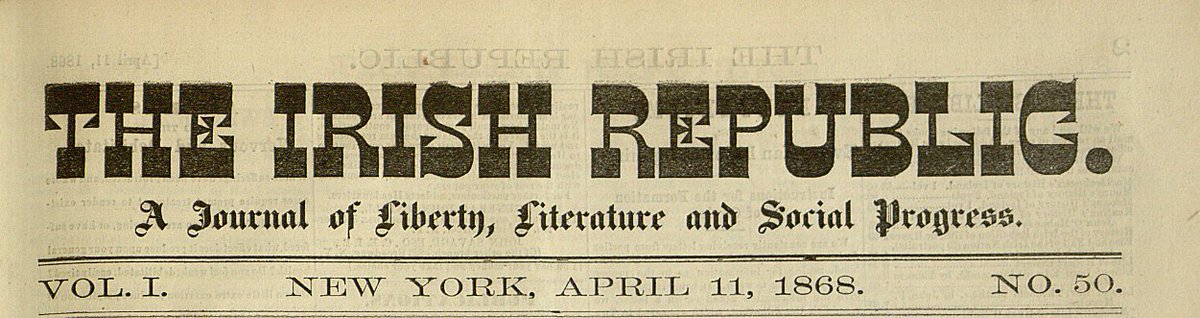

On 31st May 1866 George S. Boutwell spoke in favour of racial equality in Faneuil Hall in Boston. During this speech he chastised the members of the Irish American community who were pro-slavery before the war and who now opposed suffrage and civil rights for African Americans.

At this point the speech was interrupted when an unnamed gentleman in the crowd stated "I am an Irishman, and I am in favour of negro suffrage." Referring to the Civil War he said "I should like to ask if Irishmen have not fought bravely for the liberties of this country.."

Boutwell commended him and all Irishmen of similar views, declaring that they were not the target of his ire. He continued "so far as they fought under Sheridan and others, all honor to them; but it is not enough that the war be carried on upon the battlefield only."

"The contest of arms is over; but we approach a greater contest, in which the men already subdued in arms seek to enter the citadel of the republic, and seize the power of the nation for the perversion of the institutions of the country and the overthrow of liberty."

"I complain, not that Irishmen did not go into war and do duty on the battlefield, but that they now hesitate and allow themselves to be made the instruments of the ancient allies of traitors for the overthrow of the liberties of the people."

As anyone familiar with the history of the Reconstruction period in the U.S. will attest, Boutwell& #39;s warnings were far from exaggerated. It ended with the violent overthrow of what Du Bois termed "abolition-democracy" in the South.

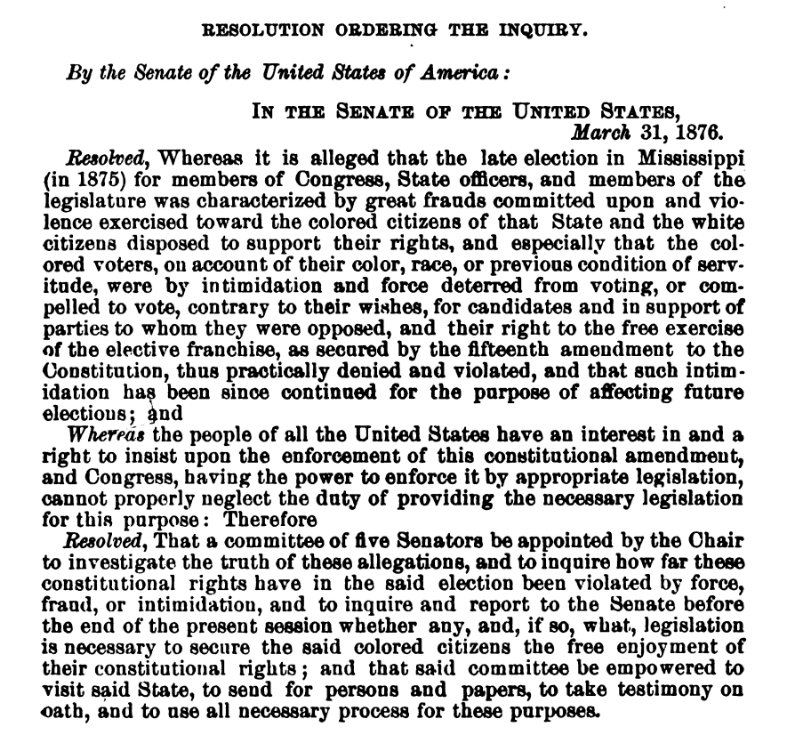

In 1876 Boutwell was appointed Chairman of the Mississippi Committee charged with investigating the elections of 1875 where white paramilitaries (e.g. Red Shirts) loyal to Democrats and ex-Confederates terrorised black voters & non-democrats to ensure white supremacist rule.

Map of Lynchings in the United States (1900-1931) https://www.loc.gov/item/2006636636/">https://www.loc.gov/item/2006...

Daniel O& #39;Connell: "Liberty in America means the power to flog slaves, and to work them for nothing." (1833)

Frederick Douglass (1849): “I am far from finding fault with the Irish for coming to this country [but] I met with an Irishman a few weeks ago [who] conversed with me on the subject of slavery and that man, newly imported to this country, gravely told me...”

”...that the colored people in this country could never rise here, and ought to go back to Africa. What I have to say to Ireland is, send no more such children here."

Enslaved Africans were present/being sold in Ireland at least as early as 1591 (in this case a slave ship had been intercepted by Irish mariners) and there are a number of adverts for the sale of slaves in Irish newspapers in the eighteenth century.

"A Neat beautiful black negro girl, just brought from Carolina, aged 11 or 12 years, speaks good English; to be disposed of." (Dublin, 1768)

“To be sold for account of D.F. a Black Negro Boy aged about 14 yrs, remarkably free from vice, a very handy willing servant" (Cork, 1762)

“To be sold for account of D.F. a Black Negro Boy aged about 14 yrs, remarkably free from vice, a very handy willing servant" (Cork, 1762)

Due to the imposition of navigation laws Irish merchants were precluded from directly engaging in the transatlantic slave trade (in Ireland) but many were very successful slave traders in the American colonies and in English and French ports (Liverpool, Bristol, Nantes &c)

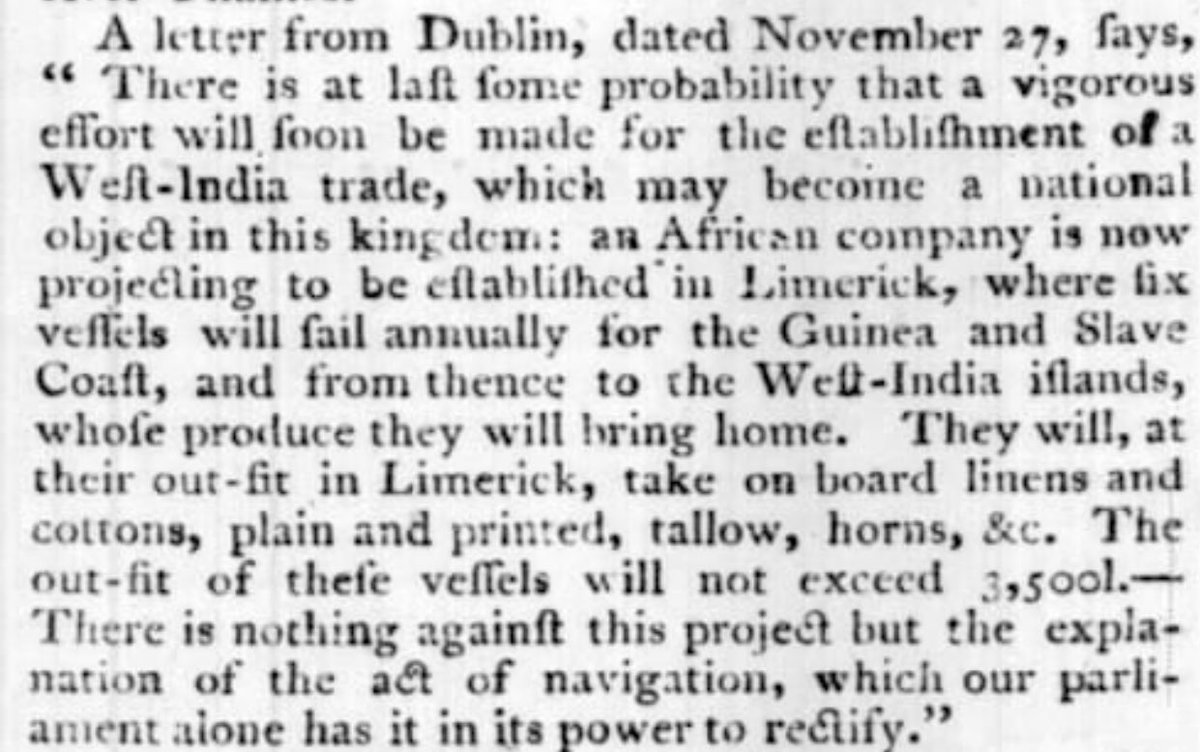

Thus slave trading directly from Ireland was extremely rare, but some voyages made it through. In 1718 the slave trading vessel "Prosperity" commanded by a Capt. Hourigan left Limerick for the Gold Coast (Ghana). At Cape Coast Castle the crew purchased 111 enslaved people.

The Middle Passage took 66 days and at least 15 slaves died. The survivors were sold into perpetual slavery to planters in Barbados and in Cuba.

In 1784 merchants in Limerick attempted to establish a slave trading company.

In 1784 merchants in Limerick attempted to establish a slave trading company.

Shall I..

David Tuohy from Tralee, Co. Kerry settled in Liverpool in the 1750s and captained at least four slave trading voyages (1766-& #39;71). In 1766 he sailed Sam, a Boston built vessel, from Liverpool to West Central Africa and bought 284 slaves. There were 32 Middle Passage deaths.

The survivors were sold in Barbados and Grenada. In 1767 he sailed aboard the Sally and sold the 234 survivors to planters in Antigua. On the same ship in 1769 he sailed to the Windward Coast, purchasing 200 slaves, and then sailed to the Gold Coast and purchased 130 more.

On this voyage 87 of his victims died during the Middle Passage, a 26.4% death rate. He sold the 243 survivors at Grenada. In 1771 he sailed the Ranger to West Africa and bought 257 slaves. 47 died during the Middle Passage. He sold the survivors at Barbados and at Antigua.

He had now made enough profit from his slave trading to become a slave ship owner. He was the part-owner of ten Liverpool slave ships from 1772 to 1786. Approx 1,500,000 Africans were transported to the Americas and sold into hereditary slavery via Liverpool slavers.

The second most "successful" French merchant in the transatlantic slave trade was Antoine Walsh, a French-Irish Jacobite based in Nantes. It is estimated that he purchased and enslaved c. 12,000 Africans to sell to planters in the French slavocracies, Martinique & Saint-Domingue.

He was a son of an Irish Jacobite exile in France, Philip Walsh of Co. Kilkenny. Antoine covered the costs and personally escorted Charles Edward Stuart to Scotland in his ship during the Jacobite Uprising of 1745. This Walsh family was admitted into the French noblesse in 1751.

The French historian M. Gaston Martin remarks that "they had by then sold a sufficient number of negroes to enable them to regild and legalise their Irish coat-of-arms which was a little sullied by the somewhat dubious trade [in which] the Walsh dynasty was engaged."

The Walsh’s invested some of their slave trade earnings into colonial plantations and purchasing the Château de Serrant. The first slave ship that Antoine Walsh captained was the Saint Jean Baptiste, which left Nantes in June 1728. It arrived at the coast of West Africa in August

For six weeks Walsh collected his ‘cargo’ and set sail for the Americas in October with 325 African people in chains. He arrived at French Guiana in November. By then 65 of his victims had died, their bodies presumably thrown overboard. He then sold the remaining 260.

He became increasingly wealthy as a slave trader and twenty years later established the Société d’Angole, which according to historian Nini Rodgers was “the first private joint-stock company in France devoted to the slave trade.”

Around this time one of his ships were purchasing slaves off the coast of Whydah. This took over five weeks and "as the ship got ready to sail, six women, one with a child at the breast, threw themselves overboard and drowned." http://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/the-irish-and-the-atlantic-slave-trade/">https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th...

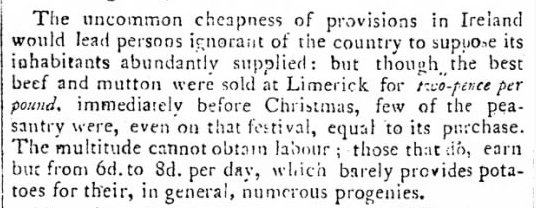

So while a number of Irish merchant families based at imperial hubs made fortunes from slave trading, most of the direct profiteering in Ireland from racial slavery was due to the export of cheap provisions to the European slavocracies and the import and sale of slave produce.

Provisions such as butter, beef, herring and pork were salted and exported via ports at Cork, Galway, Waterford, Dublin and Limerick. One cut of beef exported out of Cork was known as "Planters Beef" (1801). Shoes for enslaved people in the colonies were manufactured in Belfast.

Slave produce such as sugar and tobacco was then imported into Ireland, taxed, and then sold by grocers across Ireland e.g. an advert for Jamaica sugar on sale in Limerick in 1815.

How were these provisions so cheap? It& #39;s complex & requires further research but I posit that one factor is that the level of poverty in Ireland = a lack of work & depressed wages for labourers to the extent that few could even afford that which was exported *or* imported (1797)

Cf. after gainfully agitating for Free Trade this is how Irish merchants and landowners depicted their role on the world stage (1780) Kneeling before Hibernia are a Native American and an enslaved African. It& #39;s also the cover of Rodgers& #39; seminal work > https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9780333770993">https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9...

I& #39;m not going to explore Irish slave ownership in Colonial America and the U.S. in this thread, but you can read my essay and research about this here. Many Irish, no different than any other colonist, capitalised on this lucrative and barbaric opportunity https://medium.com/@Limerick1914/kiss-me-my-slave-owners-were-irish-86316555796c">https://medium.com/@Limerick...

Before I progress further, here are some threads which may also be of interest

1. https://twitter.com/Limerick1914/status/943661193587195904">https://twitter.com/Limerick1...

2. https://twitter.com/Limerick1914/status/709530568753602561

3.https://twitter.com/Limerick1... href=" https://twitter.com/Limerick1914/status/697366115601797120">https://twitter.com/Limerick1...

1. https://twitter.com/Limerick1914/status/943661193587195904">https://twitter.com/Limerick1...

2. https://twitter.com/Limerick1914/status/709530568753602561

3.

Next I want to discuss and expand on my previous thoughts on the overly simplistic yet immensely popular "how the Irish became white" narrative. It& #39;s a historically and geographically myopic concept and as such does not hold water.

