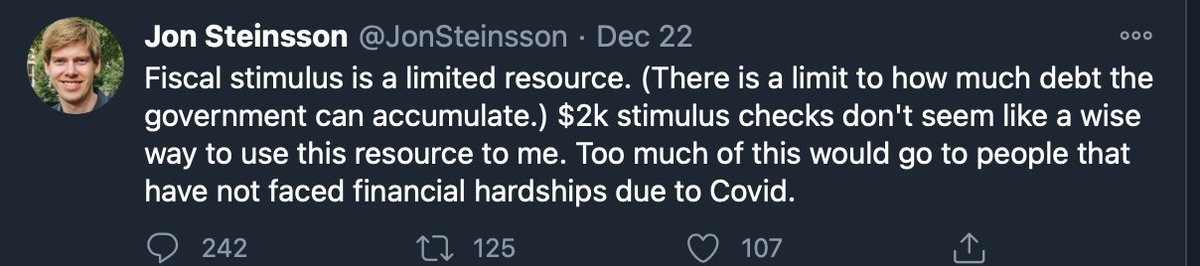

This tweet got "ratioed" (screenshot for reply count), though not as badly as Larry Summers!

I get it, tensions are high. But we should try to have useful conversations, not piling on.

Just a few thoughts.

I get it, tensions are high. But we should try to have useful conversations, not piling on.

Just a few thoughts.

To me, targeting is preferable but if impractical or politically infeasible $600-$2000 seems a reasonable policy for unprecedented times.

But I could be wrong! We should talk about it, think out costs vs benefits, and provide a framework to help determine when it's good policy.

But I could be wrong! We should talk about it, think out costs vs benefits, and provide a framework to help determine when it's good policy.

In my view, relief and stimulus go hand in hand (as I have articulated in work with @VeronicaGuerri7 et al). Relief can help those that need it AND provide the stimulus that does not aim for spending at or above pre-pandemic levels.

By providing relief, we provide needed liquidity. Governments providing liquidity in various ways during exceptionally dire times is a time-tested idea, both central banks and treasuries. Best to err on the side of providing extra liquidity, than fall short.

In this way, the argument against checks based on the idea that we do not want to stimulate during a pandemic misses the point.

Stimulating via relief does not immediately imply overstimulation.

Stimulating via relief does not immediately imply overstimulation.

If some people largely save it, okay, they will not stimulate.

But some won't save it and are constrained by their current cash and we wanted to get to them. If this is the only way to do so, we cannot dismiss it so easily I think.

But some won't save it and are constrained by their current cash and we wanted to get to them. If this is the only way to do so, we cannot dismiss it so easily I think.

Now, what are the arguments against this?

One principle is that a higher deficit and debt will require higher taxes in the future (putting r < g arbitrages aside). This may be inefficient or not credible. Lack of credibility should show in the bond market, but hasn't.

One principle is that a higher deficit and debt will require higher taxes in the future (putting r < g arbitrages aside). This may be inefficient or not credible. Lack of credibility should show in the bond market, but hasn't.

But it's okay to ask if this could push us closer to a credibility/debt problem. That's one way to take Jon's question. I do not think so. If anything I'm more worried about perennial deficits during normal times than these efforts during crises.

But I think it's fair to ask this question and try to make quantitative stabs at it.

As for the efficiency question, a venerated principle of Public Finance is tax smoothing: we should avoid having higher taxes in future than today, better to equate them.

As for the efficiency question, a venerated principle of Public Finance is tax smoothing: we should avoid having higher taxes in future than today, better to equate them.

An important principle to be sure (which we probably already violate during normal times!) but derived under standard neoclassical assumptions, not situations where governments can help by providing extra liquidity/relief during crises.

In sum, I just do not see a clear argument against checks as a countercyclical fiscal policy, during these times, as a matter of principle.

But I can also see that there is enough we do not know for reasonable people to disagree on a quantitative conclusion.

But I can also see that there is enough we do not know for reasonable people to disagree on a quantitative conclusion.

Suppose Jon had instead written:

"You think $2000 checks is a good policy, maybe you ar right. But where to stop? What about $4000? $10k? $50k?"

Pushing the question, it's clear we do need to sharpen our answers and think about possible tradeoffs at some point.

"You think $2000 checks is a good policy, maybe you ar right. But where to stop? What about $4000? $10k? $50k?"

Pushing the question, it's clear we do need to sharpen our answers and think about possible tradeoffs at some point.

In short, wherever you land on this, no need to be dismissive. Not all those arguing for these payments are ignoring borrowing constraints, or those arguing against heartless or illiterate fiscal haws. We can try to think harder about these questions.

cc @JonSteinsson

cc @JonSteinsson

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter