In 1999, a great white dome rose in the heart of London, at the place where time begins.

What did it hold?

An artificial wonderland of dreams for a new millennium. A monumental public expenditure. A national boondoggle. "One amazing day".

The Millennium Dome - a design thread.

What did it hold?

An artificial wonderland of dreams for a new millennium. A monumental public expenditure. A national boondoggle. "One amazing day".

The Millennium Dome - a design thread.

In 1994, the Tory government established the Millennium Commission, with the purpose of funding new museums, exhibitions, and spaces to ring in the new millennium. The commission, which dissolved in 2006, would obtain its funds via payouts from the UK National Lottery.

Th Commission& #39;s primary purpose was to showcase "Britain& #39;s third millennium" on the world stage via an exposition.

Come 1997, Tony Blair& #39;s New Labour government - known for its "third way" political ideology - was tasked with its creation. (this will be important later).

Come 1997, Tony Blair& #39;s New Labour government - known for its "third way" political ideology - was tasked with its creation. (this will be important later).

Blair placed Peter Mandelson, then Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, as the public-facing chief of the dome project (this is also important). In actuality, the dome& #39;s construction and design was left to a private entity called the New Millennium Experience Company.

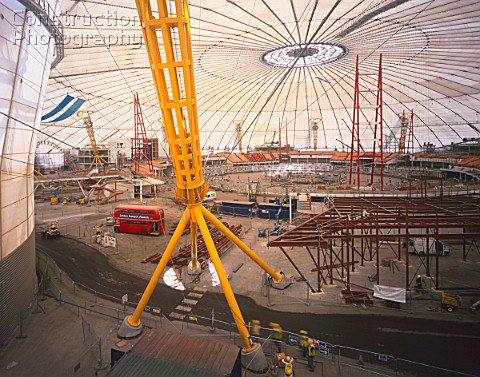

With an initial budget of £399 million GBP (£714 million), the Dome& #39;s construction began in 1998.

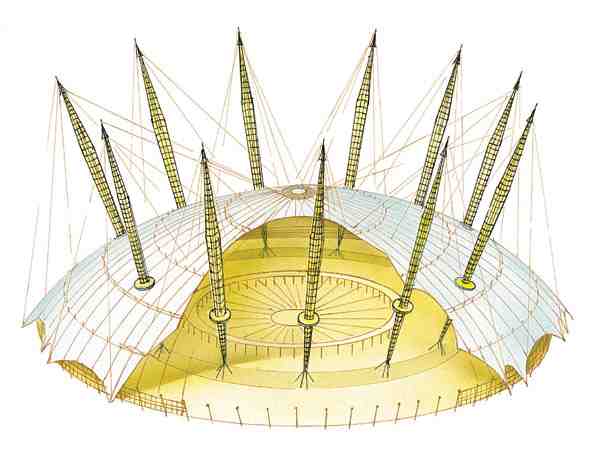

Before diving into its contents, let& #39;s talk about the dome itself - often overshadowed by its history, the structure is a modern marvel in its own right.

Before diving into its contents, let& #39;s talk about the dome itself - often overshadowed by its history, the structure is a modern marvel in its own right.

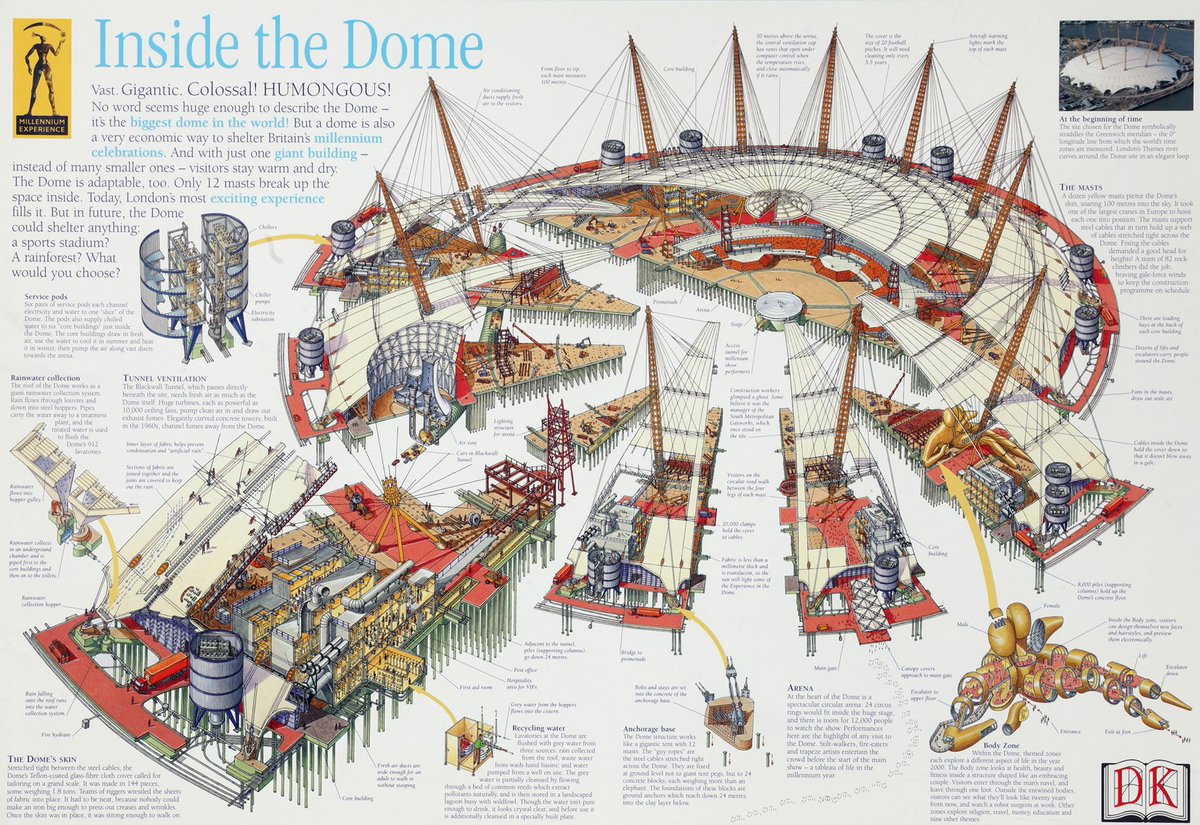

The dome itself - then the largest structure of its kind - is not a true "dome", but a freestanding tent, held up by 100m support towers. With no internal walls, the dome holds a massive 2.2 million cubic meters - built at an INCREDIBLY cost-effective £43m (£74m / $97m in 2018).

The dome& #39;s structure itself serves as a monument to time. Held up by its 12 supports, it reaches 52m high, and has a diameter of 365m - the months, weeks, and days of the year

Most importantly, it stands directly over the Greenwich Meridian Line - the place where GMT time begins

Most importantly, it stands directly over the Greenwich Meridian Line - the place where GMT time begins

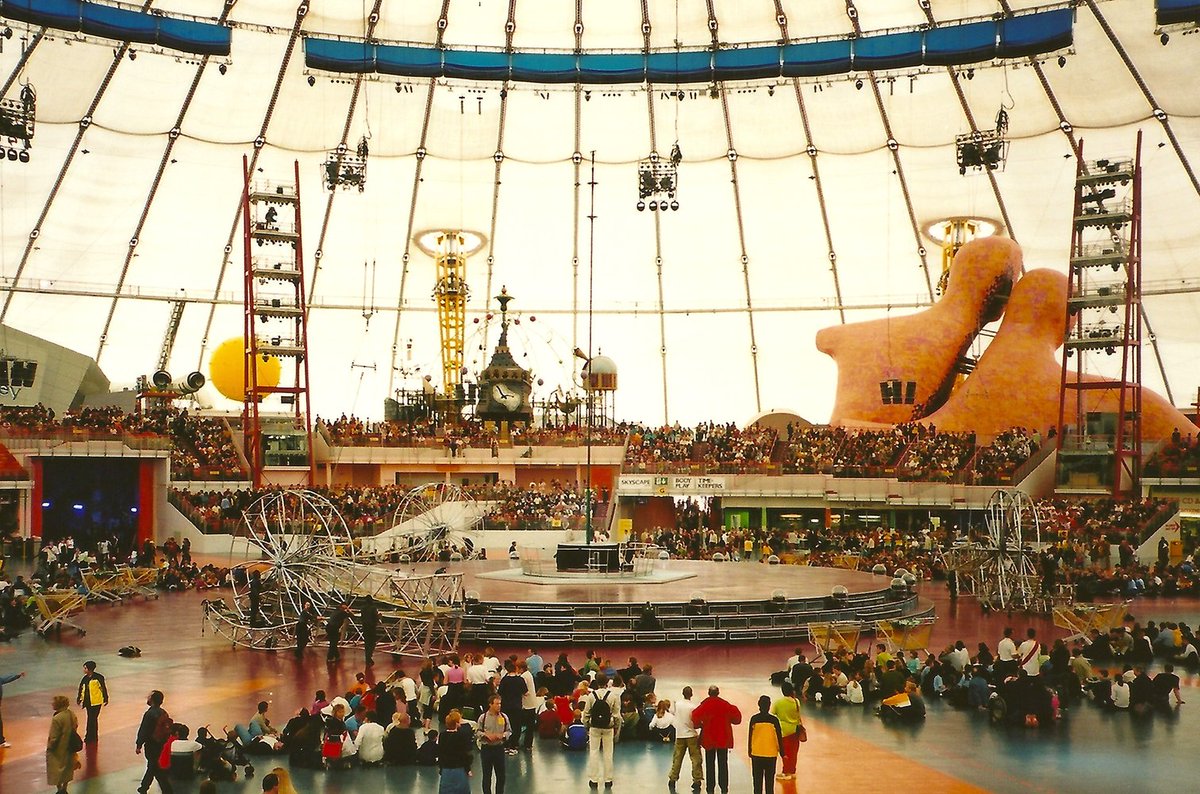

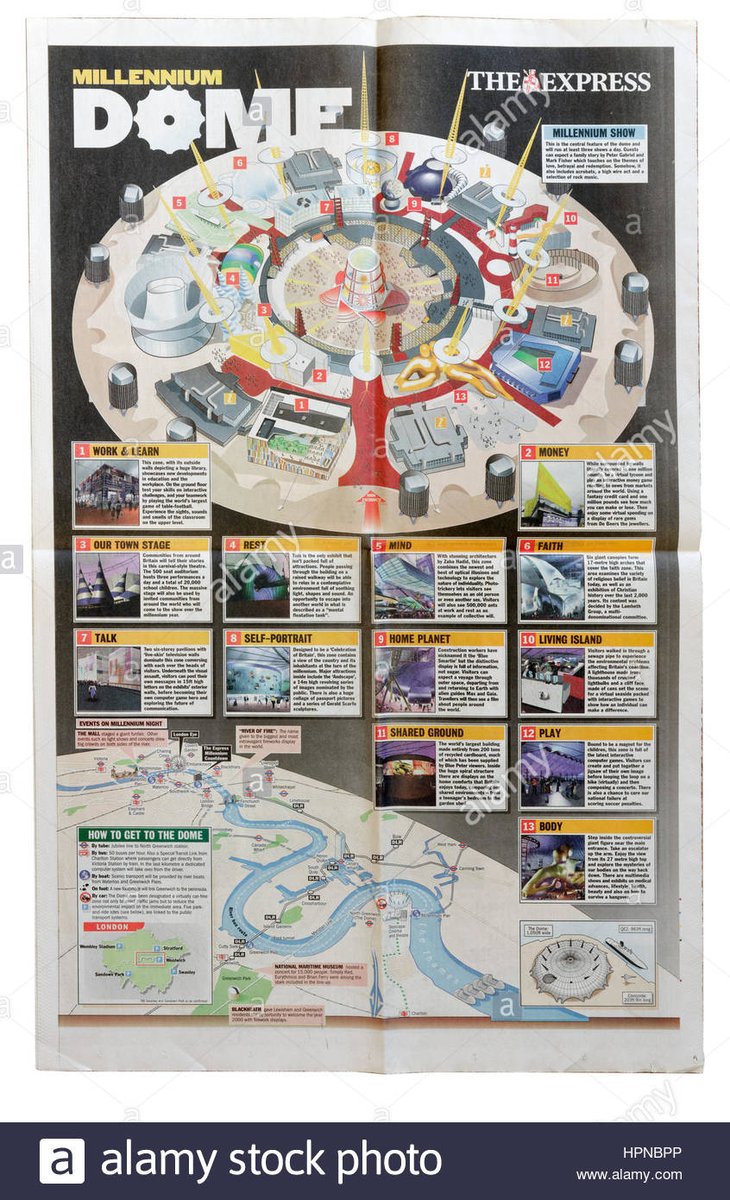

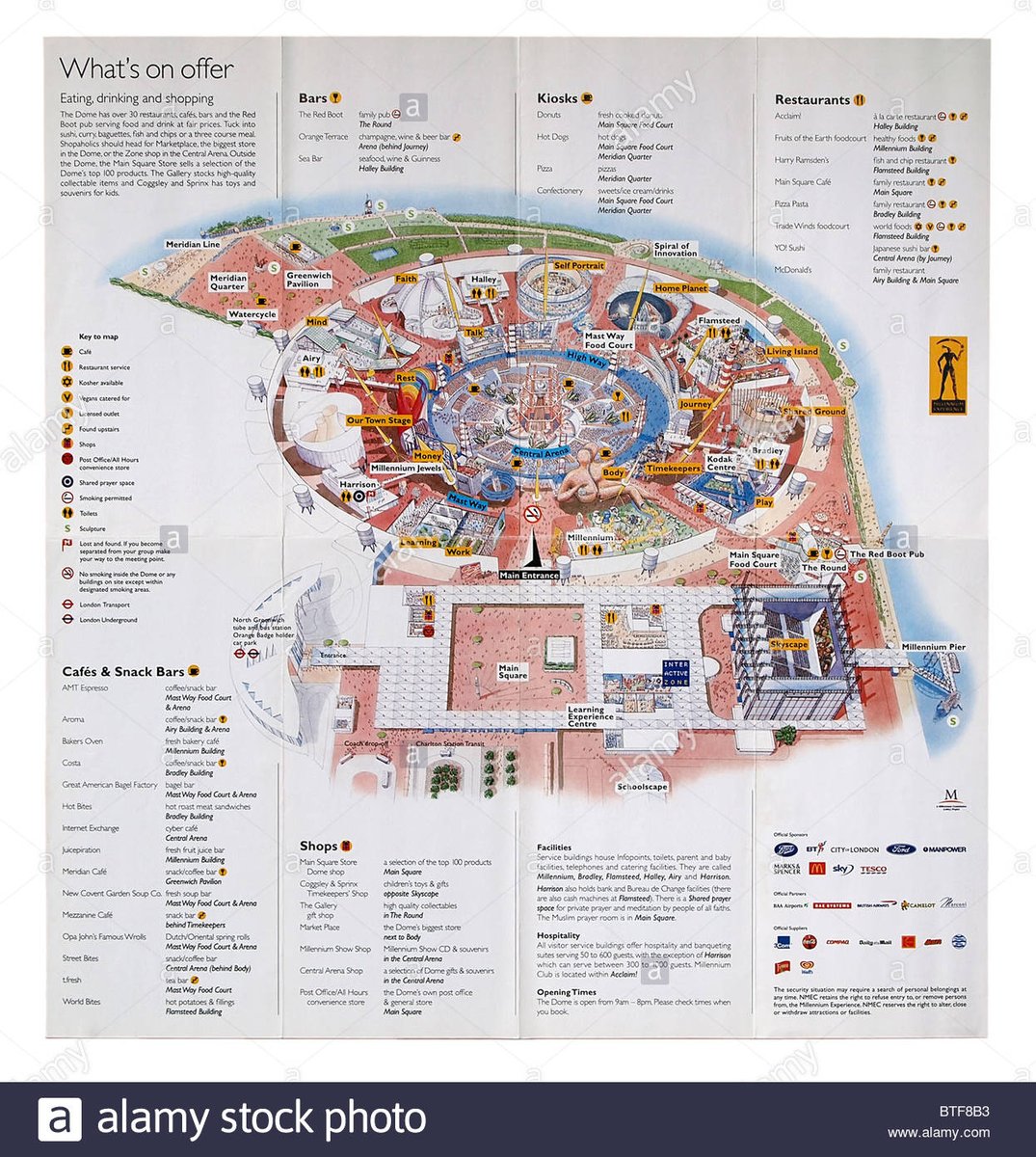

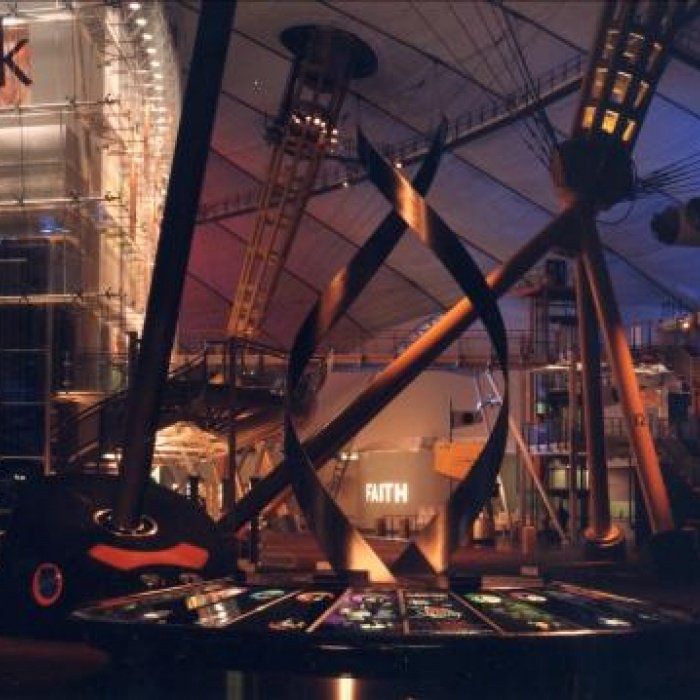

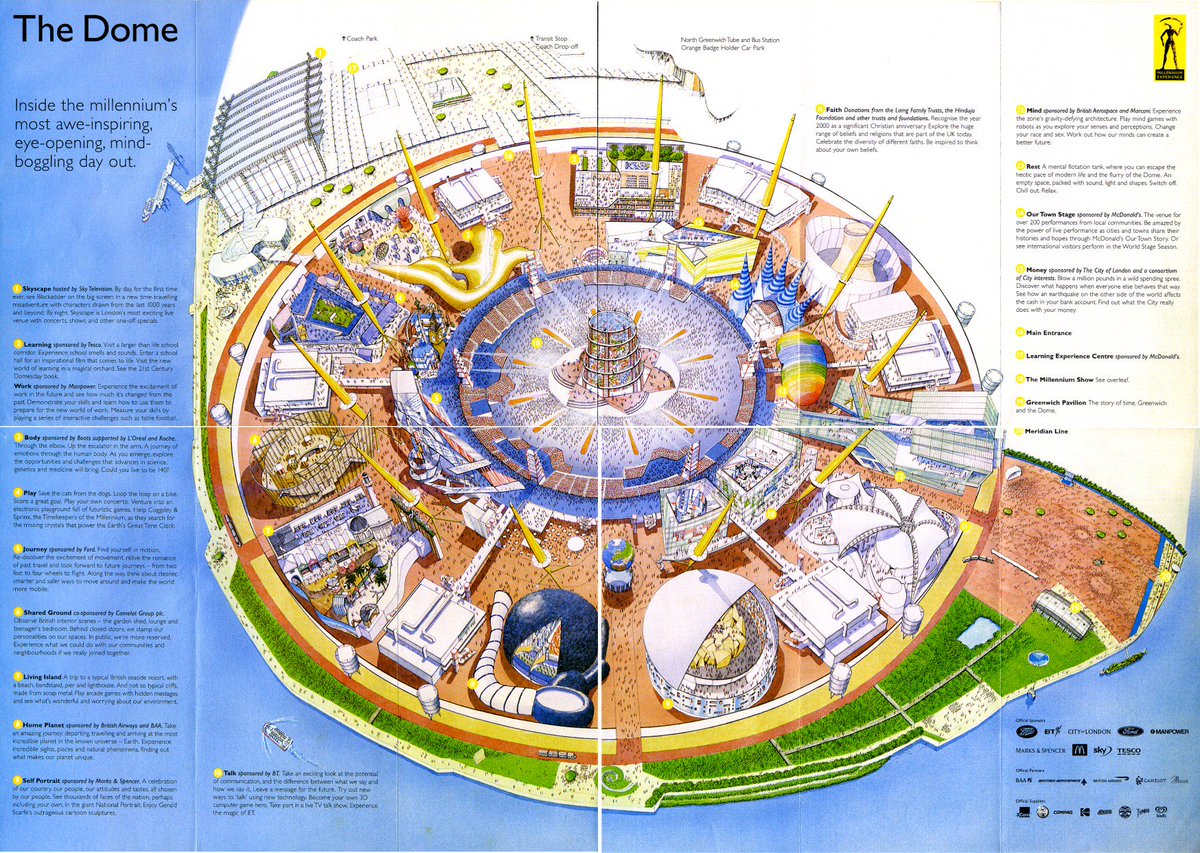

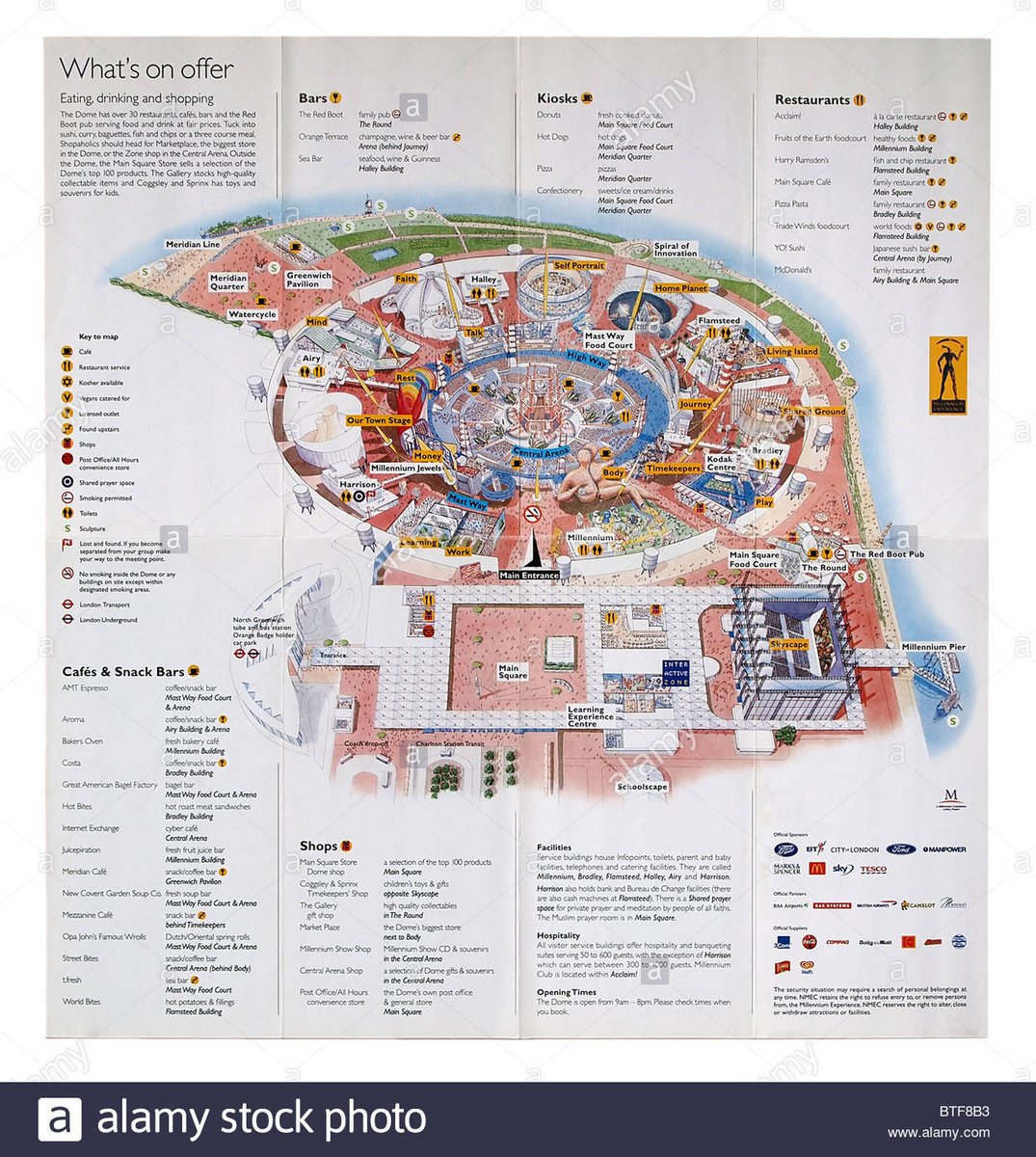

The true focus of the project, though, was what lay inside the dome: the Millennium Experience, a HUGE expo featuring pavilions in the style of a World& #39;s Fair

The Millennium Experience was GARGANTUAN, the most ambitious - and controversial - artificial space ever publicly funded

The Millennium Experience was GARGANTUAN, the most ambitious - and controversial - artificial space ever publicly funded

The Millennium Experience was designed to talk about all corners of British life as the year 2000 approached. Faith, the body, transportation, work, learning, the environment, and more were represented - all tied together by a central stage show.

Let& #39;s walk through it together.

Let& #39;s walk through it together.

And we& #39;re back!

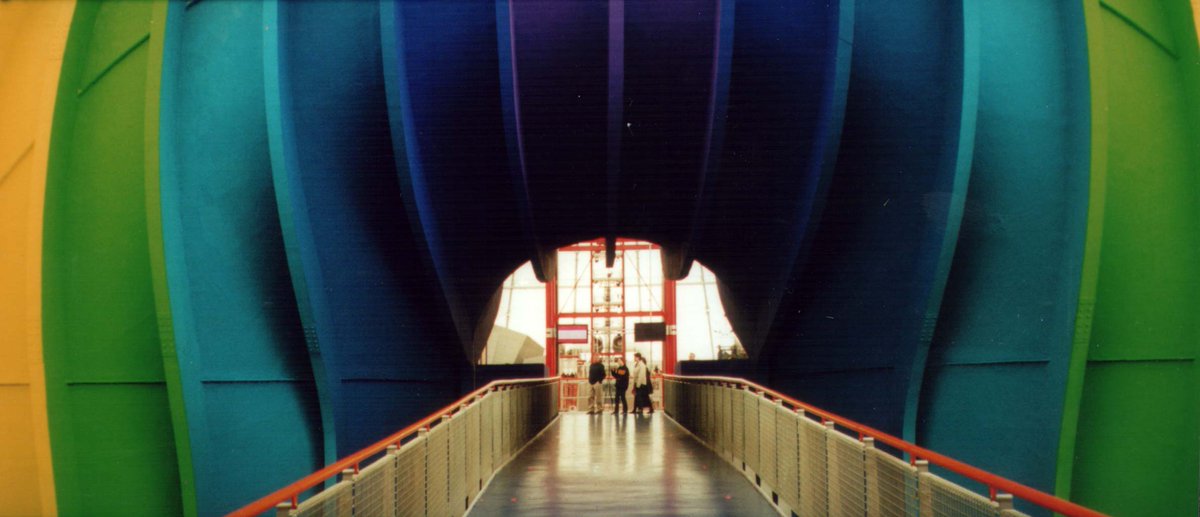

Visitors arrived at the dome from the newly constructed North Greenwich tube station (which required a line extension specifically for the dome). They& #39;d pass various art installations, some kinetic, including the looming Quantum Cloud by Antony Gormley.