The reality is that we were always legally designated as being ‘white’ from the moment the racial category was first deployed by colonists in the seventeenth century.

“White” was used to collectively identify colonists in the Americas who were from Western Europe. It served as a racial and imperial identifier, by definition oppositional, to separate them from Africans they enslaved and the indigenous peoples they colonised and dispossessed.

Ignatiev& #39;s thesis ignores Irish participation in colonial conquest and racial slavery in the Americas from the 1600s to the 1800s, omits Irish migration to the Antebellum South and fails to explore if these ideologies and/or associated prejudices were present back in Ireland.

It& #39;s also crucially important to understand that the Atlantic ocean was not something that separated or divided, but was a mainline connection, and that the racist concepts, ideologies and terminology used to justify colonisation/enslavement flowed in both directions.

Thus in the mid-19th century U.S. it was less a case of first generation Irish immigrants “becoming” white and more that they could, if they wished, assert their white identity with violent impunity for their own benefit, in a white supremacist nation.

This racial identity was implicit and not conditional on their behaviour or politics. Whether Irish migrants were anti-slavery or pro-slavery, racist or anti-racist, they were white.

I *highly* recommend Eric Foner& #39;s review of Nell Irvin Painter& #39;s "The History of White People" as it& #39;s a succinct history lesson. http://www.ericfoner.com/reviews/092010harpers.html">https://www.ericfoner.com/reviews/0...

"No one had tried to prevent Irish immigrants from voting on the grounds that they were not white, hauled them into court for marrying white persons, or claimed that the law prevented them from becoming naturalized citizens."

"The elevation of whiteness to an all-purpose explanation for political, social, and cultural behavior ignored the fact that the “white” category contains within itself many kinds of inequality."

U.S. Statute (1790): "To establish an uniform rule of naturalisation [for] any alien, being a free white person."

Supreme Court (1857): African Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not and could never be citizens of the United States.

Supreme Court (1857): African Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not and could never be citizens of the United States.

W.E.B. Du Bois (The Souls of Black Folk, 1903): "Instead of standing as a great example of the success of democracy and the possibility of human brotherhood America has taken her place as an awful example of its [failures], so far as black and brown and yellow ppl are concerned."

"This, too, in spite of the fact that there has been no actual failure; the Indian is not dying out, the Japanese and Chinese have not menaced the land, & the experiment of Negro suffrage has resulted in the uplift of 12 million people at a rate probably unparalleled in history."

"But what of this? America, Land of Democracy, wanted to believe in the failure of democracy so far as darker peoples were concerned. Absolutely without excuse she established a caste system, rushed into preparation for war, and conquered tropical colonies."

"She stands shoulder to shoulder with Europe in Europe& #39;s worst sin against civilization. She aspires to sit among the great nations who arbitrate the fate of "lesser breeds without the law" and she is at times heartily ashamed even of the large number of "new" white people..."

"...whom her democracy has admitted to place and power. Against this surging forward of Irish and German, of Russian Jew, Slav and "dago" her social bars have not availed, but against Negroes she can and does take her unflinching and immovable stand."

"She trains her immigrants to this despising of "niggers" from the day of their landing, and they carry and send the news back to the submerged classes in the fatherlands."

Fenian leader Tom Clarke (West 36th Street, New York, 1900): "[It& #39;s] a rather bad neighbourhood. There are any amount of niggers living here about and we Irish as a rule don& #39;t care for coming too much in contact with the coloured folks."

His wife Kathleen Clarke replied from Limerick: "I suppose those niggers were too much for you. I must say I& #39;ve an objection to them myself."

Tom Clarke, a signatory of the 1916 Proclamation and a leader of the Easter Rising, was executed by the British on 3 May 1916.

Tom Clarke, a signatory of the 1916 Proclamation and a leader of the Easter Rising, was executed by the British on 3 May 1916.

In the wake of the revolutionary uprising in Dublin, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote an editorial for the @thecrisismag wherein he once again put aside Irish anti-blackness and expressed his concern for the immense poverty in Dublin and sympathy for the 1916 Rising itself.

To return to Kathleen Clarke& #39;s response from Ireland, it challenges assumptions in the "became white" thesis and highlights the issue of anti-black prejudice in Ireland both before and after the crisis migration that occurred during the Great Famine.

When the Irish abolitionist Richard D. Webb accompanied the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond on his lecture tour of Ireland in 1841 he noted that while Remond suffered no racist abuse or discrimination, this did not mean that these attitudes were absent.

“Remond has, hitherto, had no battle to meet in Ireland - neither unkindness, nor persecution...Prejudice and ignorance have barred his way in England. The same elements exist in Ireland, but they have not been suffered to come in his way.“

Another important factor re: attitudes that migrants may have carried to the U.S. was mentioned by Webb during this tour. He felt that many in Ireland struggled to understand chattel slavery and that this gap in knowledge undermined efforts to garner sympathy for the cause.

Remond was even asked “what are you going to do for the white slave?” during a lecture. Webb explained that Irish people were "so used to abject want and enormous luxury, that slavery is not readily looked on so much in the robbery of rights, as a privation of advantages."

“The wickedness of man’s holding property in man is forgotten in the description of the supply of food, the imposition of labour, the quantity of clothing, and the animal wants of the man."

"Slavery being unknown amongst us, we are tempted to confound it in our minds with the lowest position of humanity with which we are familiar. This is perfectly natural, but extremely fallacious.”

It was difficult for abolitionists to make progress when a distorted perception of American slavery and a widespread distribution of stereotypes about African Americans (free or enslaved) were consumed as a form of entertainment in 19th century Ireland, i.e. minstrelsy.

Blackface shows were extremely popular in Ireland, while some of the leading blackface performers in the U.S. at this time were of Irish extraction. James H. Dorman posited that these minstrel shows provided “symbolic justification for keeping the Negro in his place”

Russell Nye highlighted the enduring power of their propagandic effect as abolitionists had to “spend thirty years convincing the public that life under slavery was not like a minstrel show”.

Robert C. Toll concluded that minstrelsy “unequivocally branded Negroes as inferiors” and that the common minstrel themes of idyllic slavery in Southern plantations contrasted with urban strife was “an ideal device for asserting that Negroes had no place in the North.”

In & #39;Blacks and Blackface on the Irish Stage, 1830-1860& #39; Douglas Riach is critical of Irish abolitionists for not doing more to condemn the minstrel shows in Ireland and argued that those who immigrated possibly carried these racial prejudices/misconceptions about slavery w/ them.

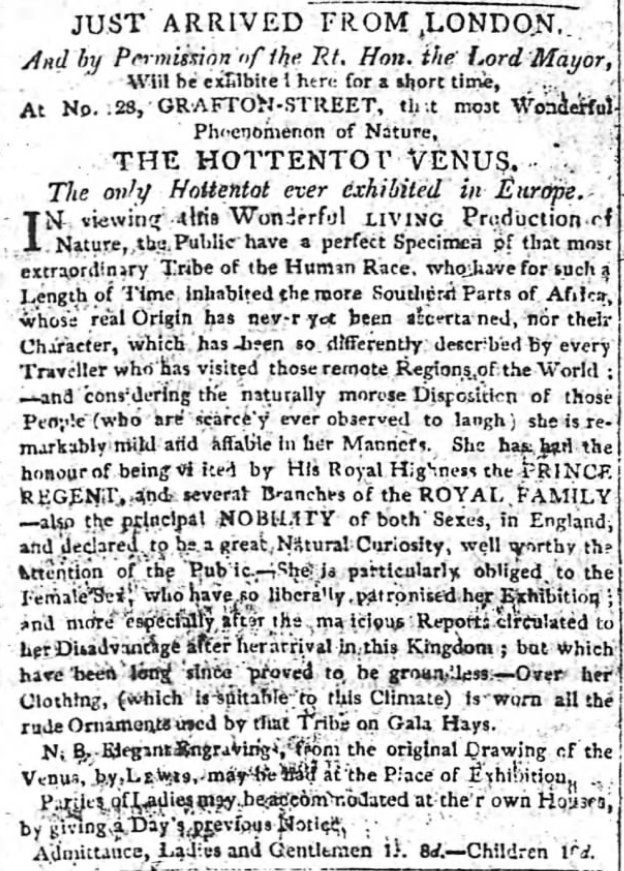

During the 19th century African people were literally put on display in Ireland as objects of curiosity. In Dublin Saartjie Baartman and a human zoo of "Bosjesmans" were "exhibited" to the public in 1812 and 1848 respectively.

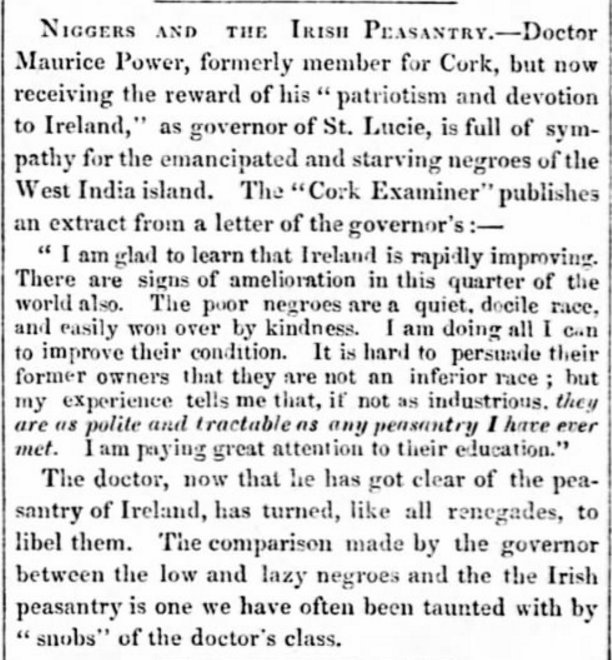

Like today, white supremacy could be adopted by people in Ireland who never spent time in the U.S., e.g. see the racism of the editor of the Waterford News (1853) when he rejected a comparison between the impoverished Irish & the former slaves in the West Indies as being "libel"

(There is also racism in Dr. Power& #39;s comments but this thread is long enough as it is!)

Many of our ancestors used black people as their slaves in the colonies while some of our leaders have historically used the reality of racial slavery to embellish their arguments or rhetoric. The enchattlement of millions of people reduced to a mere figurative usefulness.

People of my parent& #39;s generation still use phrases like "I was working like a black" or "we were working like n*****rs". Usually meaning being overworked for little or no pay or acknowledgment. Forgotten about. Exploited.

This tells us that slavery, blackness and social invisibility are unconsciously associated in their minds even though they may know little of the history of Ireland in the Black Atlantic. This speaks volumes as this history remains relatively absent in our education system.

From the 1919 to 2014 the racial slur "n****r" was used by elected representatives in Dáil Éireann and the Seanad over 150 times. Only a handful of these were recent examples where deputies were discussing and highlighting anti-black racism.

The most common usage was when deputies used the racist idiom “n****r in a woodpile” (a 19th century U.S. phrase which links criminality to race) or the racist novel “ten little n****rs”. Of course both of these phrases have their origins in the world of minstrelsy and blackface.

There is very little evidence of any pushback when the slur was used. One exceptional occasion occurred on the 15 Dec 1966 when Brendan Corish (Labour) challenged Martin Corry& #39;s (Fianna Fail) use of the term. Twice he asked Corry to clarify "what is a n****r"? but to no avail.

He then addressed an Leas-Cheann Comhairle (Cormac Breslin, Fianna Fáil): "I do not think he should be allowed to describe people who are not of the same colour as people in this country as "n****rs."

An Leas-Cheann Comhairle replied: "N****rs" is not a disorderly word."

An Leas-Cheann Comhairle replied: "N****rs" is not a disorderly word."

Corish: "It may not be, within the traditions of the House, but I think it is an objectionable word."

Sin é. End of thread.

Sin é. End of thread.

I& #39;ll leave the final word to Du Bois: "above the shackled anger that beats the bars, above the hurt that crazes there surges in me a vast pity -- pity for a people imprisoned and enthralled, hampered and made miserable for such a cause, for such a phantasy!"

Du Bois on the white supremacist backlash to Reconstruction: "Unfortunately there was one thing that the white South feared more than Negro dishonesty, ignorance, and incompetency and that was Negro honesty, knowledge, and efficiency.” (1915)