Visitors arrived at the dome from the newly constructed North Greenwich tube station (which required a line extension specifically for the dome). They& #39;d pass various art installations, some kinetic, including the looming Quantum Cloud by Antony Gormley.

Around the dome& #39;s exterior were the Millennium Pier - one massive steel pontoon w/ a recycled plastic deck - and Watercycle, a water reclamation system. 50% of the dome& #39;s water use was reclaimed, and the dome served as a notable testbed for research into water-efficient washrooms

Then, there was Skyscape, a massive outdoor cinema + stage meant to serve as a venue. Despite housing the largest screen in London, it only ever showed a short film followup to 80& #39;s BBC comedy Blackadder.

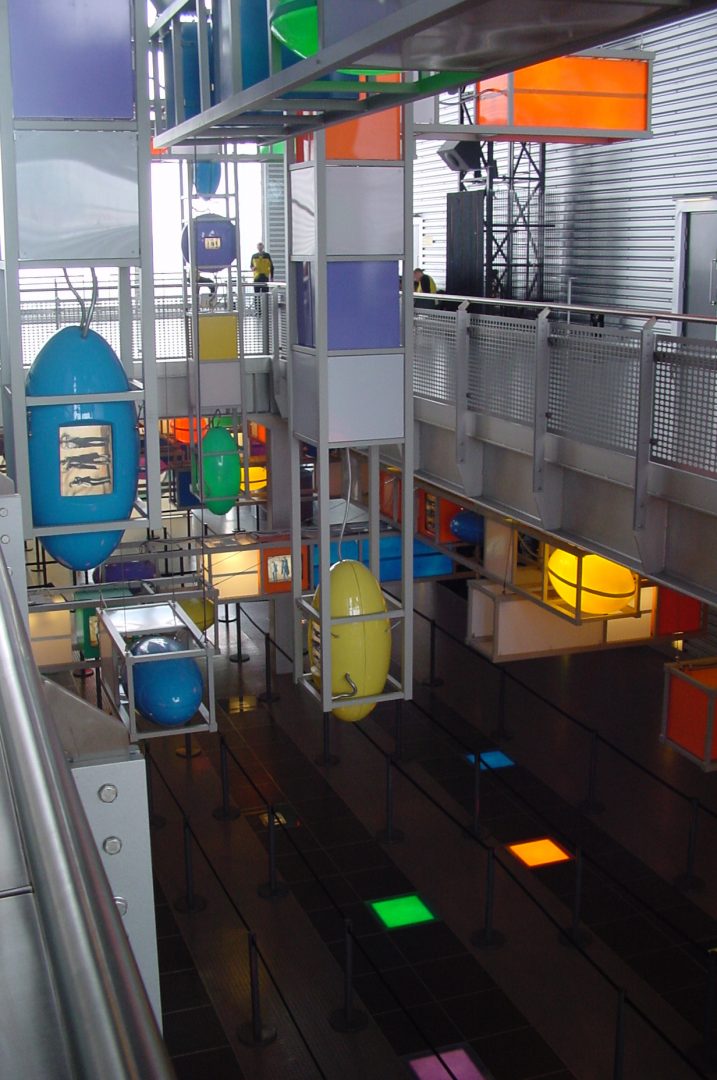

The queue here is VERY y2k/gen x - I particularly love the TV blobjects.

The queue here is VERY y2k/gen x - I particularly love the TV blobjects.

Inside, sixteen (!!) pavilions surrounded the dome& #39;s central theater. In between them, an elevated "highway", linked by washroom/dining areas, allowed for quick transport from one side to another.

We& #39;ll head clockwise on our journey, heading first to Work/Learning.

We& #39;ll head clockwise on our journey, heading first to Work/Learning.

Work/Learning is an excellent starting point for addressing some of the dome& #39;s controversy. For starters, almost all of the dome& #39;s "zones" had corporate sponsors - despite its enormous public funding. These twin zones were sponsored by temp agency Manpower and grocery chain Tesco

Within the Work Zone& #39;s image-shifting exterior walls (think shutter billboards), the sponsor& #39;s influence quickly became apparent. Guests were greeted by robotic hamsters on wheels, and various displays declaring what guests would need to do to "stay employable". Fun.

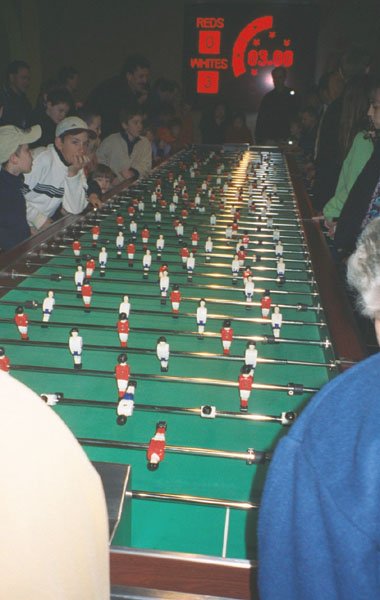

Other features included a "Skills Workshop" (complete w a patronizing "Skills Passport"), an arithmetic game (meant for /children/) to judge their competency for work, and the world& #39;s largest breakroom foosball table

Needless to say, guest reception to this zone was... negative.

Needless to say, guest reception to this zone was... negative.

The adjoining Learning zone wasn& #39;t much less tone-deaf. Guests started in an oversized school hall, with theater "classrooms" that showed a film about learning in the 21st century. To evoke childhood memories, scents like boiled cabbage were pumped into the room.

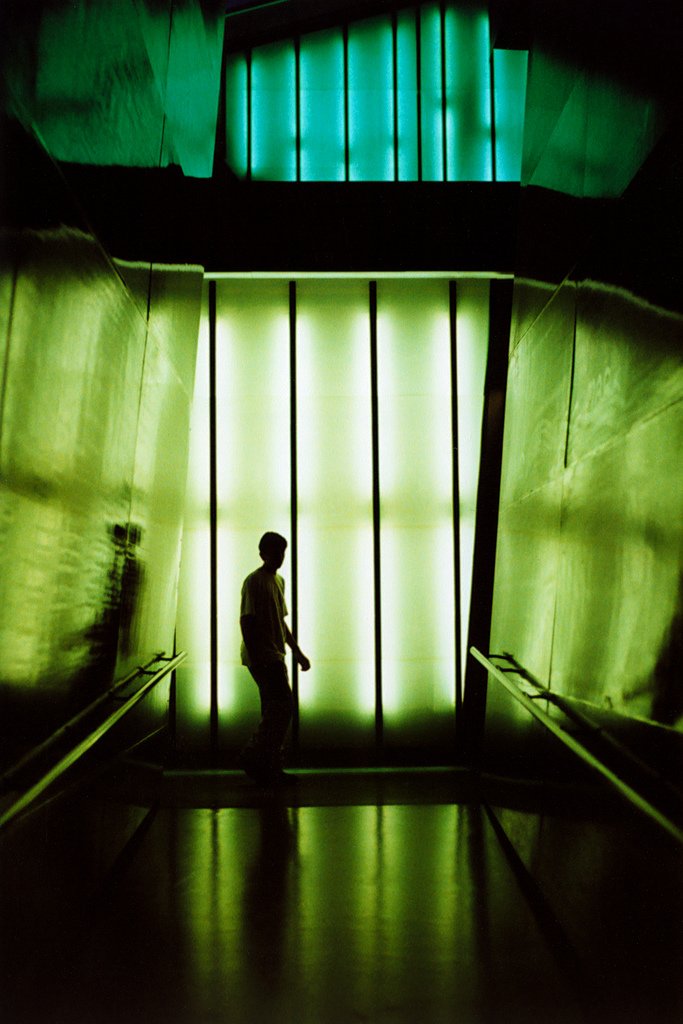

To contrast to the stuffy school halls of yesterday, guests were then transported to the "digital orchard", a visually stunning area filled with table computers that demoed concepts of future interactive learning.

(as you may have noticed, photos of much of the dome are scarce.)

(as you may have noticed, photos of much of the dome are scarce.)

Outside, guests could browse Tesco Schoolnet 2000, an early effort to make educational webpages available to schools around the UK.

The Learn zone, while better received than Work, showcased another glaring issue - computer-based sections of the zones were often out of order.

The Learn zone, while better received than Work, showcased another glaring issue - computer-based sections of the zones were often out of order.

Next, we reach the Money Zone, sponsored by the Corporation of London. Guests entered via a glass hallway lined with £1 million in £50 notes (sadly not pictured).

This zone& #39;s design is deliciously of the era, w graphic design that would be right at home on a big beat album cover

This zone& #39;s design is deliciously of the era, w graphic design that would be right at home on a big beat album cover

Guests could invest in play stock (calculated via real time index values), or play a game on shopping cart-shaped PCs to see how quickly they could spend £1 million.

To the dome& #39;s critics, many of whom saw it as an extravagant New Labour pet project, this was /not/ a good look.

To the dome& #39;s critics, many of whom saw it as an extravagant New Labour pet project, this was /not/ a good look.

Adjacent to the Money zone was the Millennium Jewels exhibition, sponsored by DeBeers. Featured was one of their most perfect diamonds, the Millennium Star. This area gained notoriety after a botched jewel theft in 2000 that involved a JCB digger smashing through the dome.

Next was Our Town Stage, one of the more favorably reviewed zones of the dome by guests. This stage and exhibition area featured performances, art, writing, etc. by children from every local education authority across the UK, featuring what they liked best about their hometown.

Onwards was Rest Zone, dedicated entirely to giving guests a relaxing place to rest. Through a rainbow gate, guests would enter a huge white expanse filled with light and ambient music - a composition called & #39;Longplayer& #39; by Jem Finer designed to take 1,000 years to fully play.

Next is Mind Zone, another tragic example of the dome& #39;s issues. Designed by the legendary Zaha Hadid, guests would enter (passing by a very out of place and very large boy) to find interactive exhibits on self-awareness, perception, and collective thinking.

When they worked.

When they worked.

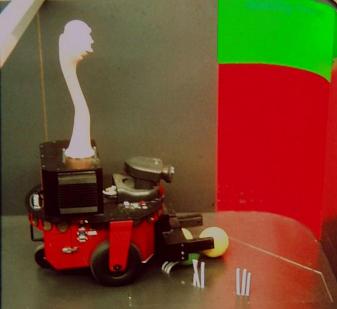

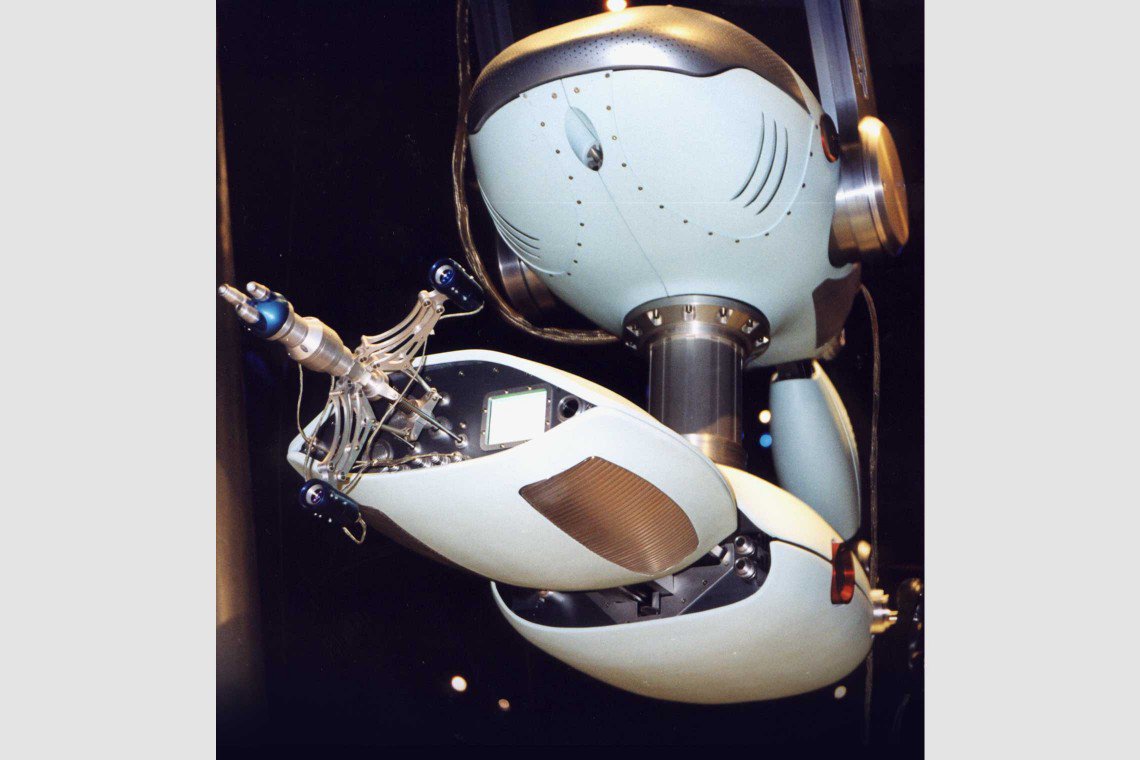

Mind Zone& #39;s first area, the "robot zoo", starred working robots that represented milestones in autonomous intelligence (including Grey Walter& #39;s famous 1940s-era "tortoise")

Within months, due to constant breakdowns, the zoo was replaced entirely by static optical illusions (3rd)

Within months, due to constant breakdowns, the zoo was replaced entirely by static optical illusions (3rd)

Other installations were prone to malfunction - live "brain scans" (done with motion tracking) often gave guests a black screen, and a sculpture called "Smokey Joe" (designed to make a figure visible via infrared camera in a box of smoke) was often devoid of any smoke at all.