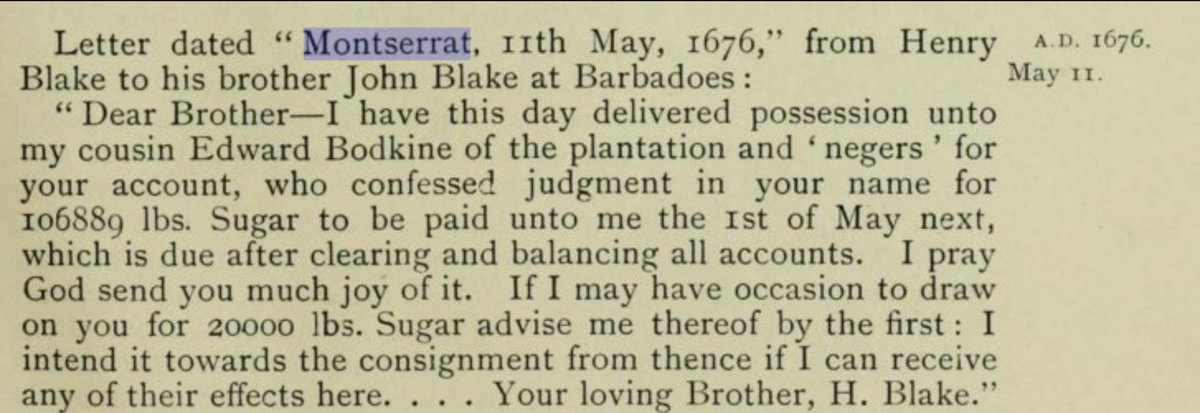

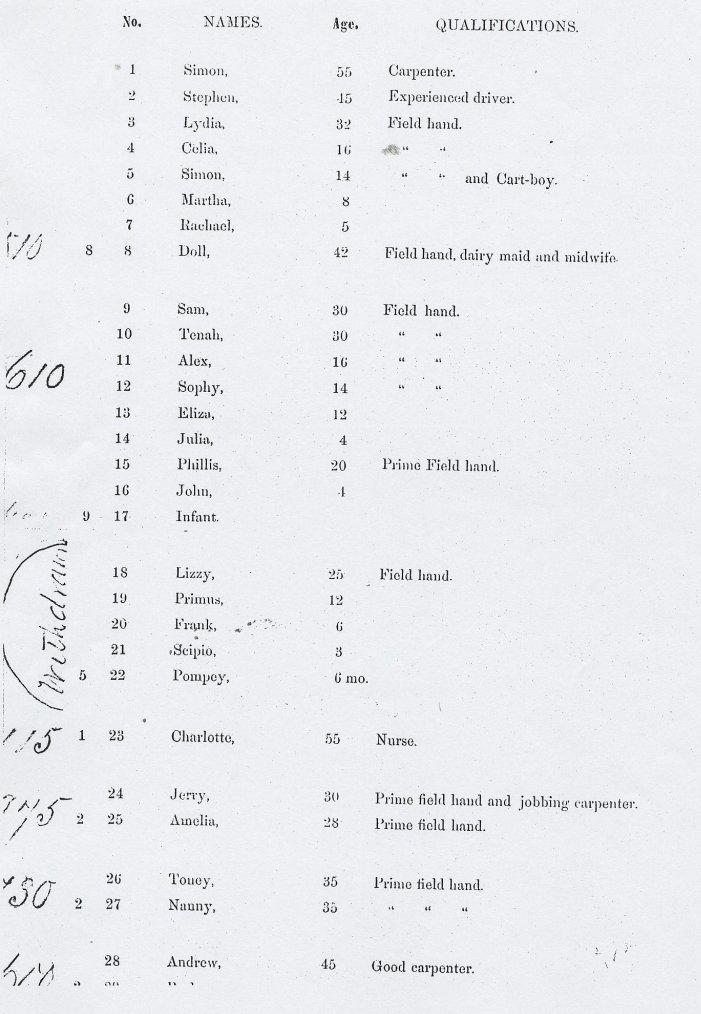

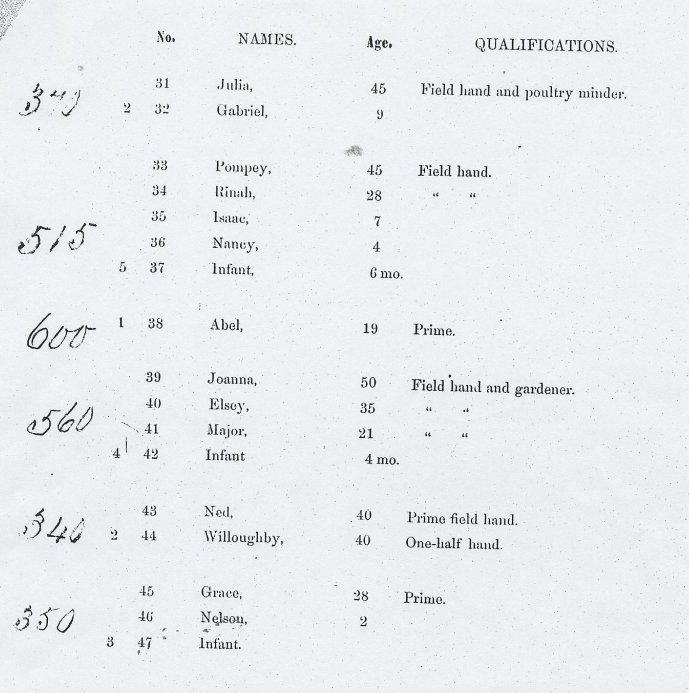

In 1655 John Blake& #39;s family in Galway had most of their land confiscated by Cromwell and were transplanted to a smaller estate in Mullaghmore. In 1668 three of his sons migrated to the Anglo-Caribbean. They aimed to make enough money to reestablish their dynasty back in Ireland.

They bought plantations in Montserrat and were established as traders in Barbados. In 1676 Henry Blake cashed out. He owned 36 enslaved Africans at this time. He returned to Ireland and bought two estates with his profits. Lehinch, Co. Mayo and Renvyle, Co. Galway.

These estates remained in family ownership into the 1800s. http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie:8080/LandedEstates/jsp/estate-show.jsp?id=520"> http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie:8080/LandedEstates/jsp/estate-show.jsp?id=520 Back in Barbados John Blake was a slave owner and trader who did not do as well. So he moved to Montserrat and purchased his brother& #39;s plantation (along with his cousin Edward Bodkin)

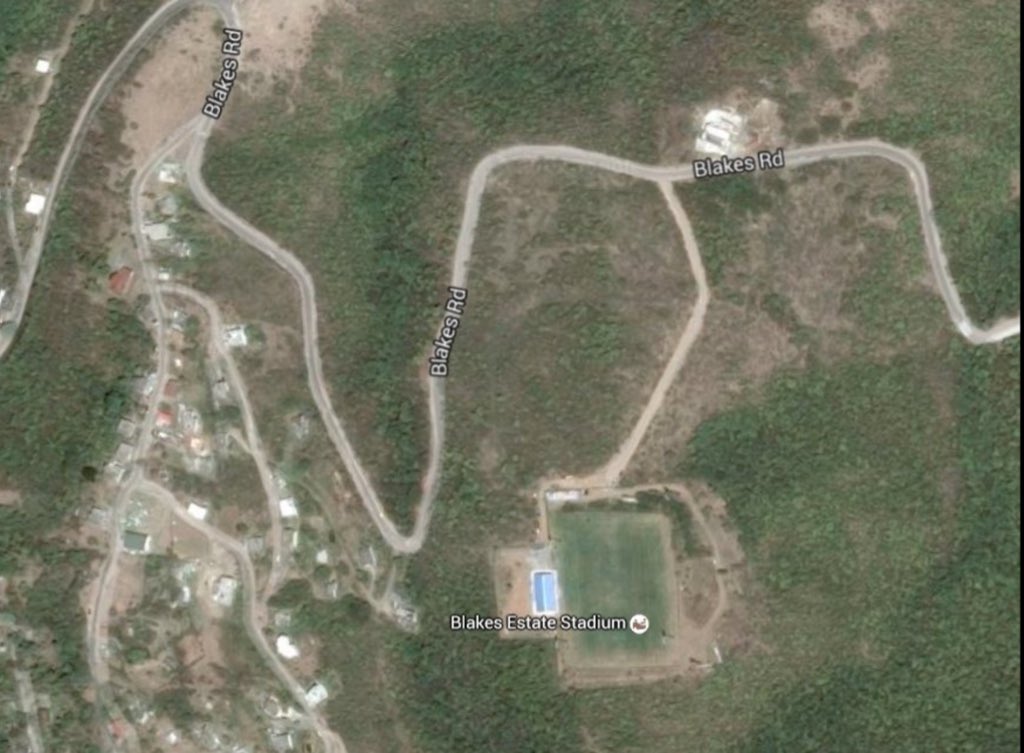

This sugar plantation became even more profitable (via the forced labour of their slaves) and to this day this part of Montserrat remains named after these Irish planters and enslavers.

John Blake died in 1692 and his land and enslaved workforce passed to his daughter Catherine. She married Nicholas Lynch, an Irishman who owned plantations in Antigua and St. Christopher.

By the 1740s the Blake & Lynch firm had "became one of the great London commission houses in the sugar trade" https://books.google.com/books/about/Irish_Immigrants_in_the_Land_of_Canaan.html?id=Kl7tsbpslc4C">https://books.google.com/books/abo...

And in 1766 we find an advert for a large scale slave auction in Barbados: "270 Whidah and Popo Slaves...sale will begin at 10 o& #39;clock."

Organising this sale was an Irish firm, Anthony and Dominick Lynch of Bridgetown, Barbados. (See ‘Irish-American Trade, 1660-1783’ by Truxes)

Organising this sale was an Irish firm, Anthony and Dominick Lynch of Bridgetown, Barbados. (See ‘Irish-American Trade, 1660-1783’ by Truxes)

The Rice family from Limerick were another Irish Catholic dynasty that made a fortune from sugar planting/slave-owning in 17th century Barbados. Jenny Shaw& #39;s ‘Everyday Life in the Early English Caribbean& #39; traces the Barbadian life of Nicholas Rice and his nephew George.

Nicholas was a wealthy merchant and George was a successful planter. In his will Nicholas left £120 to "the Roman Catholique Clergy of the Citty of Lymericke where I was borne." (1677)

George, who owned a large plantation comprising 301 acres, including many slaves, bequeathed £50 in his will to the poor of Limerick. (1684) He also left £14 to the "poor Irish people" in the parish of St. Philip, Barbados.

Nicholas also left 50k lbs of sugar to his “poor Irish” neighbours. This Rice family were elites and it bears repeating that the majority of Irish Catholics in 17th C Anglo-Caribbean were indentured servants (many of whom were forcibly sent there in the 1650s) or free labourers.

Report to Barbados Council (1655): "...severall Irish servants and negroes [slaves] out in rebellion in ye Thicketts..." In response to this they raised a regiment to "follow the said servants and runaway Negroes" and "suppress or destroy them."

Planters in Barbados were paranoid about Irish servants and freemen allying themselves with enslaved Africans, but this rarely happened. The evidence points to occasional incidents of collaboration for mutual benefit (like marronage) and not common revolt on any scale.

Hilary Beckles concluded that "Fear outran fact in this regard: no certain evidence exists that servants or freemen ever attempted to participate in [a] violent uprising of slaves. The reality was that the poor whites benefited, though marginally, from black slavery.."

In 1686 22 enslaved Africans and 18 Irish servants were arrested on suspicion of plotting a slave revolt. All of the enslaved were executed and all of the Irish servants were freed.

In 1692 another conspiracy to revolt was apparently discovered. A small number of Irish (it& #39;s unclear if they were free or indentured) were arrested and released while 92 enslaved Africans were executed by the plantocracy, with four dying of wounds inflicted by castration.

The Catholic Irish in the 17th century Caribbean were much more likely to combine with their co-religionists, i.e. the French and the Spanish. There are a no. of examples of this in various colonies (Montserrat, St Kitts, &c) where they actively fought with the "invading" force.

It& #39;s also thought that St Kitts was used as a base by the French to organise and land a party of Irish on English Anguilla in 1688. In describing this event Oldmixon (British Empire in America, vol. II, 1708) underlines how the English classified and smeared the Irish people.

"..the Wild Irish, we call them so, to distinguish them from the English in Ireland [invaded] in the last war..."

Irish people (political prisoners, Tories and civilians) forcibly transported in the 1650s were also sold as servants in Bermuda, and the same mutual distrust and hostility between Irish servants and English authorities in Barbados was also present there.

In 1657 the court warned masters of Irish servants "to take care that they straggle not night nor daie, as is too common with them" and that in future no colonist in Bermuda was to "buy or purchase any more of the Irish nation whatsoever."

The same paranoia about Irish servants joining forces with enslaved Africans was also evident. In 1661 the governor of the colony announced that he had been informed of a "dangerous plott or combination by the Irish and Negroes."

He added: "If the said Irish cannot have their ffreedom their intentions are...to cutt the throats of our Englishmen." There are no records of any trials or arrests.

Tellingly the Governor& #39;s proclamation about this supposed plot included a reference to the 1641 massacre in Ireland. To understand these tensions in the Anglo-Caribbean it& #39;s important to be aware of the invasions, violence, antagonisms, psychologies and scars in the home nations.

To return to Barbados, a number of wealthy Catholic merchant families from Limerick that were based there in the early 1700s purchased plantations in South Carolina. Their surnames should be familiar to anyone that knows Limerick; Arthur, Roche and Mahon.

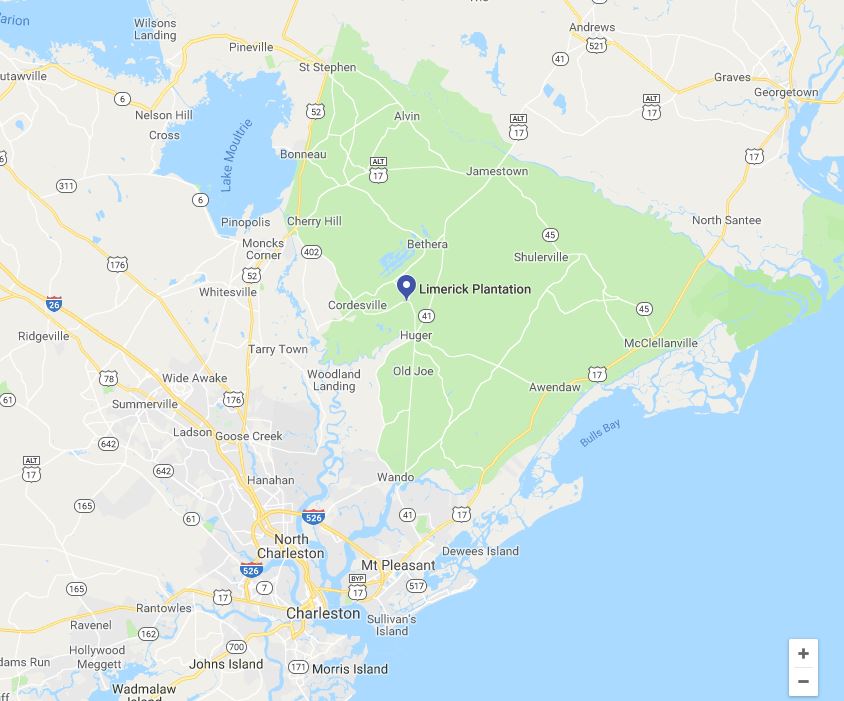

Almost six decades later a certain Francis Roche placed an advert for his runaway slave in the South Carolina Gazette. This enslaved person& #39;s name was "Limerick".

Present-day: The gates of Limerick Plantation, South Carolina.

Present-day: The gates of Limerick Plantation, South Carolina.