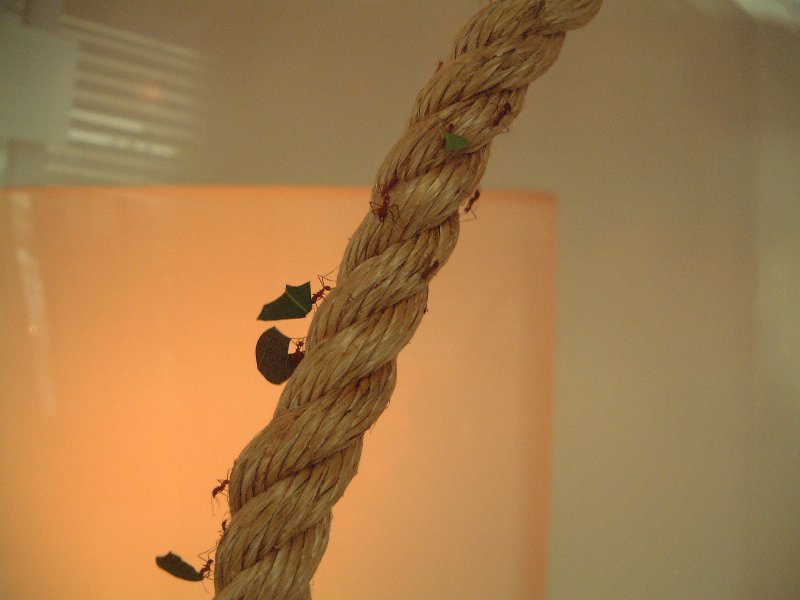

A colony of leaf-cutter ants, as well as a large semi-interactive wrap-around screen called "Plan-It", presented live scenarios showcasing collective thinking, alongside a real-time mapping of the early web. A "neural net creature" showcased early Kinect-like depth camera tech.

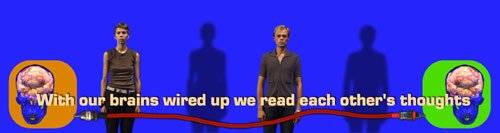

some graphics displayed on the Plan-It screens embody the sort of nebulous, substanceless speculation at the future which left many dome visitors unsatisfied, or even cynical (this will be touched upon later in the thread).

A last notable detail about the Mind Zone - its sponsors were GEC, British Aerospace, and Marconi, which are all arms manufacturers. By this point in their trip, some guests felt unease about the sponsors of these zones, and how much sway they had over their content.

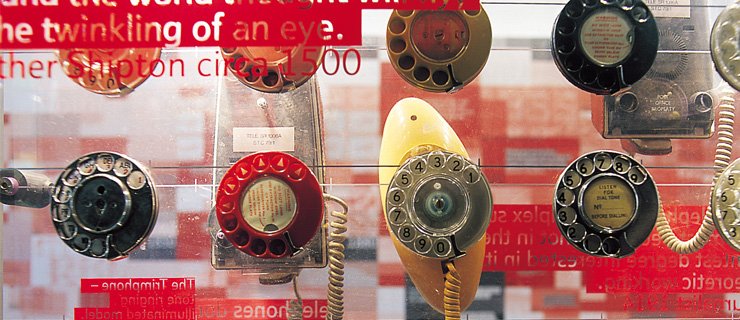

These concerns might continue to mount as guests reach the Talk Zone, sponsored by British telecom BT. This zone, dedicated to the future of digital communication in the 21st century and beyond, had some of the most bizarre corporate content yet.

The zone featured some examples of telecommunication technology from throughout history, including phones and early computers. Here, like the rest of the dome, guests were bombarded with open-ended questions about the future, while being presented with few answers or ideas.

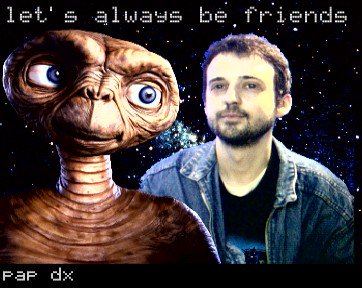

Oh yeah. And ET was there.

Yup. BT, who had been running a "phone home" ad campaign with the extraterrestrial, felt compelled to make him the focal point of the Talk Zone. Guests could get their picture "taken" with ET, and write an email postcard with him.

See a pattern yet?

Yup. BT, who had been running a "phone home" ad campaign with the extraterrestrial, felt compelled to make him the focal point of the Talk Zone. Guests could get their picture "taken" with ET, and write an email postcard with him.

See a pattern yet?

For reference, here& #39;s one of the ads BT was airing at the time. Note the Millennium Dome itself, clearly visible in the background, at the end. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0YIZpwKlqE">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

The Faith Zone is an interesting case: the only main Zone with no sponsor (for reasons to be revealed). It housed a timeline of Christianity in Britain, a "buy a prayer" machine (60p per prayer), and a James Turrell "reflection space" called Night Rain (sadly not pictured).

The lack of a sponsor for Faith Zone was due to it coming under public criticism early in planning. Religious leaders found its inclusiveness to be "too politically correct", and others (ironically) found it too Christianity focused. As a result, the zone felt barren and static.

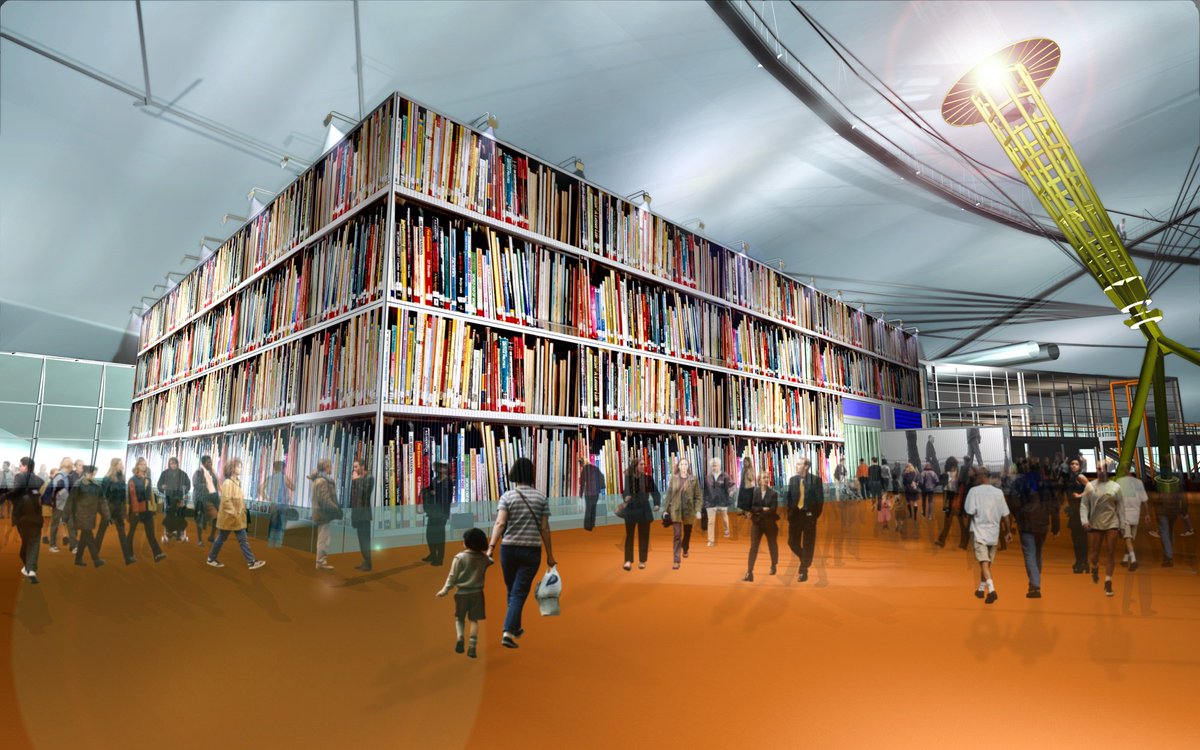

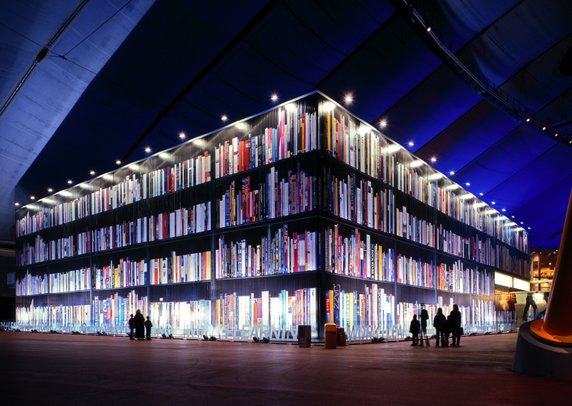

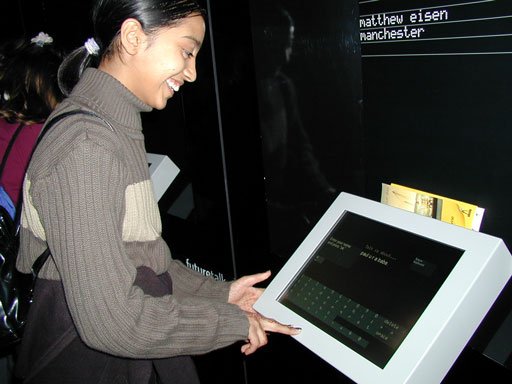

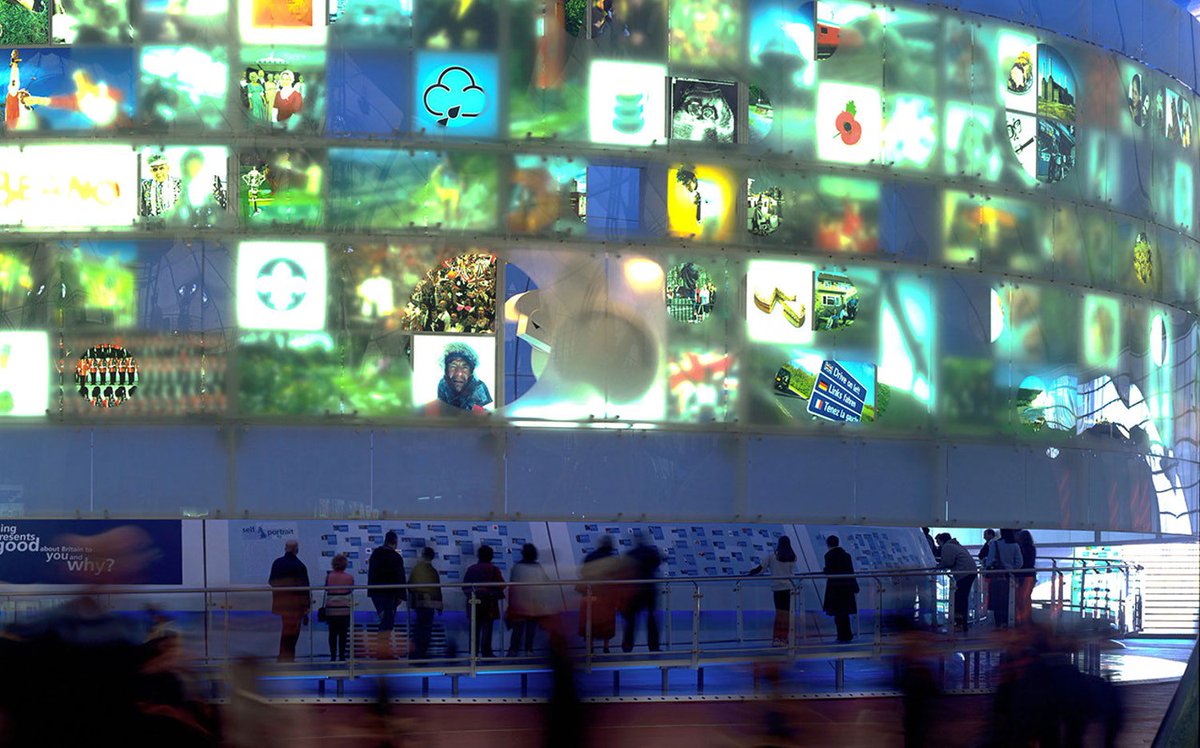

The Self-Portrait Zone, sponsored by retailer Marks and Spencer, was meant to serve as a self-reflection of the state of Britain circa 1999. It was encased by the "ANDscape", a giant "kinetic portrait collage" made up of hundreds of interviewed British citizens.

Self-Portrait also featured several sculptures by political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe. With titles such as The Racist, The Couch Potato, The Thug, and Traditional Cool Britannia (caricaturing Tony Blair), these pieces were a FAR CRY from the nebulously optimistic mood of the dome.

Home Planet, sponsored by British Airways, was the only "ride" in the dome. A revolving theater ride (like Disney& #39;s Carousel of Progress) where two aliens guided riders (Star Tours style) through deep space to a beautiful planet - only to reveal that it was earth all along. sigh.