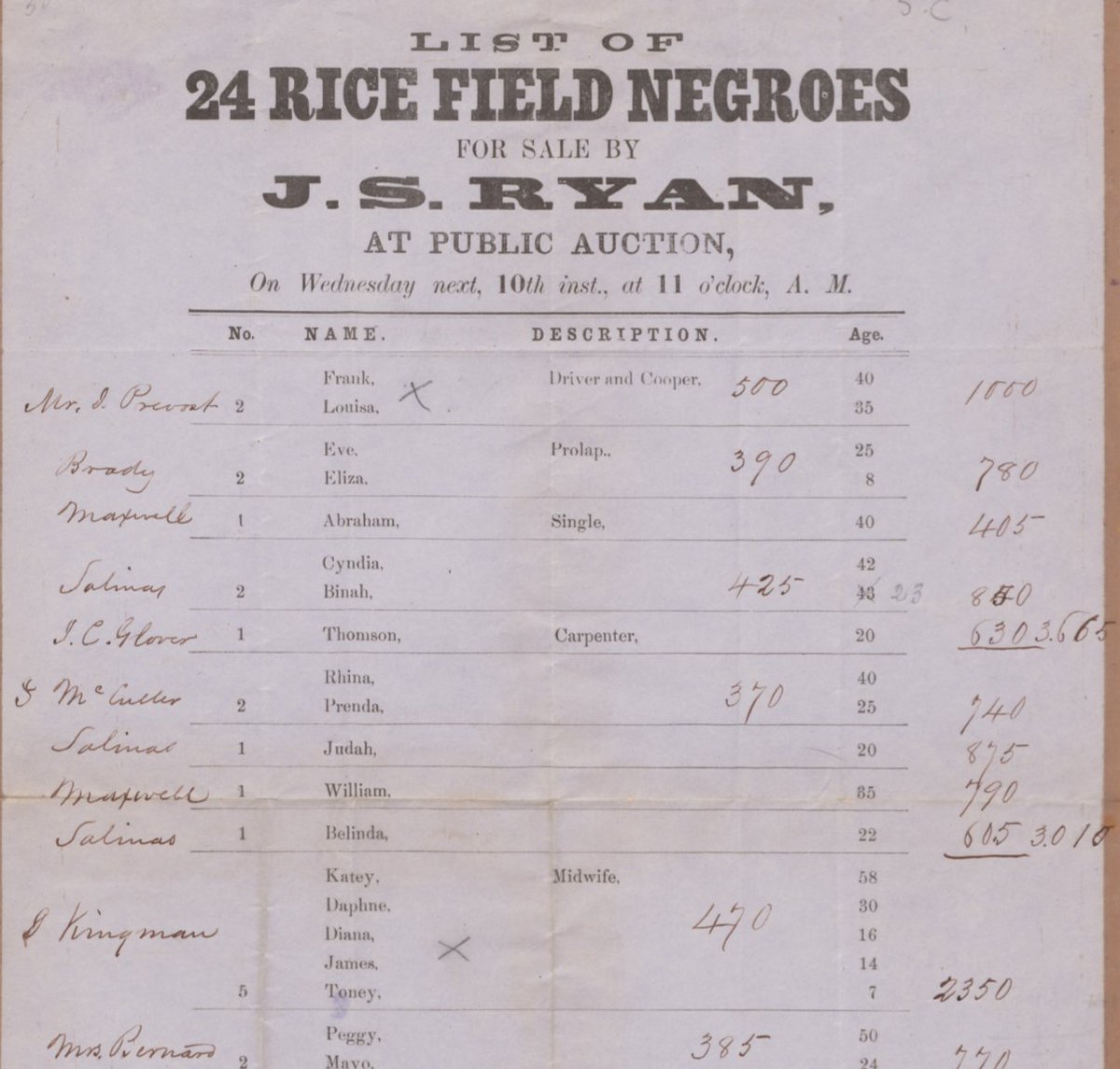

By the mid-19th century one of the most prominent slave traders in Charleston, South Carolina was Thomas Ryan, an Irish American. He opened a new slave mart in 1856. It was a complex of buildings which included a barracoon and a “dead house”.

As @dgleesonhistory recounts in "The Green and the Gray: The Irish in the Confederate States of America", the Irish-born Bishop of Charleston Patrick Lynch sold slaves “he owned personally and those bequeathed to him from pious Catholics” through Thomas Ryan.

When the Slaveholders& #39; Rebellion began in 1861 the Ryan slave traders joined the Confederate Army, helped recruit soldiers and raise companies. Thomas Ryan used his Irish heritage to encourage Irishmen to join the slaveholder& #39;s cause by invoking the memory of Oliver Cromwell.

"Oliver Cromwell lives again in the person of Abraham Lincoln. Should they succeed in capturing Charleston the butcheries of Drogheda will be repeated in our streets."

I know this has been an absurdly long thread (even by my standards) but I have one last extension to add tomorrow.

I’m going to post examples I have discovered over the past few years of Irish immigrants in the U.S. in the 19th and early 20th century who were black or mixed race. Some were gaeilgeoirí. How they were reported on highlights a ‘politics of purity’ used to police Irish identity.

First some context on why it should not be a surprise that a tiny minority of Irish immigrants in the U.S. in the nineteenth century were black. W.A. Hart has estimated that approximately 2,000 people of African descent were living in Ireland in the eighteenth century.

While many were enslaved in Ireland at this time (see newspaper adverts for sales and runaways) this was not the whole story. Others were servants and freed slaves. Some were professionals.

Hart& #39;s pioneering article "Africans in eighteenth-century Ireland" opens with an anecdote from Dublin (1777) where in St. Stephen& #39;s Green "a female black and child...was so closely pressed by the multitude of people crowding round, and staring at her..." that they had to rescued.

The newspaper report goes on to state that "Had she in any manner differed from others of her colour and country so common to meet with, it might have been some apology, to gratify curiosity; that not being the case, it reflects both scandal and ignorance on the company..."

Thirteen years later the United Irishman William Drennan noted that among James Napper Tandy& #39;s personal group in a march to the Dublin hustings in 1790 was "a young negro boy, well-dressed and holding on high the Cap of Liberty."

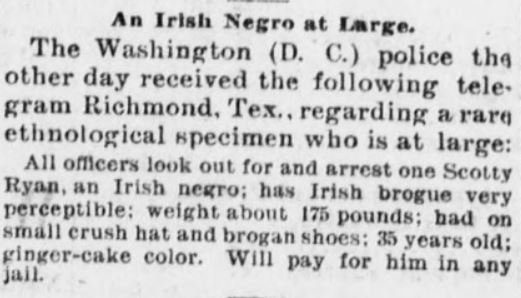

Scotty Ryan: an “Irish negro” with “Irish brogue very perceptible” - The Sea Coast Echo, 13 April 1895.

Peter Burke: "colored", "informed the police that he was an Irish n****r.” - The Sun (Delaware) 26 Sept 1901.

Peter Burke: "colored", "informed the police that he was an Irish n****r.” - The Sun (Delaware) 26 Sept 1901.

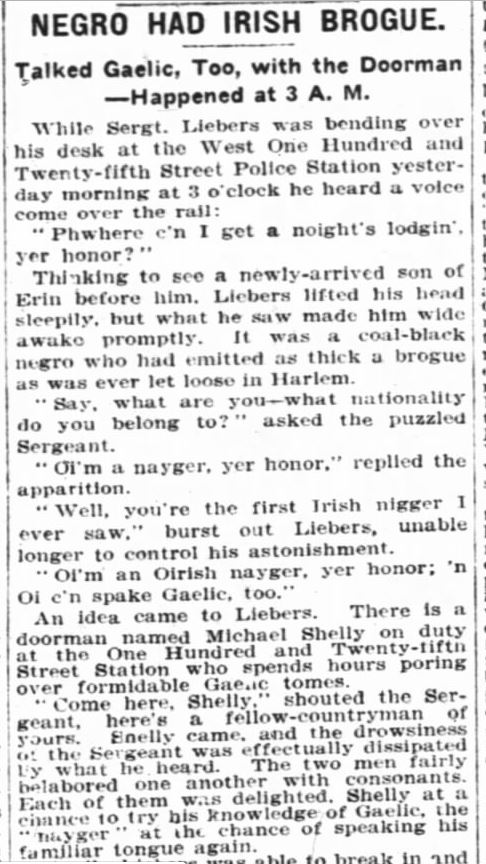

Unnamed Irish immigrant in New York. Born in England but moved to Ireland as a child. He was an Irish speaker who had recently arrived in the U.S. “Negro had Irish brogue. Talked Gaelic, too, with the Doorman” (New York Times, 30 Jan 1905)

Mike Hicks: “answered that he was as good as any “white Irishman” that ever lived in the Bay Area”. Probably second or third generation? (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 31 May 1888)

Tom Nolan: "probably the only Irish born negro in Pennsylvania..." (The Allentown Leader, 23 July 1903.

Unnamed Irish immigrant: "a negro...taken up in St. Louis, as a runaway or vagrant, turns out to be a free Irish emigrant, born in Waterford..." (The Daily Journal, 04 Sep 1854)

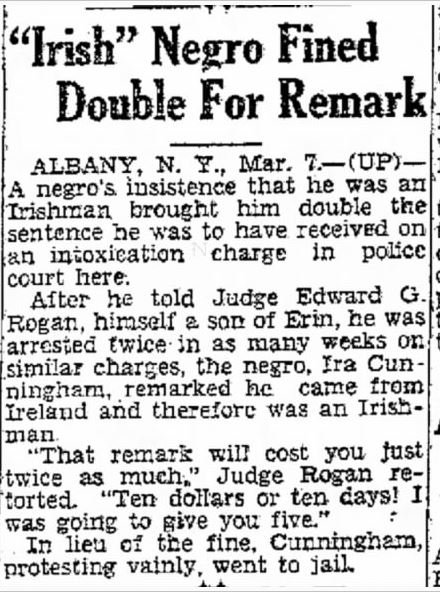

Ira Cunningham: fined double by Irish American judge for remarking that "he came from Ireland and was therefore an Irishman" (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, 07 Mar 1931)

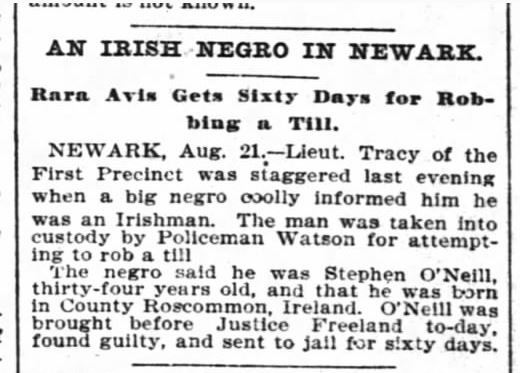

Stephen O& #39;Neill: Irish immigrant from Roscommon (The New York Times, 22 Aug 1897)

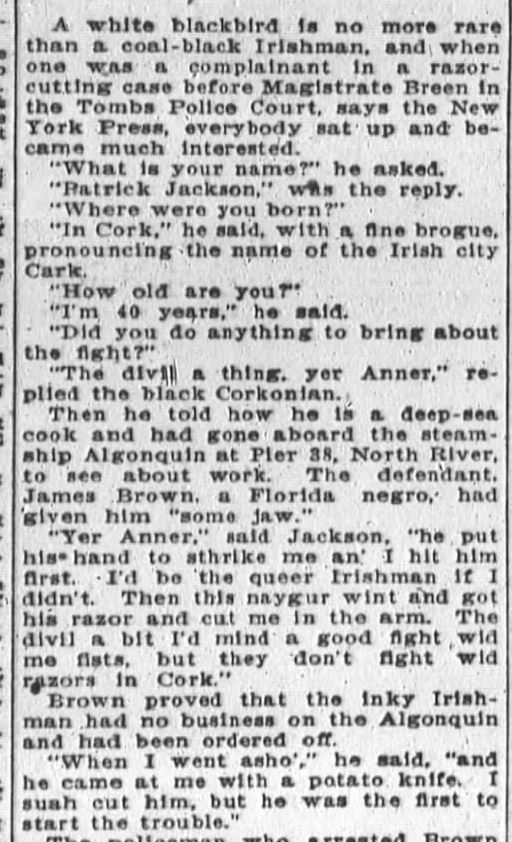

Patrick Jackson: Irish immigrant from Cork who spoke "Gaelic fluently and conversed in that tongue with an Irish policeman while waiting for the case to come up." (San Francisco Chronicle, 13 Oct 1906)

“Mulatto Jack” was an Irishman kidnapped & sold into perpetual slavery in Antigua. Sixteen years later he was imprisoned as a suspect during a slave conspiracy. What does his plight tell us about Ireland’s historical relationship with the Black Atlantic? https://medium.com/@Limerick1914/an-irish-slave-in-antigua-7acfb106a8e9">https://medium.com/@Limerick...

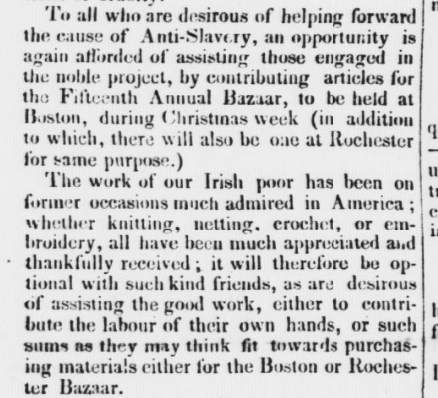

To return to the start of this thread, in October 1848 Frederick Douglass& #39; North Star newspaper paid tribute to the Cork Ladies& #39; Anti-Slavery Society who continued their abolitionist work in the midst of "famine, revolution and rebellion."

This society helped the fundraising efforts of the anti-slavery movement in the U.S. by sending handmade crafts that were sold at an Annual Bazaar. It seems middle or upper class members purchased the materials while the working class provided their time, labour and skill.

I now want to jump back to the late eighteenth century. Irishman James E. Murphy was a planter and slave trader based in St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies. In 1796 he purchased Water Lemon Estate in the neighbouring slavocracy of St. John and renamed it Leinster Bay Estate.

By the early 1800s he had become the largest sugar planter and slave-owner in the colony. At the time of his death in 1808 he had amassed 1,245 acres, of which 494 were planted with sugarcane, and his workforce encompassed 591 enslaved Africans.

Murphy was also a slave trader and sold at least eleven shipments of slaves from the Danish colony of St. Thomas to Havana, Cuba from 1803 to 1807.

Murphy& #39;s heirs continued to profit from enslaved people until the abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies in 1848. In 1818 at least 47 enslaved Africans fled the Leinster Bay Estate because of the excessive violence they were subjected to by their overseer, Peter Brady.

A late 18th century report of slave ownership in St. Croix reveals other Irish (or perhaps Montserrat Irish) planters and slave-owners. The Tuite family owned four plantations and 653 slaves (of which 200 were children).

T. O& #39;Neal: 1 plantation and 145 slaves (of which 35 were children)

J. Meade: 1 plantation and 85 slaves (34 children)

J.W. Delany: 1 plantation and 76 slaves

C. Nugent: 1 plantation and 112 slaves (18 children)

J. Meade: 1 plantation and 85 slaves (34 children)

J.W. Delany: 1 plantation and 76 slaves

C. Nugent: 1 plantation and 112 slaves (18 children)

In & #39;Slave Society in the Danish West Indies& #39; Hall notes that as well as plantation ownership the Irish in these colonies "proliferated as overseers and bookkeepers."

This can be also seen in British Guiana. Among the Demerara related correspondence of Dr. Hynes (an Irish Dominican missionary from Cork) is the story of a Cork man named Haynes, who was a migrant worker who arrived in the colony destitute after his time in the United States.

This Irish Dominican missionary helped Haynes out by getting him a job as an overseer of an enslaved workforce on a local plantation.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![U.S. Statute (1790): "To establish an uniform rule of naturalisation [for] any alien, being a free white person."Supreme Court (1857): African Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not and could never be citizens of the United States. U.S. Statute (1790): "To establish an uniform rule of naturalisation [for] any alien, being a free white person."Supreme Court (1857): African Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not and could never be citizens of the United States.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Drj1oSRW4AUWdwi.jpg)