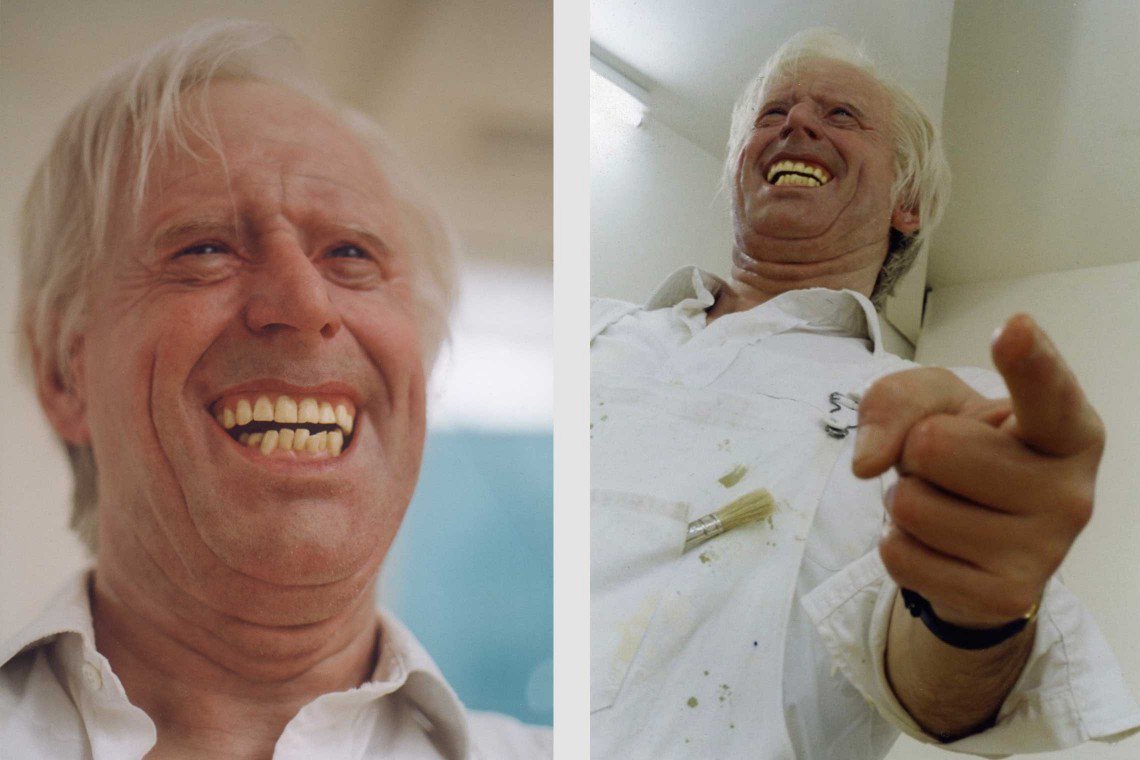

The coolest thing about Home Planet is that, while it did use screens for its space travel segments, all of its landscapes were life-size dioramas that used practical effects. Here are some WIP shots for some of the landscapes, compared to another shot of the finished product!

The Living Island zone, completely concealed from outside view, had guests journey through a "tunnel of love" into a fully enclosed model of a British island resort - though not all was as it seemed. The entire area was built with recycled materials, with an ecological theme.

Living Island featured a boardwalk full of midway games, each with a hokey environmental parable. Though the content left guests dissatisfied, the zone& #39;s design was fairly impressive. The lighthouse, visible over the zone& #39;s (cardboard) walls, was made entirely from lightbulbs.

Journey, sponsored by Ford, was the most museum-like of all the zones, and covered a general history of transportation, while offering some insights into its potential future (drawing from pop culture or otherwise).

Journey, like other areas of the dome, let guests share their thoughts about the future of transportation (though what, if anything, was ever done with those responses is lost to time).

Oh, it also had James Bond& #39;s boat from The World Is Not Enough. British, I guess.

Oh, it also had James Bond& #39;s boat from The World Is Not Enough. British, I guess.

Shared Ground, featuring BBC children& #39;s show Blue Peter, had walls made almost entirely out of cardboard donated by BBC viewers (designed by Shigeru Ban). It featured mock streets and alleys, where kids could record their thoughts about their neighborhoods.

Their recorded responses were stored in a time capsule set to be opened (allegedly) in 2999, whose contents could be seen on its second floor.

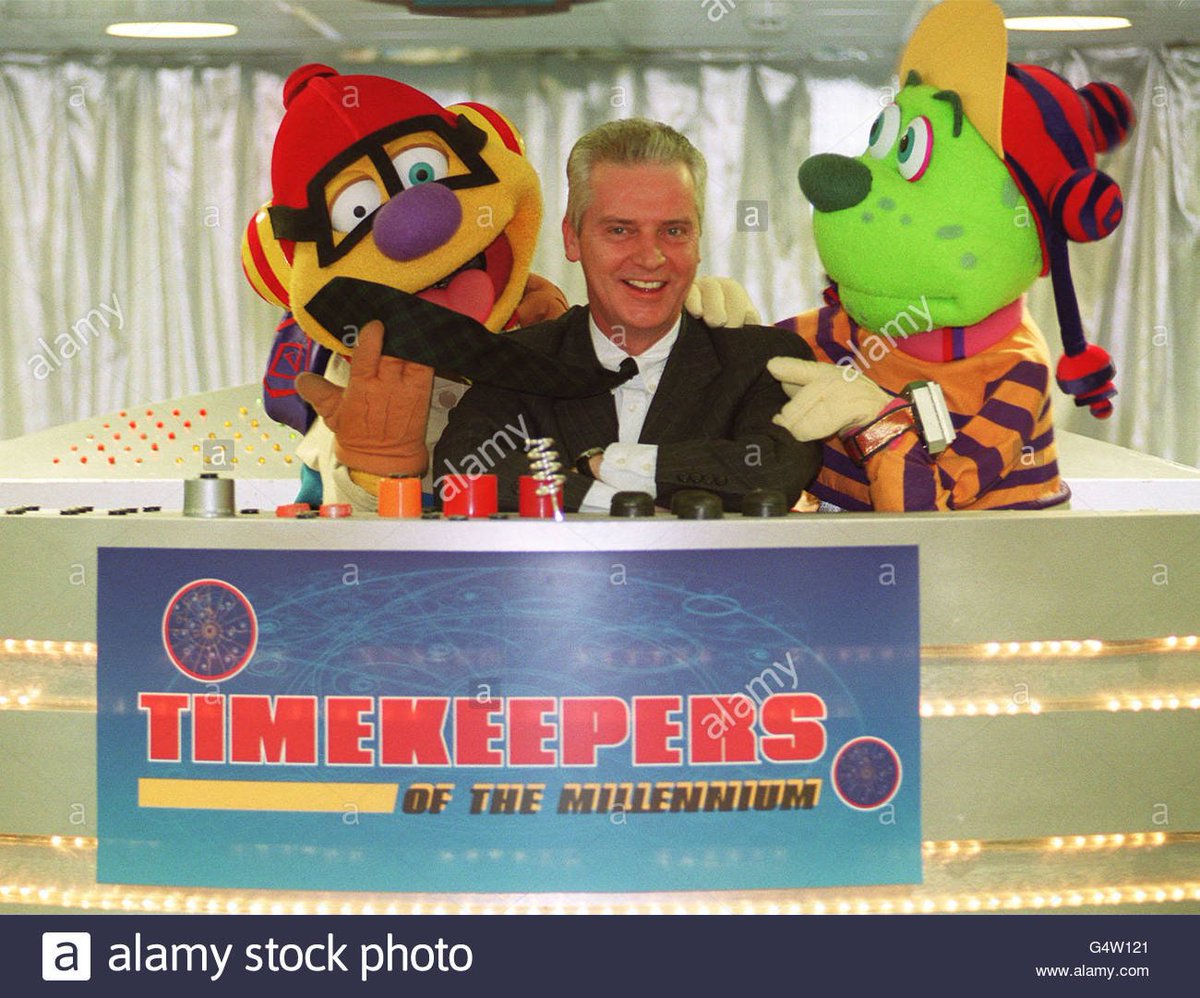

Timekeepers, one of the most popular areas of the dome, was more or less a jungle gym, ditching philosophical waxing in favor of some foam ball warfare (air cannons and all). It starred Coggs and Sprinx, two muppet-like characters, who had their own (now lost) miniseries on CiTV.

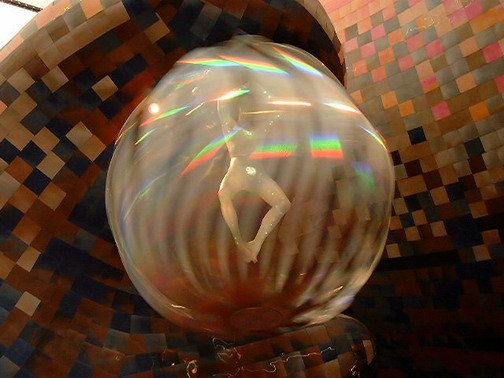

Similarly, Play Zone was a place where the name said it all. It sported tons of large game installations - "SofaVision" wrap-around simulators (similar to Disney& #39;s CAVE system used at DisneyQuest), the "Iamoscope" dynamic digital kaleidoscope, and the "Reaktor Batak" reflex game.

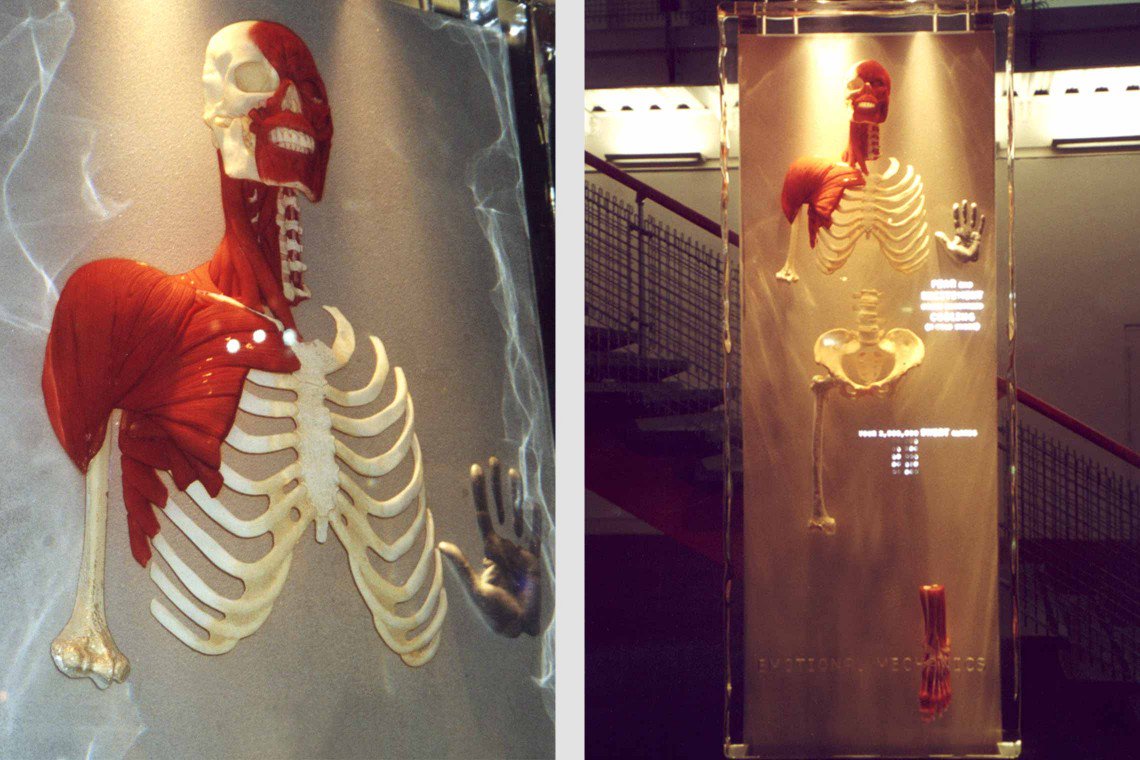

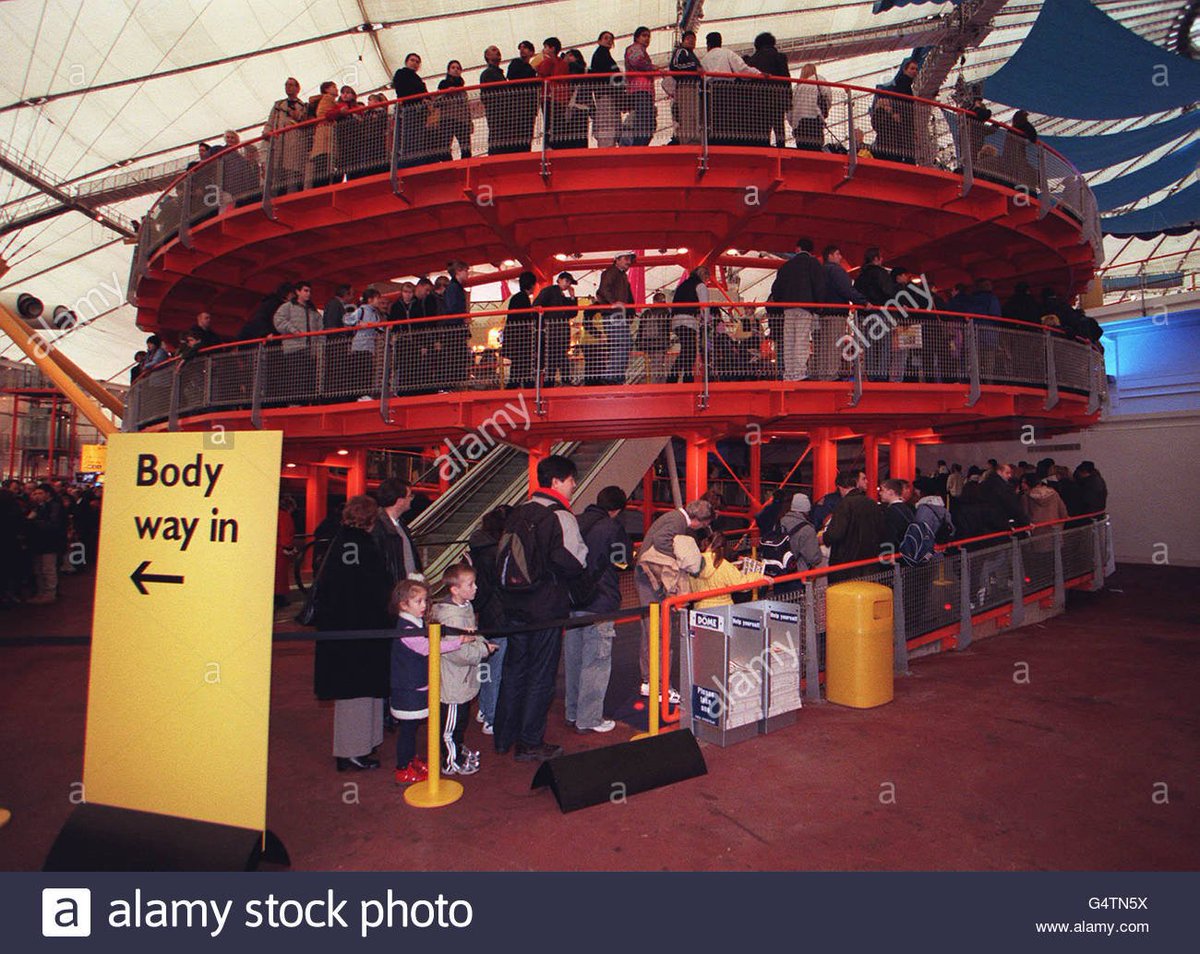

Our clockwise journey brings us, finally, to the Body Zone, marketed as the star attraction of the dome. This towering pavilion, shaped like two adjoined human bodies holding a third in their hand, was sponsored by lab tech company Boots.

Around the Body Zone were various installations, such as anatomical models encased in perspex blocks, and interactive kiosks. Like the rest of the dome, the sponsor& #39;s influence was in full sway here, to the ire of some guests.

The eerie realism of the Body Zone continued as guests entered the queue, where realistic human models were mounted on scaffolding from the rafters.

I feel I should give a CW: gore tag for the following tweets. It gets pretty nasty.

I feel I should give a CW: gore tag for the following tweets. It gets pretty nasty.

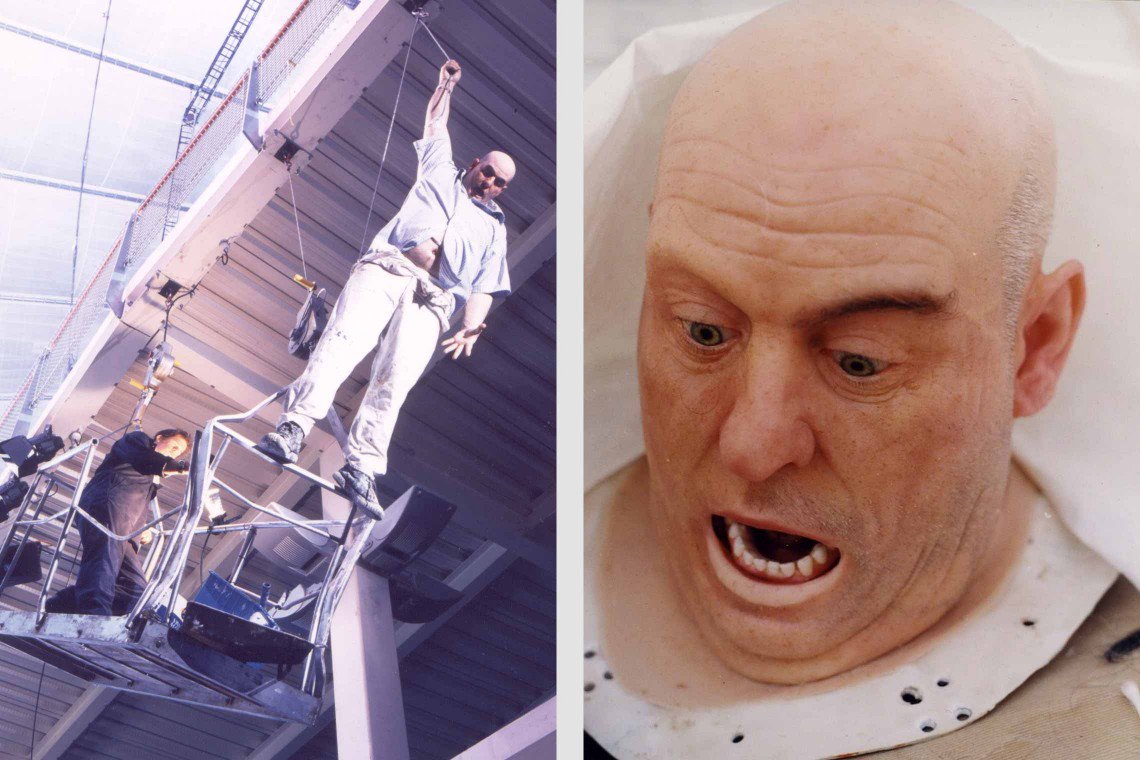

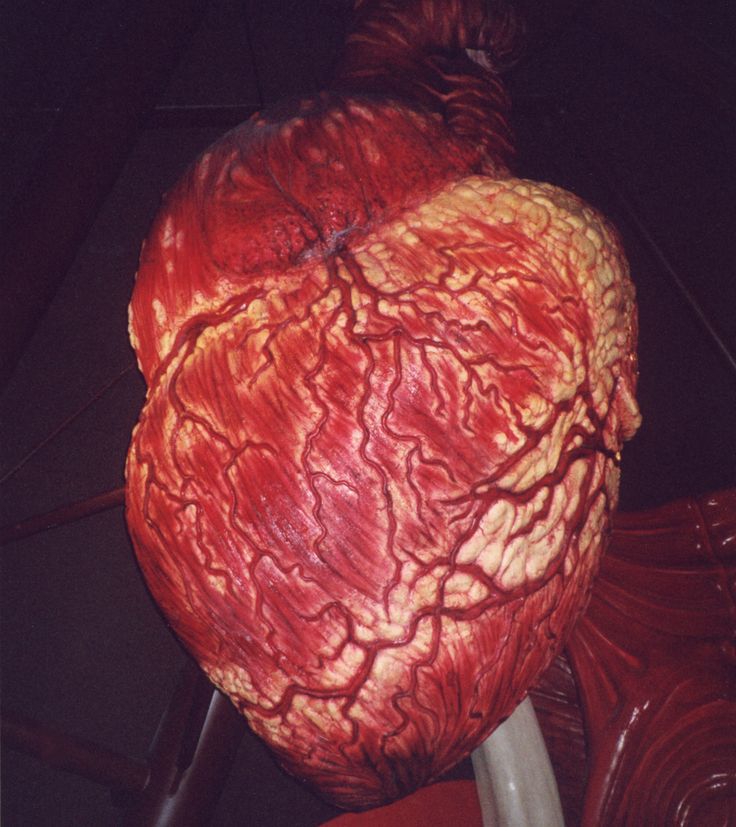

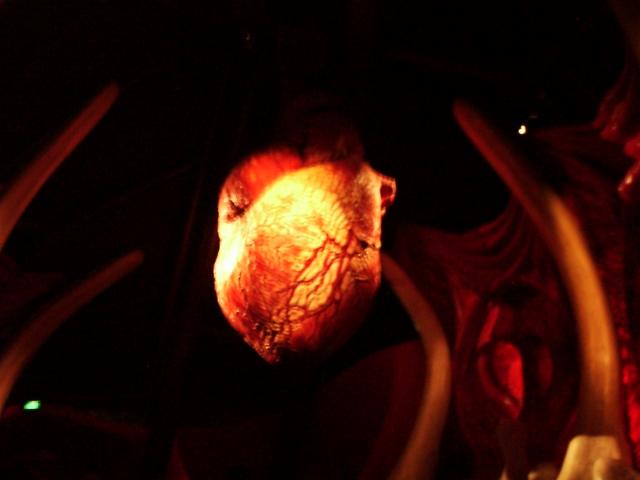

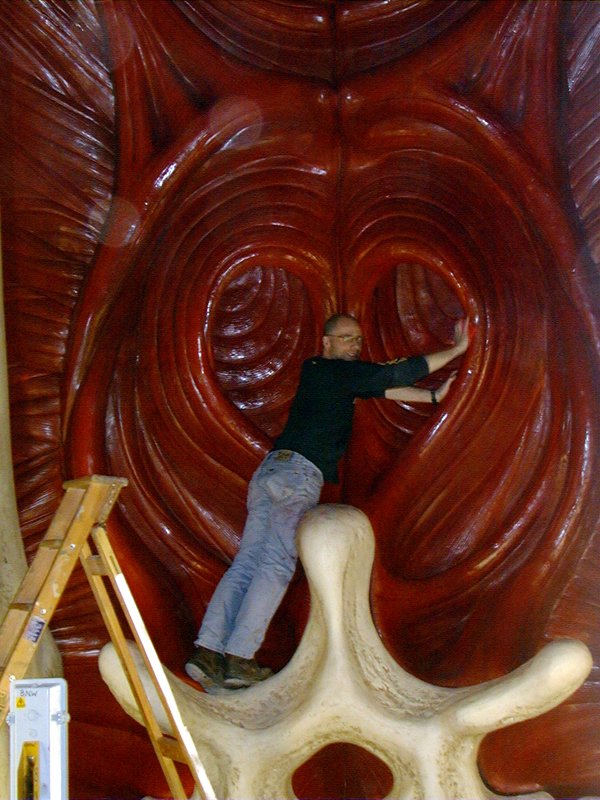

Guests ascended into the bodies through an escalator at the knee, going past a gigantic beating human heart. Yknow, in the knee. (also, here& #39;s a WIP shot of the ribcage it resided in).

Inside, guests were greeted by........ uh..... flesh. Walls of flesh.

Complete with uh. Animatronic. Pubic lice.

as in, they moved.

Complete with uh. Animatronic. Pubic lice.

as in, they moved.

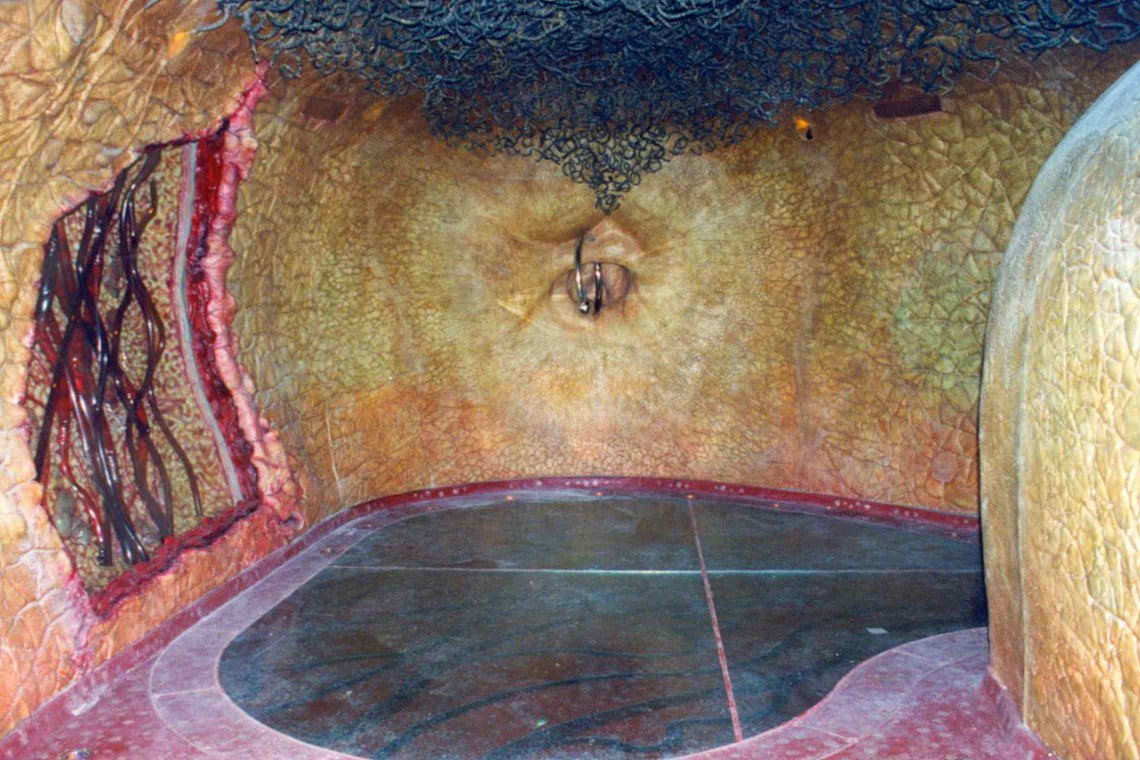

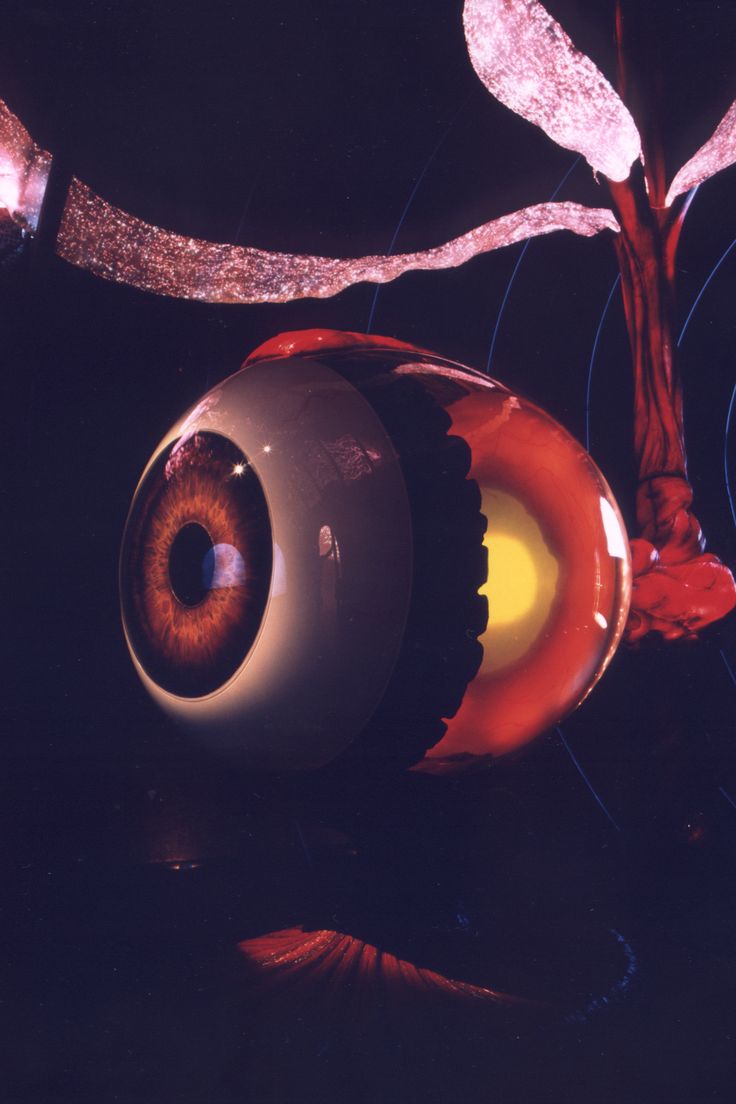

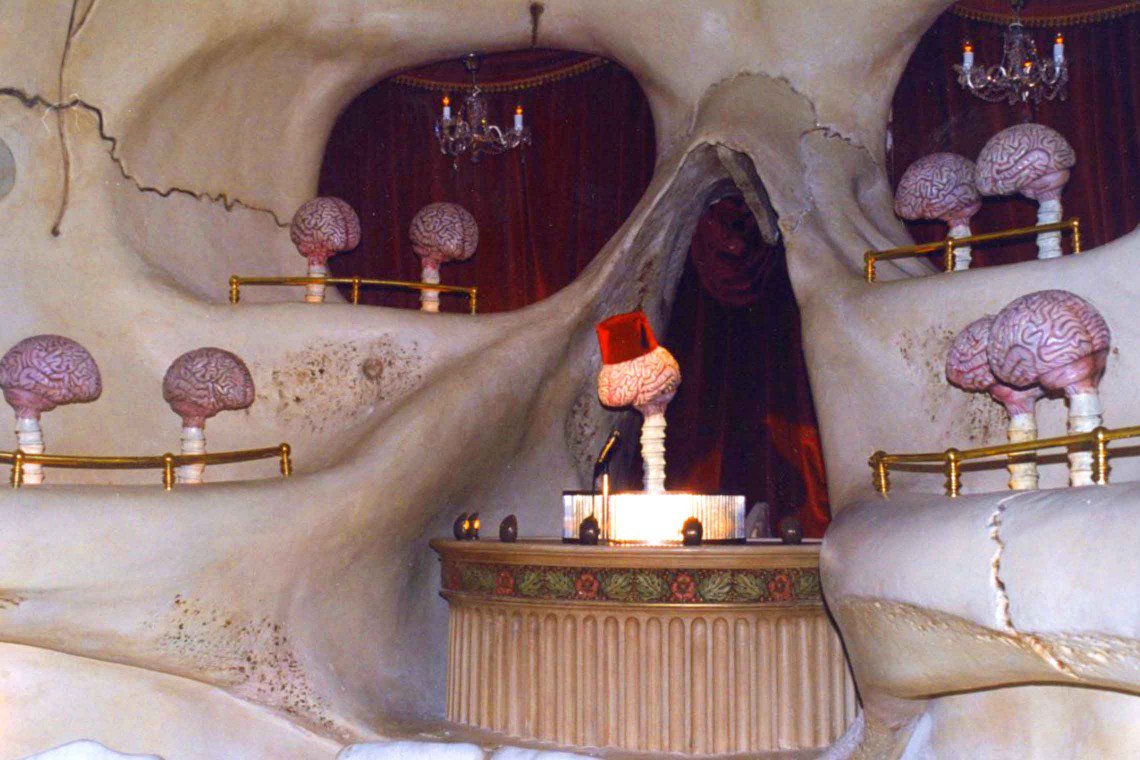

Pas the uh... flesh walls... was an eyeball projected an educational film, and a bunch of brains that did Tommy Cooper impressions with one of them wearing a fez.

here is also Queen Elizabeth, likely feeling very similar things to what you& #39;re feeling right now.

here is also Queen Elizabeth, likely feeling very similar things to what you& #39;re feeling right now.

Exiting the body, guests could interact with some concepts for future medical equipment, such as a "parasite scanner".

Overall, guests described the Body Zone experience as bewildering. This was compounded by the area& #39;s infamously long, poorly managed queues (1 hour+!)

Overall, guests described the Body Zone experience as bewildering. This was compounded by the area& #39;s infamously long, poorly managed queues (1 hour+!)

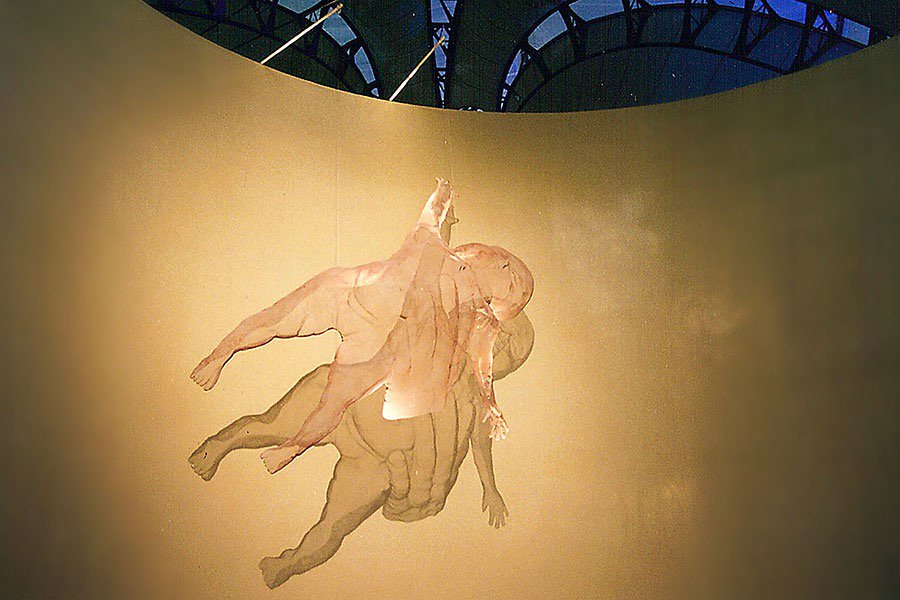

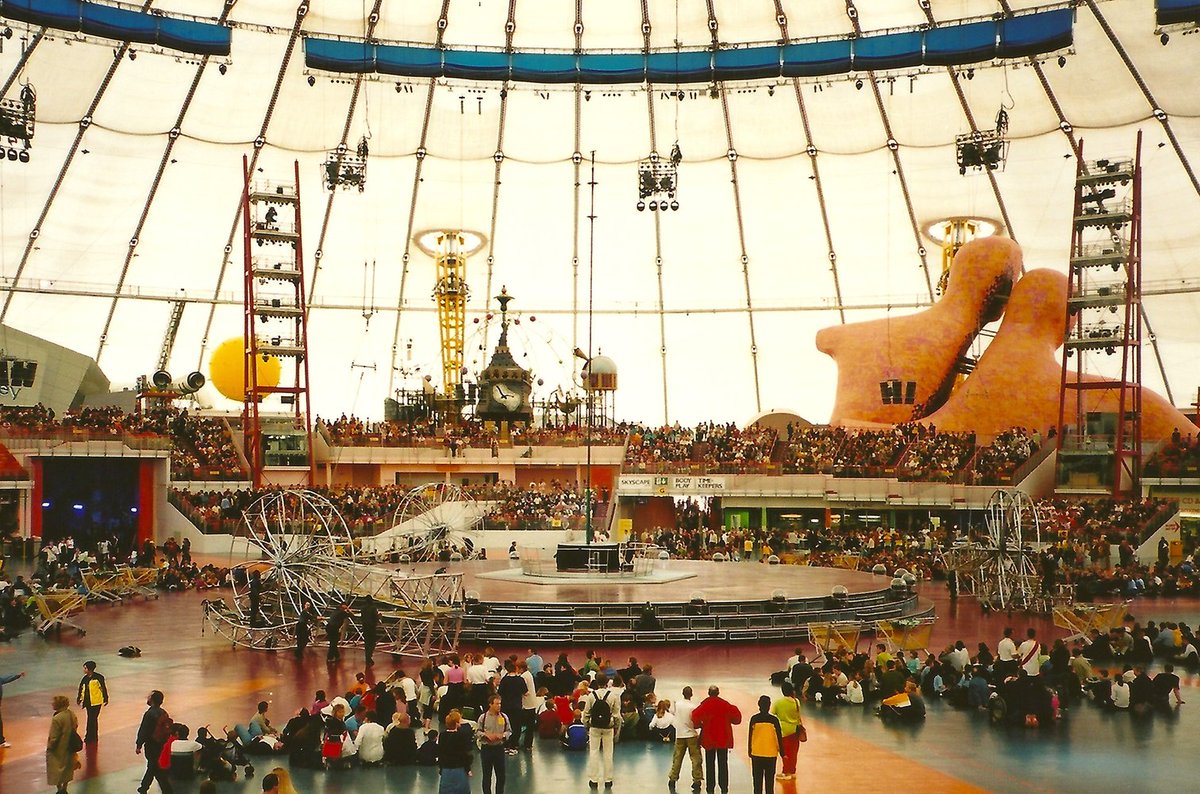

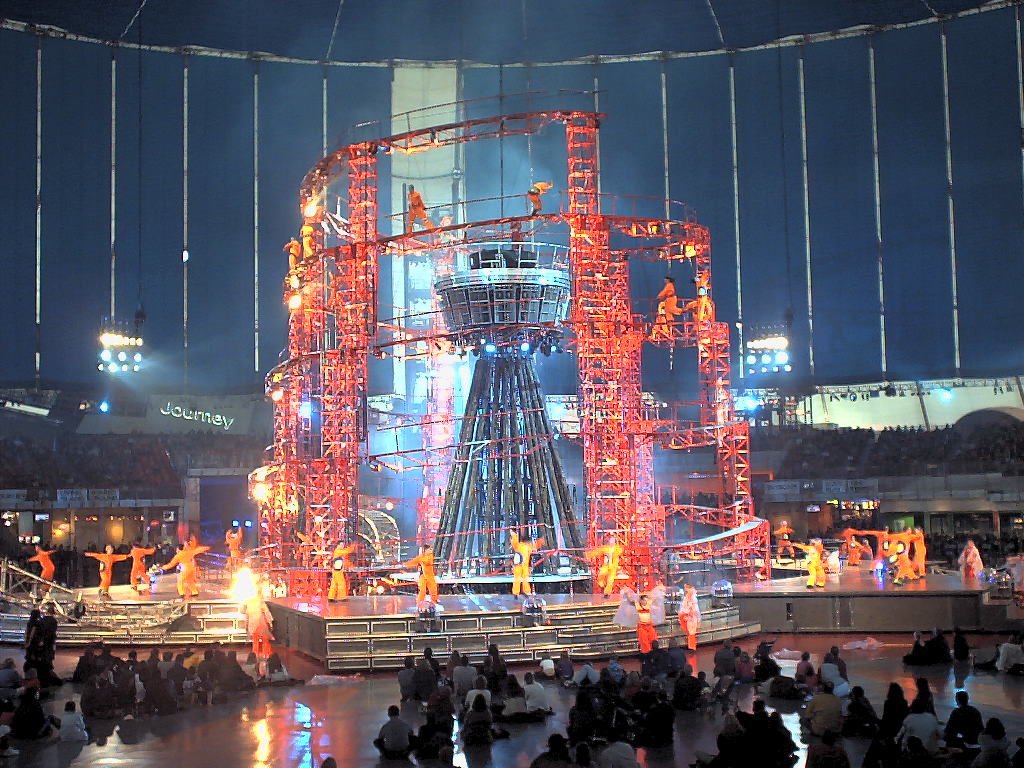

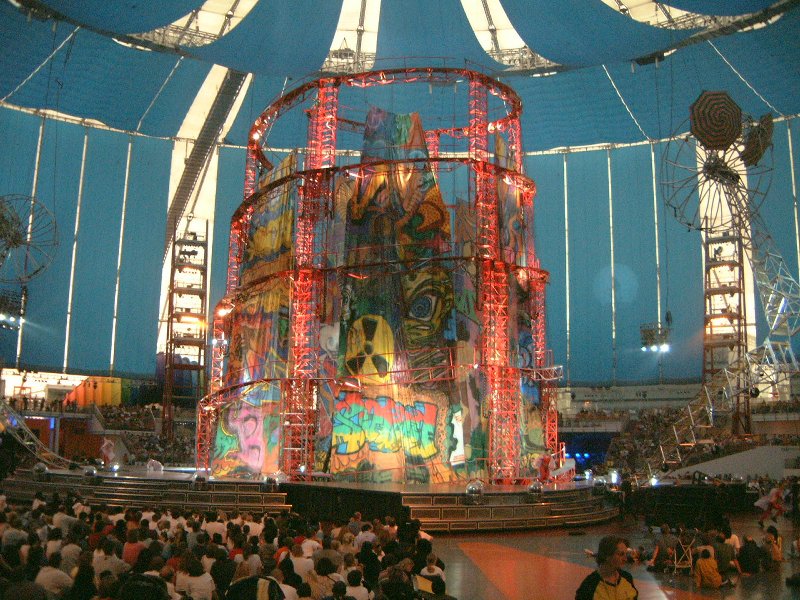

16 zones, with radically different approaches and content. It was up to the central performance, the Millennium Show (aka OVO - not the Cirque Du Soleil show of the same name), to unite all of them into one vision for the new millennium.

Did it? Not really. But it looked cool.

Did it? Not really. But it looked cool.

The show was designed by Mark Fisher and composed by Peter Gabriel (yes, that one).

With no dialogue, it told a Romeo & Juliet style story between warring civilizations of the earth and sky, and two children, Sophie and ......... Skyboy.

With no dialogue, it told a Romeo & Juliet style story between warring civilizations of the earth and sky, and two children, Sophie and ......... Skyboy.

The show utilized wire acrobatics, massive flame jets, and culminated in building a tower from the earth to the sky, made of giant graffiti chunks of concrete.

Guests complained that the show& #39;s plot was barely coherent, and judging from footage, I have to agree with them.

Guests complained that the show& #39;s plot was barely coherent, and judging from footage, I have to agree with them.

As flimsy as the premise is, Peter Gabriel& #39;s soundtrack SLAPS (it was released later as OVO). This has gotta be my favorite track, featuring some juicy percussion and Gabriel& #39;s finest numetal growl. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ei6fJ10zjlc">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

The Millennium Show is a good place to wind down our journey through the dome. It represents the dome& #39;s contents well - high budget, full of artistic ambition, but two steps short of having enough focus to be called great.

But what did the public think of the dome?

But what did the public think of the dome?

The short answer is that the dome was the subject of negative media coverage and public opinion from the getgo, long before it opened, until its closing, and even a fair deal after.

The reasons why are rather complicated. Let& #39;s go through them step by step!

The reasons why are rather complicated. Let& #39;s go through them step by step!

The first kicker, that need to be established before anything else:

The Millennium Experience, and all of its contents, were only designed to be open for one year& #39;s time, from December of 1999 to December of 2000. This created MANY expectations for the project that were not met.

The Millennium Experience, and all of its contents, were only designed to be open for one year& #39;s time, from December of 1999 to December of 2000. This created MANY expectations for the project that were not met.

On top of this, the dome was heavily advertised as "One Amazing Day"& #39;s worth of content. However, due to the long and disorganized queues, that often proved impossible.

This, combined with the year-long lifespan, made guests feel as if they had to rush through their experience.

This, combined with the year-long lifespan, made guests feel as if they had to rush through their experience.

If they rushed, they& #39;d have a hard time finding anywhere to sit. Other than Rest zone, which was often crowded, there was little to no public seating available, save for a massive McDonald& #39;s on the dome& #39;s outer rim. This was seen as a deliberate decision by some cynical critics.

This was, of course, for those who could even visit the dome. Unless you took the newly extended tube to the North Greenwich station, parking was a nightmare, as was arriving by bus. Media and public outcry alike slammed both the govt and NMEC for not providing contingency.

Another thorn in the dome& #39;s side was its image problem. Was it a theme park? Was it a museum? It wasn& #39;t sure, and that left nobody satisfied. Those who came seeking thrills were disappointed, and those who came seeking museum-style exhibits were jaded by the heavy corporate slant

The awkward marriage between the public and private sector in the dome& #39;s implementation brings us, finally, to the elephant in the room - the cost.

By the time of its closure, the entire project cost £789 million - £1.3 BILLION ($1.7 BILLION) adjusted for inflation.

By the time of its closure, the entire project cost £789 million - £1.3 BILLION ($1.7 BILLION) adjusted for inflation.

By comparison, the Wizarding World of Harry Potter in Orlando, FL - seen as one of the world& #39;s most elaborately detailed theme parks - cost USD $456 million in 2014 between BOTH of the Florida parks.

This price tag, especially for a YEAR-LONG exhibition, was seen as an albatross for Tony Blair& #39;s New Labour legacy.

But it gets worse. Only £628 million - £1.05 billion/$1.4 billion in 2018 - was public money. The rest came from corporate sponsorship.

But it gets worse. Only £628 million - £1.05 billion/$1.4 billion in 2018 - was public money. The rest came from corporate sponsorship.

The Millennium Dome& #39;s full financial and political collateral is too long to list. Peter Mandelson, the public face of the dome, resigned mid-construction, embroiled in an ethics scandal. NMEC rarely communicated with the govt, and was rumored to be insolvent for much of 2000.

Visitors to the dome fell far short of the 12 million expected to make it profitable.

Overbudget, underattended, and below expectations, the dome was, by all accounts, a failure.

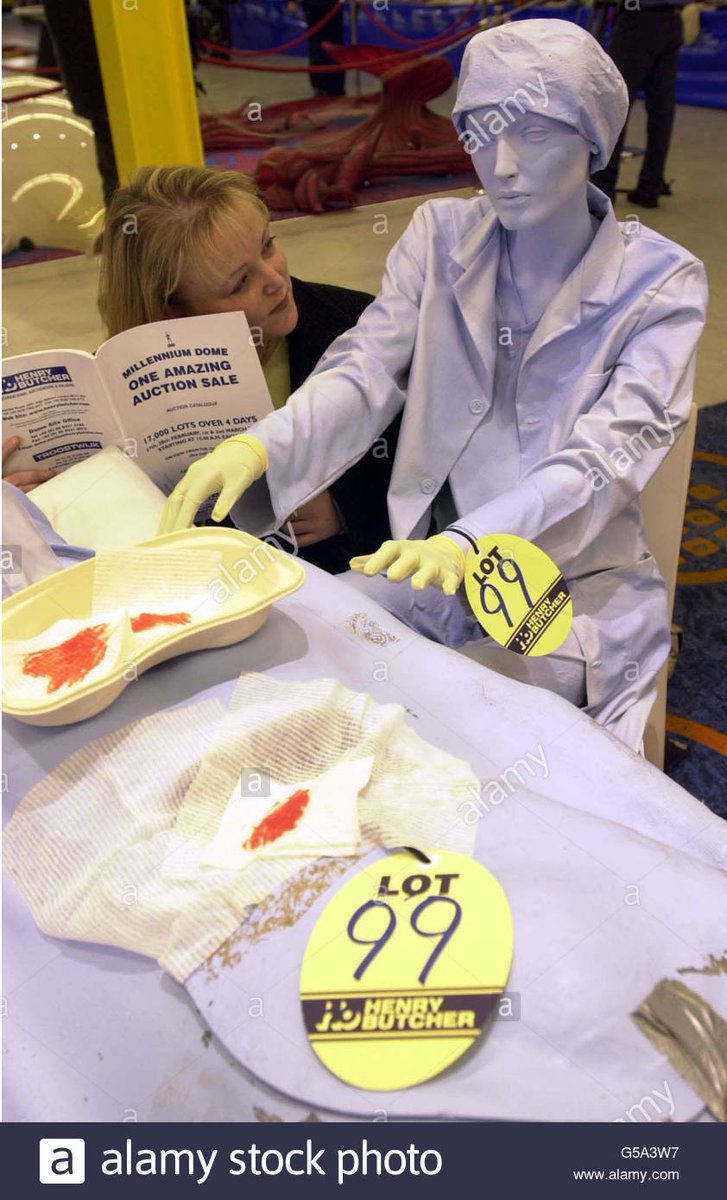

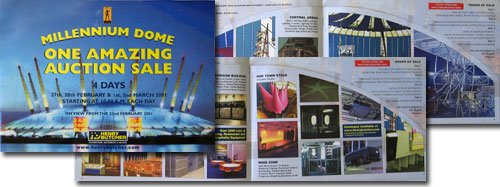

After the show ended, its pieces were either auctioned or destroyed.

Overbudget, underattended, and below expectations, the dome was, by all accounts, a failure.

After the show ended, its pieces were either auctioned or destroyed.

After the show was over, the dome sat largely abandoned. It was used seldom - for an indoor skating rink in 2003, for an Tutankhamen exhibit in 2007.

It wouldn& #39;t be until later in 2007 that a permanent tenant would occupy the dome - the O2 Arena, a multi-purpose indoor stadium.

It wouldn& #39;t be until later in 2007 that a permanent tenant would occupy the dome - the O2 Arena, a multi-purpose indoor stadium.

While researching the dome, I couldn& #39;t help but think of EPCOT, very much an American sibling. I found it funny that while Americans welcomed such a place with open arms, Britain would have none of it.

Is the publicly funded construction of an artificial space doomed to failure?

Is the publicly funded construction of an artificial space doomed to failure?

The Guardian& #39;s @RowanMoore doesn& #39;t think so, and neither do I. In this article, he talks about some of the other Millennium Commission projects - some of which, such as the Eden Project in Cornwall, met with success.

So, what can we learn from the Dome? https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/nov/02/national-lottery-funding-buildings-won-jackpot-architecture-hits-and-misses">https://www.theguardian.com/artanddes...

So, what can we learn from the Dome? https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/nov/02/national-lottery-funding-buildings-won-jackpot-architecture-hits-and-misses">https://www.theguardian.com/artanddes...

#1: Keep the corporate and public wires uncrossed.

The Dome’s crippling image problem came from a combo of huge govt investment and ever-present corporate branding - a neoliberal match made in hell. A public project, whatever its purpose, ought not to prioritize private interest

The Dome’s crippling image problem came from a combo of huge govt investment and ever-present corporate branding - a neoliberal match made in hell. A public project, whatever its purpose, ought not to prioritize private interest

#2: Seek guidance from those you serve.

The Dome’s construction and creative oversight was frustratingly secretive (almost to the point of fraud). If an artificial space is publicly funded, it needs at least a formal, transparent channel for public input.

The Dome’s construction and creative oversight was frustratingly secretive (almost to the point of fraud). If an artificial space is publicly funded, it needs at least a formal, transparent channel for public input.

#3: Focus on making the space accessible.

True for every space, but especially paramount in the public sector. For reasons aforementioned, this was not fully realized with the Dome, and that had no small impact on its image.

True for every space, but especially paramount in the public sector. For reasons aforementioned, this was not fully realized with the Dome, and that had no small impact on its image.

#4: Choose a mission and stick to it.

The Dome tried to please everybody and pleased nobody in the process. This is due to its staggering ambition, outgrowing both its public and private shoes. High-level concepts like "One amazing day" can only carry a project so far.

The Dome tried to please everybody and pleased nobody in the process. This is due to its staggering ambition, outgrowing both its public and private shoes. High-level concepts like "One amazing day" can only carry a project so far.

Global capitalism has long abandoned the idea of building things like World& #39;s Fairs and expos, and even the theme parks we have now are steadily becoming far more driven by their bottom line. It may be the case that the future of artificial spaces lies in public funding.

With that in mind, I think it& #39;s important to revisit projects like the Dome - to learn what went wrong, what almost went right, and how the latter can shape what we build in the future.

We& #39;ve got a lot of time left in this millennium to build cool shit in. We ought to do it.

We& #39;ve got a lot of time left in this millennium to build cool shit in. We ought to do it.

This thread was the product of almost 3 months of spare-time research, far more than any of my previous threads. However, I wanted to see this one through for the hell of it. If you like what you see, give me a follow. I& #39;m making a game, @CROSSNIQ+, that& #39;s pretty cool too.

And, as always, as a reward for those who read to the end - time for video content!

"One Amazing Day" Millennium Dome advert, 1999. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzJWngmDUvQ">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

"One Amazing Day" Millennium Dome advert, 1999. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzJWngmDUvQ">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

A 7-minute promo video, likely sent to schools, put together by the NMEC during the dome& #39;s construction. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgmQJfDkYCA">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Apparently, the NMEC thought the best way to counter poor public opinion of the dome was to run an ad making fun of people who were skeptical of it. Way to win em over. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TkhjKF2nDgg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

One last advert, one that would put the ad agency behind the PS3 baby to shame. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fVAYjXvAUU">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

the best quality recording of the Millennium Show that I could find. Goes pretty much cover to cover! Much of Peter Gabriel& #39;s album seems to go unused in the actual production, sadly. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qe5EVP_048o">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

And finally, the most comprehensive video tour of the dome I could find (though shot through a wide-angle lens). Shows a lot of content I wasn& #39;t able to find pictures of. Enjoy!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jga_J2dIQd0">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jga_J2dIQd0">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

with that, the tale of the dome comes to a close!

woah. it& #39;s almost 4 am here. this thread took about 14 hours. better https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💭" title="Gedankenblase" aria-label="Emoji: Gedankenblase">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💭" title="Gedankenblase" aria-label="Emoji: Gedankenblase"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💤" title="Schlafsymbol" aria-label="Emoji: Schlafsymbol">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💤" title="Schlafsymbol" aria-label="Emoji: Schlafsymbol">

woah. it& #39;s almost 4 am here. this thread took about 14 hours. better

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter